As Aurangzeb Becomes A Point of Discussion Again

First, a disclaimer. Emperor Aurangzeb was not my great-great uncle. Nor is Maharashtra Samajwadi Party MLA Abu Asim Azmi my cousin. I have no reason to defend either. But what compels me to write this piece are the agonising details of a controversy in Maharashtra, where some people are baying for Azmi’s blood.

The MLA has already been suspended for the remainder of the ongoing session of the Maharashtra Assembly. Some leaders want the Assembly to expel him from the House. One even wants to bar him from contesting elections in the future.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath wants Azmi to be sent to his state, where he knows how to “handle” people like him. A day after this, the Education Minister in Rajasthan used the Assembly to call Akbar the Great a “rapist.” He used many other derogatory words for the Emperor, whose name he wants erased from history.

What is amusing is that this discussion revolves around two individuals who ruled the country more than 300 years ago. Three years ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi waxed eloquent when India surpassed Britain to become the world’s fifth-largest economy. He gave the achievement a political twist by adding that India had “left behind those who ruled India for 250 years.”

I don’t think China, whose condition in 1947 was similar to India’s when it gained independence, made such boastful claims when it became the world’s second-largest economy, replacing Japan. It could have pointed out that it was the same Japan that had tried to annex large parts of China in the early 20th century.

Modi’s statement amused me because Sanjiv Mehta, an India-born British businessman, purchased the East India Company, which came to trade with India about 300 years ago and went on to rule the country for nearly 200 years. It was the world’s first multinational company. Mehta said at the time, “I had this huge feeling of redemption—this indescribable feeling of owning a company that once owned us.”

I don’t know how ecstatic Modi would be if India beats China and the USA to become the world’s largest and first quadrillion-dollar economy. For context, the world’s total GDP is currently only $120 trillion. Let Modi accomplish this seemingly impossible task!

You may accuse me of going bonkers with such suggestions. Let me return to the present reality. Just 20 years ago, then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was conferred an honorary degree by Oxford University. While accepting the degree, Singh took a dig at the British. Let me quote his brilliant speech:

“As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India’s share of world income collapsed from 22.6 percent in 1700, almost equal to Europe’s share of 23.3 percent at that time, to as low as 3.8 percent in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, ‘the brightest jewel in the British Crown’ was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.”

Congress leader Shashi Tharoor virtually paraphrased Singh’s statement in his much-celebrated Oxford Union Society address in 2015. Modi was so impressed by his speech that he tweeted it, giving the address a much larger audience than the Congress MP could have imagined.

In other words, Modi accepts the point that India had a better economic condition before the British arrived in Delhi via Surat in Gujarat. Now, let me quote Niall Ferguson, author of “Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World”. As the title suggests, he was an apologist for the British.

“In 1700, the population of India was twenty times that of the United Kingdom. India’s share of world output at that time has been estimated at 24 percent—nearly a quarter; Britain’s share was just 3 percent. The idea that Britain might one day rule India would have struck a visitor to Delhi in the late 17th century as simply preposterous.”

India’s GDP is about $3.8 trillion, while the world’s is roughly $120 trillion. India’s share of global GDP is less than 5 percent. In contrast, India’s share of world output in 1700 was 24 percent, according to Ferguson, and 22.6 percent, according to Dr. Manmohan Singh.

In other words, India was never as rich as it was in 1700. Certainly not during the British period or later under Dr. Manmohan Singh or Narendra Modi. At the current growth rate, it will take centuries, if not millennia, for India to regain the economic clout it had in 1700. Now, who was the ruler of India in 1700, whose achievements should have outweighed his failures?

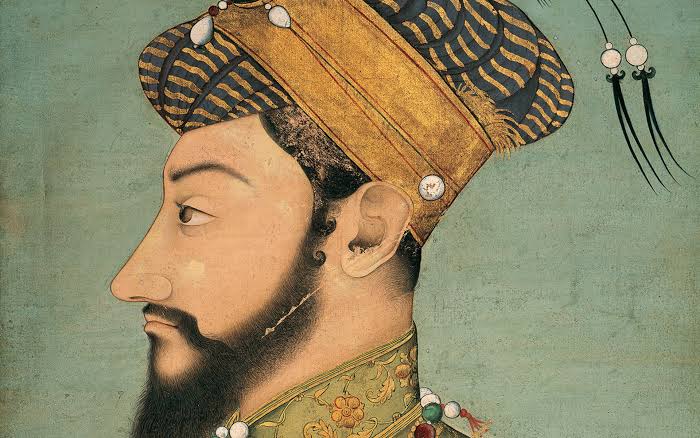

He was Emperor Aurangzeb. He was 88 years old and had ruled the country for 49 years when he died in 1707. Unlike any other leader, he had much to boast about. He ruled “over a population of 150 million people. He expanded the Mughal Empire to its greatest extent, subsuming most of the Indian subcontinent under a single imperial power for the first time in human history.

“He made lasting contributions to the interpretation and exercise of legal codes and was renowned—by people of all backgrounds and religious stripes—for his justice.

“He was quite possibly the richest man of his day and boasted a treasury overflowing with gems, pearls, and gold, including the spectacular Kohinoor diamond,” writes Audrey Truschke, author of “Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth”. Was he a proud and boastful person? The irony is that he was not. His accomplishments failed to assuage his angst about his political deficiencies in his final days.

In fact, as he lay on his deathbed in 1707, “Aurangzeb penned several poignant letters to his sons, voicing his gravest fears, including that God would punish his impiety. But, most of all, he lamented his flaws as a king.

“To his youngest son, Kam Bakhsh, he expressed anxiety that his officers and army would be ill-treated after his death. To his third son, Azam Shah, he admitted deeper doubts: ‘I entirely lacked in rulership and protecting the people. My precious life has passed in vain. God is here, but my dimmed eyes do not see His splendour.”

Aurangzeb was the sixth and final Mughal ruler. He did not want his glory to be exemplified. Far from that, he awaited with bated breath the final day of judgment. He believed he was accountable to the Almighty for everything he did.

He did not want a large tomb built for him. The once-richest man in the world, who ruled a country as large in square kilometres as modern-day India, was buried in a nondescript tomb in Maharashtra, unlike the grand Humayun Tomb in New Delhi that President Barack Obama visited or the grand structure called Akbar’s Tomb in Agra.

It is this man who is hated the most in India today. Why blame the BJP and Shiv Sena members who suspended Azmi from the Maharashtra Assembly? They are all victims of their own propaganda. I saw a video of a few people disfiguring the signboard that says Akbar Road in New Delhi. They made inflammatory statements to be circulated on social media.

A few years ago, Modi used the Red Fort to pour scorn on Aurangzeb. The occasion was the 400th Prakash Purab of Guru Tegh Bahadur. “This Red Fort is a witness that even though Aurangzeb severed many heads, he could not shake our faith.” The political implications of his statement could not have been lost on discerning people. Was he killed because of his religion? How could he have committed genocide against Hindus in an overwhelmingly Hindu nation?

A few years ago, my friend and former IAS officer Amita Paul sent me by email a copy of “Zafarnama”, “perhaps the most famous Sacred Persian Document, or Scripture, in Sikh History.” The Epistle of Victory, as it is called in English, was written by Guru Gobind Singh to Emperor Aurangzeb after losing virtually his entire family at the Emperor’s hands.

“It also shows the Guru’s deep knowledge of the Quran Shareef and Islamic scriptures on the one hand and Persian literature on the other. Even a single reading of the “Zafarnama” resolves the mystery and destroys the myth of the Guru’s battles with the Mughals being ‘anti-Muslim’ or ‘pro-any particular religion.’ The fearless manner in which the Guru challenges the legitimacy of Aurangzeb’s unjust orders and actions, when the Guru’s army had been all but annihilated and Aurangzeb still commanded a formidable army, and was Emperor of Hindustan, while the Guru had been rendered homeless, is remarkable.

“The Guru’s words ring with the power of moral authority and invincible truth against the unjust and oppressive diktats and actions of the Emperor, as He reminds Aurangzeb that he holds power only in the name of the Almighty, and he must dispense justice: in his responsible position, he cannot act according to his own whims and fancies.” I would like everyone to read “Zafarnama”, written when Aurangzeb was in power.

It was, perhaps, “Zafarnama” that induced the fears Aurangzeb nursed as he lay waiting for death in 1707. To his sons, he also “confessed his religious shortcomings and the bitter divine judgment he believed he would soon face. A devout Muslim, he thought that he had ‘chosen isolation from God,’ both in this life and the next. And while he came into the world unburdened, he flinched at the idea of entering the afterlife saddled with the weight of his sins. He ended his final letter with an evocative, lingering flourish, pronouncing his farewell thrice, ‘Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.”

My attempt here is not to justify all of Aurangzeb’s actions but to point out that we should not judge the past by today’s standards. Monogamy is today the norm, but all kings had multiple wives and sired dozens of children. Does that mean they can be described as “rapists” because that is how Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita (BNS) defines rape?

While Azmi could be suspended, will those who bay for his blood ask why, in 1675, John Dryden, then Poet Laureate of England, penned “Aureng-zebe”, a heroic tragedy about the reigning Mughal sovereign? The play explores themes of power, betrayal, and ambition in the Mughal court. Dryden portrays Aurangzeb as a noble yet ruthless ruler, grappling with political intrigue and familial strife.

As can be said about many individuals, past and present, the Emperor was also a bundle of contradictions. He had many great qualities, as he had many bad qualities. Unlike other Mughal rulers, Aurangzeb is the least discussed and studied.

The best course of action is to leave the subject to historians. If Azmi is guilty of praising Aurangzeb, so are Modi, Tharoor, and the late Manmohan Singh, who claimed, albeit indirectly, that India was much better off in 1700 than in 2025. Let us learn from history that what matters to the people is the present and the future, not so much the past. In other words, let history be a guide, not a battleground.

Courtesy: Indian Currents