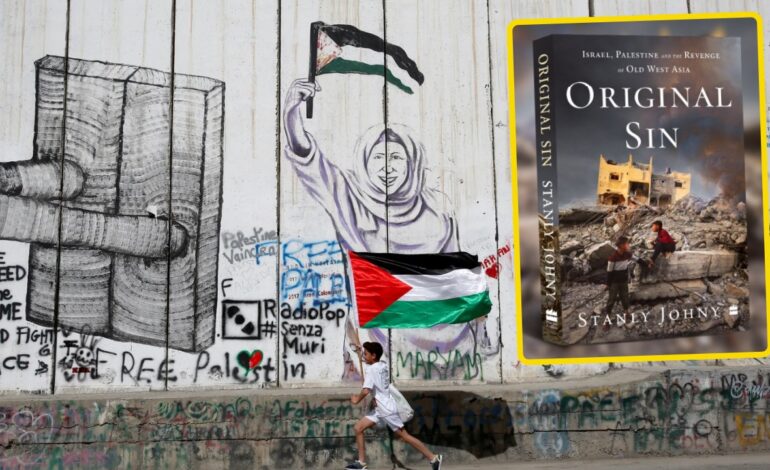

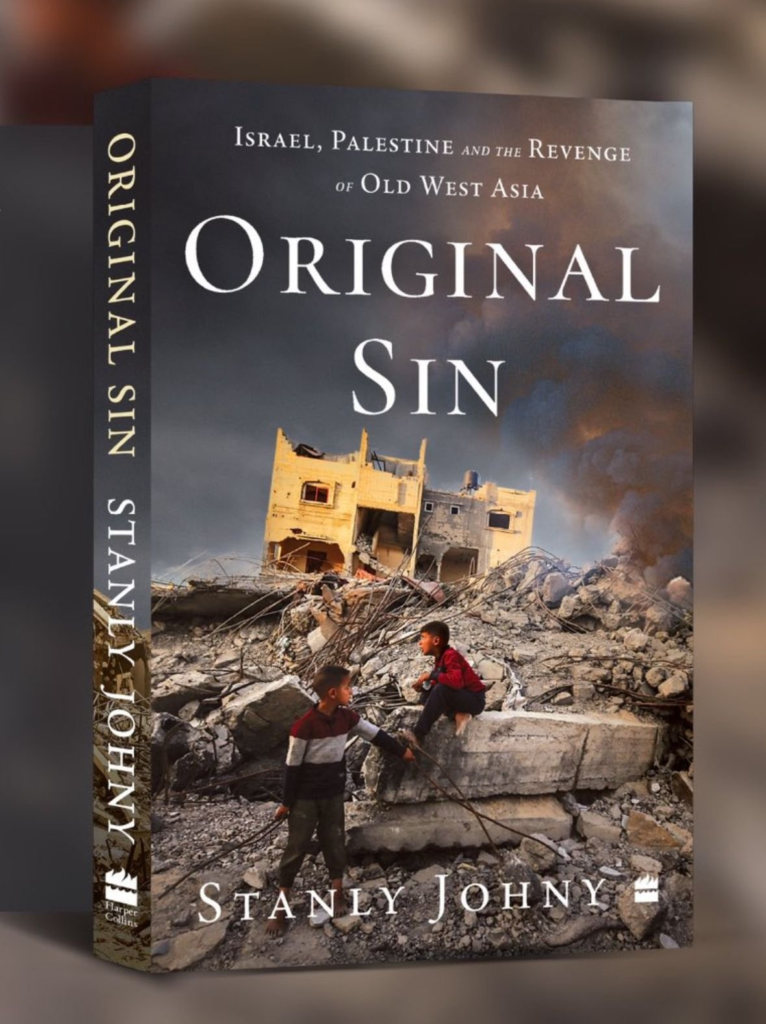

Original Sin: Israel, Palestine, And the Revenge of Old West Asia

Stanly Johny’s latest book, Original Sin: Israel, Palestine, and the Revenge of Old West Asia is an in-depth analysis of the most pressing geopolitical conflicts of our times. Beyond the confines of a traditional history book or an explainer, it offers a nuanced understanding of the Israel-Palestine conflict within West Asia’s larger civilisational complexities. Stanly’s treatise gives both context and perspective to fathom the conflicting narratives that flood our newsrooms, especially after the October 07, 2023 attack by Hamas on Israeli soil and the cataclysmic assault on Gaza that resulted in the killing of over 46000 Palestinians and near obliteration of Gaza.

Hamas’ attack on Israel

In the introduction to the book Stanly writes: ‘“I was shocked by the brutality of the Hamas attack but not surprised by the attack itself.” This statement sums up the central argument of the book, that the cycle of violence and terror engulfing the region is intrinsically linked to the historical injustices, particularly the Nakba of 1948, where over 7,00,000 Palestinians were uprooted to create the state of Israel. Stanly considers the October 07 attack on Israel by Hamas as a watershed moment in the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Yet, he refuses to portray it as an isolated eruption of violence that is alien to the region. Instead, he positions the deadly hostilities as an important episode in the century-long tale of imperial drive, dispossession and resistance, explains its political and diplomatic ramifications and encapsulates what he terms as ‘revenge of Old West Asia’.

A Passage to West Asia

Stanly’s ability to weave personal accounts with scholarly assessment is evident in the book’s third chapter titled ‘A Passage to West Asia’. Here, he chronicles his many visits to Palestinian territories, with an incisive analysis of present-day Palestine and the heartrending realities of life under occupation.

In one particularly moving incident, he recalls an interaction with an official named Georgy in the West Bank. As they shake hands, Georgy asks the author, “How’s Palestine, my friend?” When Stanly replies, “It’s good,” the official sharply retorts, “It’s not good.” This exchange captures the hopelessness that characterizes modern-day Palestine.

The entire region is under Israeli military occupation. The Palestinian Authority has less power than a municipality in India. Stanly also describes the psychological and physical wounds of a region torn apart by illegal settlements, apartheid fences, and relentless military assaults.

What makes Original Sin unique is Stanly’s on-the-ground reporting, which graphically portrays the realities of occupation and resistance. He details the oppressive apartheid wall, the daily humiliations faced at Israeli checkpoints, and the resilience of Palestinians who refuse to abandon their ancestral lands despite overwhelming challenges.

The book provides a comprehensive account of the voices of native people affected by the conflict. Stanly shares his experiences with a shopkeeper in Ramallah, a university student from the West Bank, and a Christian Palestinian residing in Bethlehem, not as mere footnotes in the narrative; but as central characters whose experiences highlight the human cost of occupation and war.

Their stories are linked with Israeli policies, including settlements and the systematic erasure of Palestinian history and culture. He explores the fate of the holy city of Jerusalem, connecting its significance to the three Abrahamic faiths. Adinah, a university student whom the author meets in Jerusalem, reflects on both the charm and tragedy of the city, as well as the perceived helplessness of Gods in Jerusalem.

In an era of polarised commentaries, “Original Sin” distinguishes itself through its commitment to nuance. Stanly refuses to simplify the conflict into simple binaries. Instead, he takes the readers through the foundational violence of the Israeli state, the complicity of Western powers, and the enduring resilience of the Palestinian people. He also traces the history of Hamas and explains how it evolved from the Israel-funded Islamic Cultural Centre and the Muslim Brotherhood. The author is critical of Hamas’s tactics, yet refrains from labelling it a terrorist organisation because Israel commits even more brutal acts of violence against Palestinians.

Another important feature of the book could be seen in its coverage of the October 07 attack on Israel. Stanly’s genuine sympathy for the Palestinian cause does not prevent him from giving voice to the legitimate fears of Israeli civilians. His narration of the October 2023 attack by Hamas from the perspective of a Canadian-Israeli peace activist, Vivian, who was ultimately killed in the attack, is a testament to this non-partisan approach. However, the author is aware of the asymmetry of power between a powerful occupying state and a stateless people fighting for survival.

Geopolitics and the Revenge of Old West Asia

Stanly articulates the geopolitics of West Asia with clarity and conviction. He dissects the international alliances and peace talks in the region and the roles of Iran, Hezbollah, and other actors within the “Axis of Resistance.” He exposes the cynical strategy by the United States and Israel to sideline the Palestinian issue while normalising relations with authoritarian Arab regimes. Additionally, he elaborates on how Iran has evolved into a strategic force throughout West Asia like a strategic octopus.

Stanly’s cogent summation of intertwined forces of colonialism and geopolitical relations places the Palestine question in the broader dynamics of Old West Asia. The contributions of European anti-Semitism, the pogroms in Tsarist Russia, and the horrors of the Holocaust towards the emergence of Zionism is documented. The author assiduously elucidates how Britain and later the Americans sowed seeds of violence in the region. The establishment of Israel in 1948, Stanly argues, was not only the culmination of Zionist aspirations but also a project facilitated by Western imperialism, executed at the expense of the Palestinian people.

Beyond the pointed narration and analysis of the past, the book frames the ongoing violence as the “revenge of Old West Asia,” highlighting how the region’s suppressed voices—its displaced peoples, insurgent movements, and resistance networks—continue to challenge the power structures imposed by imperialism and settler colonialism.

India’s perceived shift in its policy towards Israel also forms a part of the narrative. India has been a staunch supporter of the Palestinian cause from colonial times to date. The difference in opinion between the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of External Affairs is explained as well. The author views this shift as part of broader global trends, where countries increasingly prioritise strategic alliances over ethical considerations. “Original Sin” is a crucial read for in-depth understanding of the Israel-Palestine conflict.