India has not elected Narendra Modi just once, but three times consecutively with full parliamentary majority, an extraordinary democratic mandate. These victories were not simply electoral triumphs; they reflected a deep well of weary hope among the public that real change was finally coming. Upon assuming office in 2014, Modi promised that India would no longer pause, but surge ahead. And for a moment, the country did seem ready to run. But 11 years later, many Indians appear either exhausted or fearful.

Though development was heavily promoted through government campaigns, real improvements on the ground have often fallen short. In rural areas, for example, the widely publicised Ujjwala scheme provided millions of poor families with subsidised cooking gas cylinders. However, many households used them only a few times before abandoning them, unable to afford refills. In 2023-24 alone, millions did not refill their cylinders.

India’s farmers continue to struggle. Although subsidised food rations are available, the prices farmers receive for their produce often fail to cover even basic household expenses. Urban healthcare tells a similar story: while hospitals exist, government health centers remain chronically understaffed, and private healthcare remains prohibitively expensive for a large segment of the population.

In education, while funding and policy frameworks exist, thousands of teaching positions remain vacant for years. Increasingly, students are discouraged from asking questions. Debates that were once seen as part of academic discourse are now viewed with suspicion, even as acts of subversion.

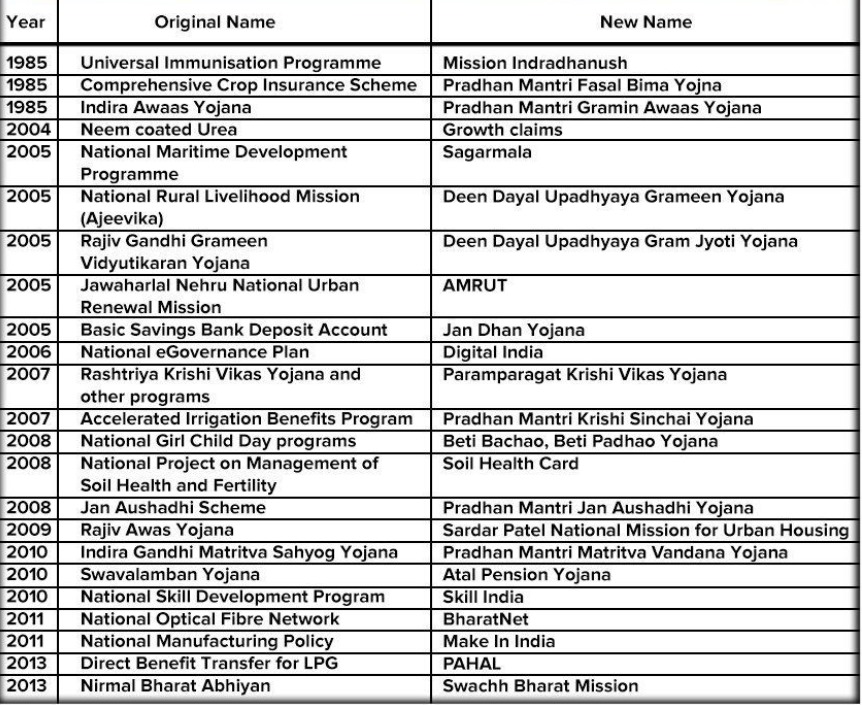

The Modi government introduced high-profile campaigns such as Digital India, Make in India, and Startup India to project an image of modernisation and growth. Yet, by 2024, India’s manufacturing sector contributed only 14.6% to the country’s GDP a decline from 15.1% in 2014 when Modi first took office. Data from India’s Employees’ Provident Fund Organization (EPFO) shows that the vast majority of new jobs offer salaries of less than ₹15,000 (about \$180 USD) per month.

Alongside economic uncertainty, political terror has also grown. Students who protest risk being charged under draconian laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and sedition statutes. Journalists face frequent raids by tax authorities and financial enforcement agencies. Opposition politicians often find themselves either imprisoned or entangled in lengthy investigations by federal agencies such as the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

The space for democratic debate has shrunk significantly. Parliament, once the heart of India’s democratic process, now sees little genuine discussion. In the winter session of 2023, 141 Members of Parliament were suspended, creating the sense that democracy itself had been paused.

This raises a critical question: which direction is India headed? To search for answers, many Indians are revisiting an earlier chapter in the country’s history the era of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister.

Today, Nehru is one of the most heavily criticised figures in modern Indian political discourse. Yet, he maintained an open atmosphere for dissent. Opposition leaders had a voice in Parliament among them, socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia, who relentlessly criticised Nehru without ever being silenced. The press operated freely, even when slogans like “Remove Nehru” gained popularity Nehru never deployed investigative agencies against his critics.

Instead, Nehru focused on building India’s institutional foundation. He established premier institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), University Grants Commission (UGC), and Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR). These institutions remain pillars of India’s growth to this day.

Nehru understood that nation-building is not solely about territory or military strength, but about nurturing ideas. He promoted scientific temper, enshrined secularism in the Indian Constitution, and upheld constitutional democracy even during periods of extreme challenge.

Under his leadership, democracy was treated as a lived practice, not just a procedural exercise. Elections were opportunities for accountability, not just for victory. In Nehru’s time, India’s per capita annual income was barely ₹250 (around \$3 USD at historical rates), yet his government invested in scientific research, nuclear energy, irrigation projects, and transformative public works like the Bhakra Dam all while encouraging critical thinking as a public virtue.

By contrast, in today’s India, opposition leaders who question the government often face legal action or are labeled “anti-national.” Many significant decisions are announced via television broadcasts rather than after parliamentary debate and scrutiny.

Criticising Nehru remains important and legitimate but such criticism should serve as a means of reflection, not personal vendetta. Nehru allowed room for dissent, fostered debate in Parliament, and practiced democracy as a cultural value. Under Modi, Parliament has increasingly become a site for the swift passage of legislation rather than deliberative debate, more a stage for declarations than for democratic discourse.

This distinction is critical. Modi possessed a historic opportunity, an unprecedented mandate, and immense power. He could have steered India not just toward a Hindu-majority state in spirit, but toward an inclusive republic in reality. Like Nehru, he could have fortified India’s core values of scientific inquiry, education, and democratic pluralism. Instead, he chose the path of emotional appeals, propaganda, and centralised control.

When Nehru left office, it wasn’t because he was overthrown; he willingly accepted the democratic process of political transition. He cultivated a political culture where electoral defeat was not viewed as humiliation, but as part of democracy itself.

History will undoubtedly remember Narendra Modi as a formidable communicator, and an unmatched electoral strategist. But will he be remembered as a nation-builder as Nehru is?

Nehru’s legacy was not limited to the institutions he built, but also included the practice of freedom itself. Modi’s legacy involves not just his electoral majorities, but his attempt to consolidate control over an entire ideological spectrum.

Nations are not built by leaders alone; they are built by ideas. And ideas flourish only in spaces free from fear where criticism is permitted, even welcomed.

Nehru created such a space. Modi has moved away from it.