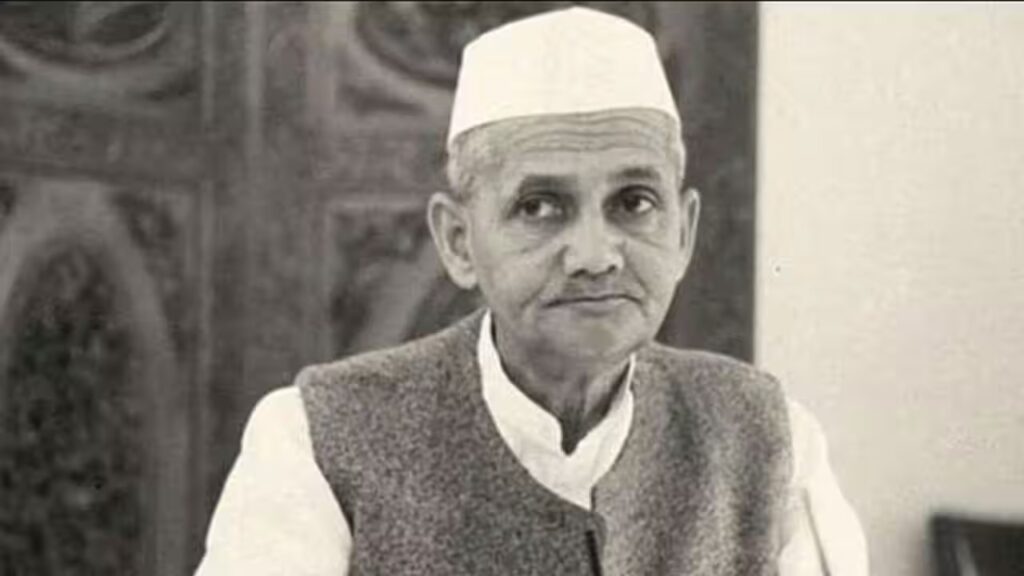

Lal Bahadur Shastri: A Politician of Substance

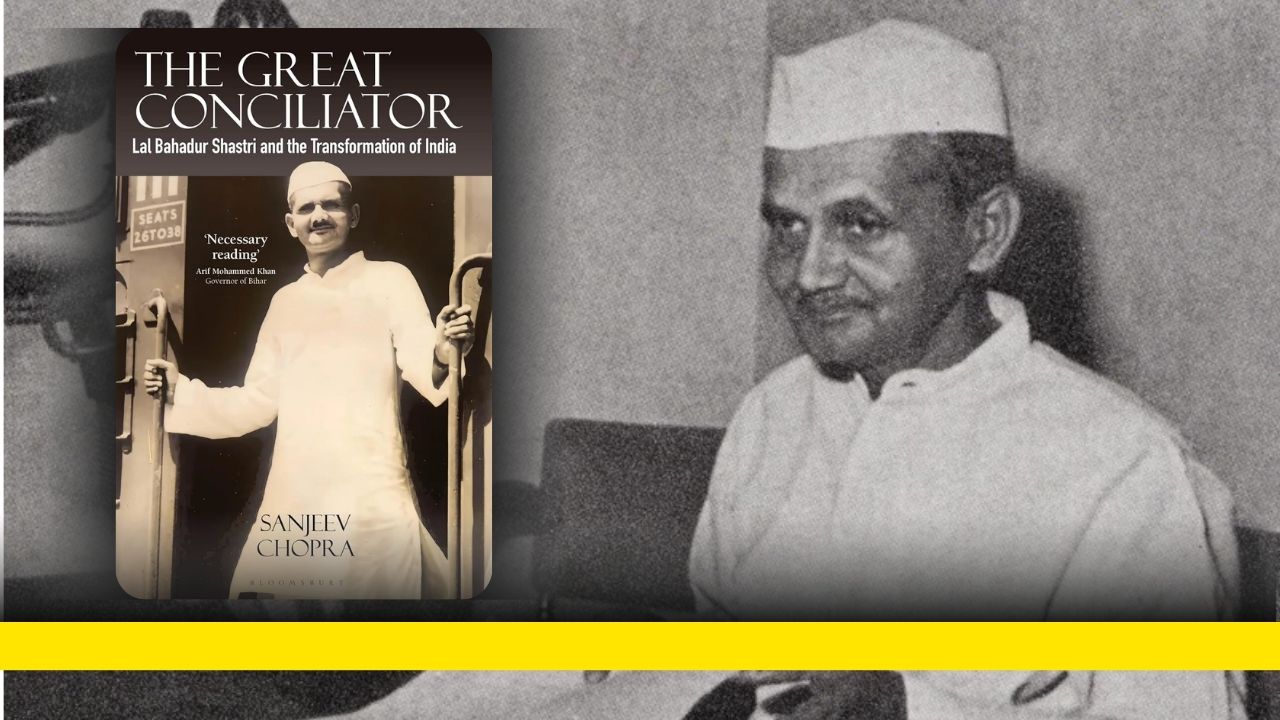

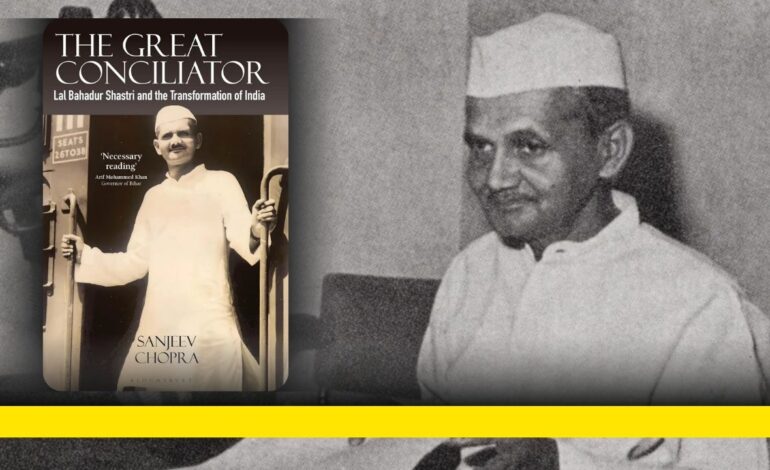

In the grand gallery of Indian political history, Lal Bahadur Shastri often remains a quiet portrait – respected, but rarely studied with the depth he deserves. Overshadowed by towering figures like Nehru and Indira, Shastri’s legacy has long awaited a lens that doesn’t just recount his humility, but explores the sharp political instincts behind that modest exterior. “The Great Conciliator: Lal Bahadur Shastri and The Transformation of India” by Sanjeev Chopra attempts exactly that – offering not just a biography, but a deliberate act of reclamation. It steps into the silences around Shastri, asking: What kind of strength does it take to lead a nation with quiet resolve? Arvindar Singh investigates in his latest book review.

Lal Bahadur Shastri was the second Prime Minister of India who held the office for 19 months from June 1964 to January 1966. As is well known his tenure was cut short by his untimely death at Tashkent where he had gone for peace talks with Pakistan in the wake of the 1965 war . The peace talks had taken place at the mediation of the erstwhile Soviet Union.

This book, written by a former Bureaucrat Sanjeev Chopra who is a prolific writer and curates the highly successful Valley of Words Literature Festival annually at Dehradun, fills up a long standing requisite of an all-inclusive life story of Shastri. Although some works have already been published by those who personally knew and worked with India’s second Prime Minister, this book stands apart as the amount of flawless research which has gone into it is indeed commendable. However, it must be stated that it is a hagiography for which the author has made no effort to hide as he clearly represents the viewpoint of Lal Bahadur Shastri.

Shastri rose from the ranks and from humble beginnings was able to get higher education at the Kashi Vidyapeeth of Varanasi before plunging into the humdrum of active politics. In 1936 Shastri was elected President of the Allahabad District Congress Committee and a member of the Allahabad Municipal Board.

Being the only person in the Municipal Board who knew the real suffering of the masses, having himself come from a economically weak background he gave emphasis to opening dispensaries and public toilets in the areas where the less prosperous persons of the town resided. He proposed among other things that no employee of the Municipality should be paid more than five hundred rupees per month.

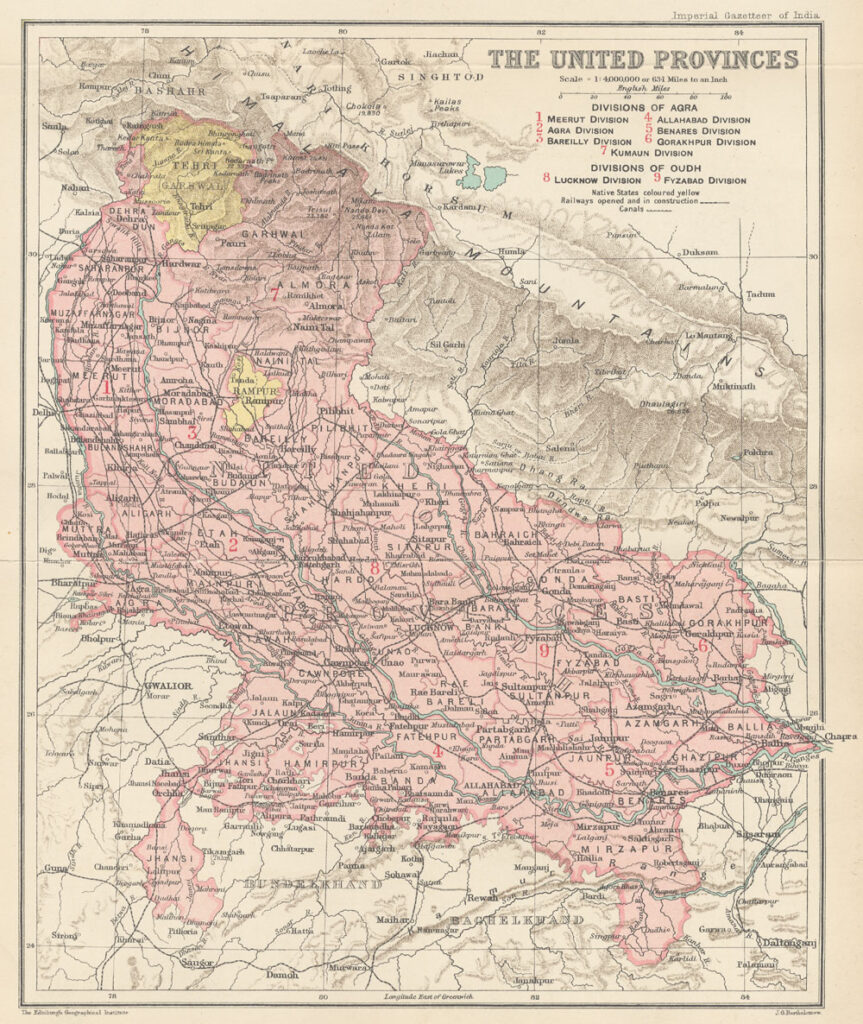

By a quirk of fate being a shadow or dummy candidate in the Assembly Elections of 1937 held under the Government of India Act, 1935 catapulted him into the Legislature of the United Provinces (as Uttar Pradesh was then known). The candidature of the formal Congress candidate was rejected and thus Shastri fought the election and won.

As a legislator during this period Shastri took part in debates on agrarian reform and was instrumental in bringing about relief to small farmers and poor tenants through his active participation in the United Provinces Agriculturists Relief (Amendment) Bill, 1937 and other bills on the same subject like the United Provinces Stay of Proceedings (Revenue Courts) Bill of 1938, Chopra records.

After Independence Shastri occupied a ministerial post in Uttar Pradesh and was General Secretary of the Congress later in Delhi. Post the first general election Shastri joined the Union Cabinet as Minister for Railways and Transport. The book gives glimpses of his various Railway Budget speeches during the period he held charge of the ministry which gives a glance of his priorities in this department. He took concrete steps to improve the lot of the travelling masses in the Third Class section of the Railways, showing his understanding of their needs.

Shastri was also Communications and Commerce and Industry Minister as well as Minister for Home Affairs after the demise of Govind Ballabh Pant. The book well covers his role during the Sino-Indian conflict of 1962, as the Defence Minister Krishna Menon was increasingly under fire and ultimately had to quit his office, Shastri acted as Nehru`s main points-man during the crisis.

The most interesting part of the book concerns the events leading up to Shastri`s assumption of the Prime Ministership and his tenure in office. The aftermath of the Chinese aggression resulted in a period when the image of the Nehru government took a beating. By July-August 1963 the Kamaraj Plan was being discussed under which it was decided by the AICC that senior Ministers of the central cabinet and some Chief Ministers would quit to work for the party.

Here Shastri had a role which although not covered in the book could border on the diabolical. Morarji Desai, the then Finance Minister has said the following in his autobiography about the time the Kamaraj Plan was being discussed, “ Two days before the Working Committee meeting, Lal Bahadur Shastri told me when he met me in the lobby of the Lok Sabha that he had pressed for his resignation to be accepted and he would give up office but it was not necessary for me to give up office…….When he spoke to me in this manner, I suspected some game was being played behind the scenes.” (Morarji Desai, The Story Of My Life, Vol. II, Page 200, Macmillan India, 1974).

Nehru passed away on 27 May 1964. By now Morarji was out of the cabinet under the Kamaraj Plan, so had been Shastri but he had rejoined the government after Nehru suffered a stroke in January 1964 . Shastri was then appointed as Minister Without Portfolio. In the run-up to succession the two contenders for the Prime Minister’s post were Morarji Desai and Shastri . In a probable media plant Desai was portrayed as over ambitious, and the requirement of unanimity so soon after the death of Nehru resulted in him (Desai) withdrawing from the race.

Though not mentioned in the volume Shastri attempted to take Desai in his cabinet but by offering him the number three position after Gulzarilal Nanda who had been the acting Prime Minister before his own elevation . Shastri created a position where Desai (who had been number two in Nehru’s cabinet) had no choice but to refuse. Was there a manoeuver in this as well? Desai`s autobiography gives this impression as he felt Shastri was not above double dealing on the political front. Some mention of a few such negative aspects of his personality would have added value to the book.

The 1965 War is well covered in the book as well as Shastri`s forays in laying firm foundations in the Green and White Revolutions. C. Subramaniam and Vargheese Kurien did exemplary work in this direction. Indira Gandhi and Jagjivan Ram – Prime Minister and Agriculture Minister in the subsequent government – also have a major role in the implementation of both the Green and White revolutions.

The 1965 war was undoubtedly Shastri`s finest hour and we were militarily successful in Hajipir, Tithwal and on the Lahore front. However, the agreement to the UN sponsored cease fire at that particular time is controversial. The late Marshal of the Air Force Arjan Singh (who was Chief of Air Staff during the war) had in an interview with me (Defence Watch, April 2002) mentioned that it was agreed to at a time when the Air Force and the Army were hitting their stride and had the war gone on a little longer the outcome would have probably been much more decisive. This view was echoed by Captain Amarinder Singh a 1965 war veteran and former Chief Minister of Punjab in a Q&A interaction I had with him at a book launch a few years back.

The Tashkent Agreement was the outcome but sadly Shastri did not come back alive. Had he lived certainly there would have been much more integrity in public life as he was financially above board. In a nutshell , this book is an important addition to the library of biographies of our former Prime Ministers.