As India’s most contentious election comes to a close, journalist Revati Laul went down to the city of Varanasi where Prime Minister Modi is hoping to score a third landslide victory. She found however that even in this BJP bastion, there is considerable dissent.

There’s always a to and fro, an uneasy stutter, a flicker before a change of scene. The end of a romance, an empire, an era. Was this all there was? Will this be there tomorrow? It is only then, after that last conversation, that the curtain lifts on a dark stage, the moon goes out to dinner and an uncertain sky moves from dark to light, with that purple uncertainty between tonight and tomorrow.

We are in that last conversation in India, before the lights go out on this election and a verdict comes in. And the last wisps are heard as a cascade of things been blown east, towards the ghats of Varanasi, where souls are cremated and people say their last goodbyes, releasing energy, toxic and good, as ash, into the river Ganga that has been swallowing civilizations and ideas for thousands of years. It is now preparing for another such interlude. I was there to listen for one thing in particular. I didn’t come here for balance, to try and ask fifty people five questions and then gauge what will come next. I wanted to put my ear to the ground where Prime Minister Modi is contesting for a third time in office, listening for only one sound – possible dissent.

They say this is not the way to write about an election. If you go looking for something you will of course find it, and then what of it? How will it tell us anything about anything? I had a counter. In an election where the country seems poised between democracy and possible dictatorship, where the polarising is so extreme and the country is in collective anxiety, it seemed as if the regime in power had orchestrated most mainstream sound one way, its way. So altering the balance might require listening for voices from the street that might not please Mr. Modi and seeing if these voices could possibly come even from the ruling party’s most bankable constituency – Modi’s own.

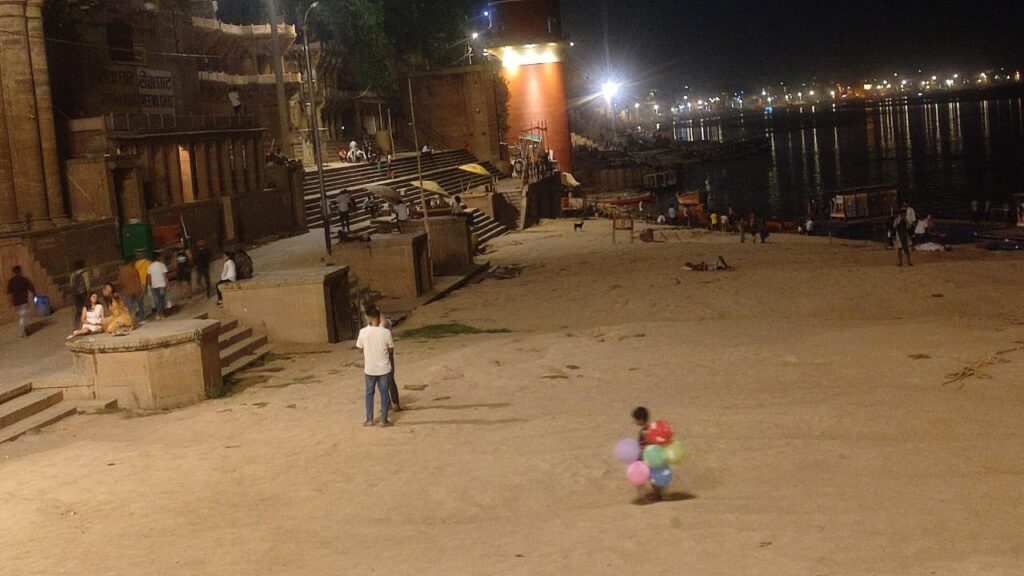

The stage was set. Or rather the un-stage. I wanted to close in on the un-scene after the evening aarti was done at the Assi Ghat. The last shop was closing. The last balloon-seller child on stick-figure emaciated legs bounced off stage, out of the ghat, to the gully behind, with the five remaining globular pink lollipop-like balloons. The boats formed grey teeth at the far end of the river.

Three art students were looking for models to practise their sketches, to make up the portfolio for their degree. “If this election is fair and there isn’t cheating in the EVMs or voting machines, Modi could lose a lot of votes even here, in his constituency,” said one. “He just waltzes in here and does whatever he likes, he needs to be shaken up, even if it means shaving off a few thousand votes,” said another and he explained. “He came to the Assi Ghat the other day and said this road needs to be widened and then he sent off an order to that effect and this now means some of those street vendors will be made to go. Where will they go?”

A street vendor listening to the art students chipped in. “There is an 18% GST tax on Education. If education and food can’t be made affordable, what is the point of anything, that’s what he’s done.”

I needed to do a quick round of who’s who – from what community, to find out if this conversation was limited to a particular caste or community that has generally been dissenting. “I’m OBC Saini, I’m Maurya, I’m Brahmin, I’m from the SC – I’m Rao.” The four people in conversation were from castes normally seen as voting firmly for Modi like the upper caste brahmin and the OBC Saini and Maurya students.

Another young boy decided to chip in here. “I don’t care about any election, everyone is somebody’s puppet – this regime or the other…everyone is colluding with everybody…Indira Gandhi was assassinated, what happened to Nehru, and now the Iranian President has died, how can we be certain it was an accident, how can we be certain of anything? There are conspiracies everywhere.”

Earlier in the day, at a more predictable place for dissent, I listened to what people said as they exited a big, fat Opposition Rally with the Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Yadav and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi speaking.

“Change, there will be a regime change,” said some, emerging animated as flags were being rolled up and dust flew everywhere. “We’ve had enough of unemployment and skyrocketing prices,” said another. “That’s why we have to shake things up, even here, where Modi is contesting.”

“He’s scared, that much I’m certain of,” said another who did not want to be identified because he has a government job. When I asked how he could be so certain, this was his reply. “For an ordinary power outage, which happens every summer, it’s 48 degrees, a man was sacked from his job and I read that even the Union Power Minister got involved. And the whole Union Cabinet is here, that’s how I know he’s scared.” I didn’t want this to be about facts – was the Union Cabinet in Varanasi? I was recording perceptions.

I asked once again, for people in conversation, to tell me their castes. “There is an assumption that political watchers have made. Upper-caste and many OBCs have been loyal to Mr. Modi,” I said, spooning in an ingredient into the dialogue in progress. “Therefore, tell me what communities you come from.”

“We’re a mix here – Brahmin – Sharma and Seth, OBC – Vishwakarma, Yadav, Muslim OBC – Ansari…” Two Beat constables had relaxed because the crowds had thinned, so they joined in. “There will most likely be a regime change, we can sense it,” they said, their eyes shining bright.

A woman emerged from amongst the crowd, accompanied by a male relative. I asked her what she had heard at the opposition rally and what she liked. “If the regime changes, there will be 8,500 given to women in our accounts, ‘taka-tak-taka-tak,’ she said, quoting from Rahul Gandhi’s campaign speech.

It was hot, the night was upon us and the Ghat was grinning itself to sleep, the last lights slowly fading out on the horizon. Dissent was clearly not the only conversation the river carried with it. It may not even be the most significant.

That enough of it was out and about Varanasi, in places it ought not to be may not cause Prime Minister Modi to exit stage as it were, or for there to be a new play in town. But its presence has given this election a decidedly Shakespearean ring. Macbeth, eyes green and heavy with indecision as he ascends the stairs, preparing to kill King Duncan. As he prepares his knife, he sees ghosts, he talks to himself, should he ascend the stairs?

The Ghats are bewitching when the aarti is done and no one is watching. The garbage is piled up on one side, to be removed in the morning, along with the stars and the lights and the Moon. A few people have propped up their wasting away bodies against gunny sacks and after the day’s begging, are preparing to sleep. Nobody knows what’s coming next.

Photographs taken at Assi Ghat, Varanasi by Revati Laul.