While the Congress party and Rahul Gandhi may face criticism for failing to secure electoral victories or convert promising positions into tangible results, it cannot be said that they are not making efforts. Following a modest resurgence in the 2024 elections, where Congress nearly doubled its Lok Sabha tally from 55 to 100 seats, the party has been implementing organizational changes aimed at revitalizing its cadre and winning elections. Yet, signs of a genuine revival remain elusive.

Congress has experimented with various strategies to challenge the government. In response to the National Herald case, where the Enforcement Directorate filed charges against Sonia and Rahul Gandhi, the party held press conferences across multiple cities. It also launched a nationwide “Save Constitution” campaign, set to begin in late April. Despite these efforts, none of its initiatives have resonated with the general public or party workers. A recent rally in Buxar, Bihar, led by party President Mallikarjun Kharge, faced ridicule due to the large number of empty seats, prompting the suspension of the newly appointed district president. The question remains: why has the party struggled to garner popular support for initiatives crucial to the public interest?

The Economy of Vote and Social Proof

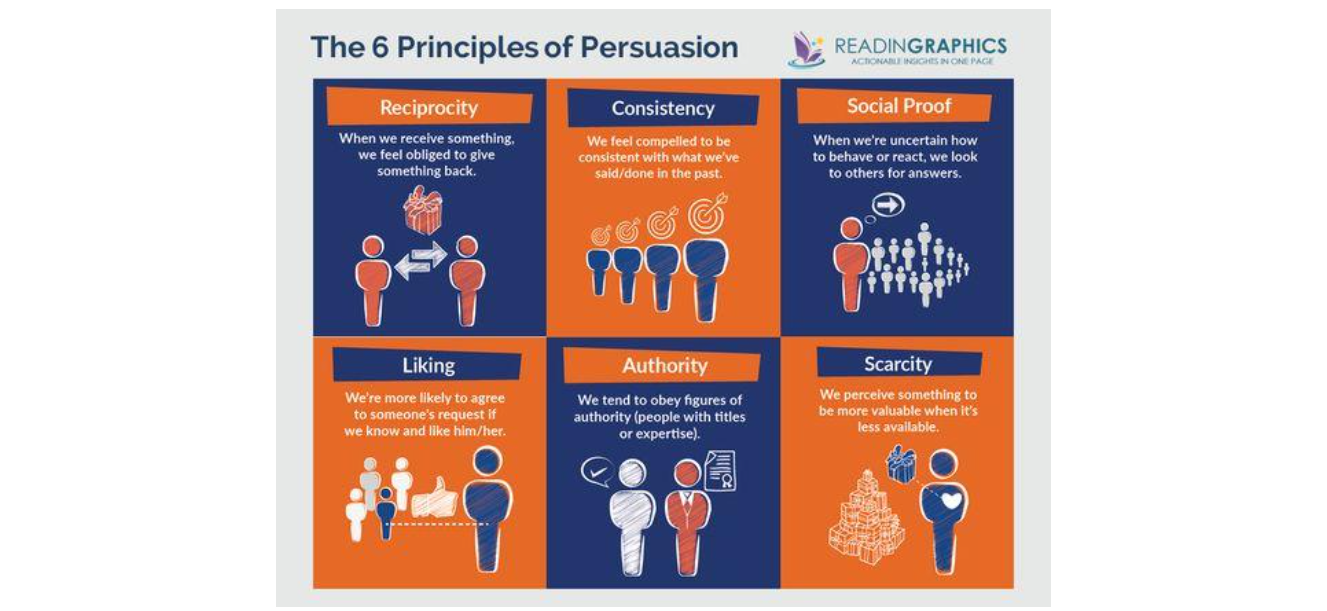

During the 2012 Presidential election, Barack Obama assembled a ‘Dream Team‘ of behavioral scientists, including Robert Cialdini, an Emeritus Professor of Marketing at Arizona State University, renowned for his Principles of Persuasion. One of these principles, social proof, refers to our tendency to follow the choices of those similar to us. In electoral terms, this means that seeing others around us vote for a particular candidate or party increases our likelihood of doing the same. (If the mention of Obama’s campaigns sparked your interest, that’s an example of another principle at play—Authority.)

Any keen observer of Indian elections, particularly in the Hindi belt of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, knows that politically unaffiliated voters often prioritize avoiding a ‘wasted vote’ over voting based on principles. While some may initially justify their choice, deeper probing reveals their reluctance to waste their vote, even if it means not supporting the best candidate. ‘Vote Kharab Nahin Karna Tha (Didn’t want to waste the vote),’ they often admit. But how do they determine the likely winner before casting their vote? Through discussions with those around them. This phenomenon explains why, even during wave elections, a few Independent candidates unaffiliated with any party manage to secure victories. It’s a clear example of Cialdini’s principle of Social Proof in action.

For Social Proof to be effective in electoral politics, political workers must be engaged and motivated to consistently promote their party and, closer to election day, their candidate. This requires workers to feel a genuine connection with the party—a connection fostered by being heard and seen. Unfortunately, this sense of belonging appears to be lacking within the Congress party.

The Peter Principle and Rahul Gandhi’s Mismanagement

Peter’s principle of organizational behavior says that people rise to their level of incompetence in their organization. You reach a level in an organization beyond which you don’t have the required competency or skills.

In Indian politics, there exists a three-tier hierarchy. At the first level, politicians are adept at handling tasks at the Block or Tehsil level, such as those involving the Block Development Officer (BDO). These individuals are typically part of a party’s district organization and contest elections at the village level or as ward councilors in urban areas. The second level comprises politicians capable of managing affairs at the district or Sub-divisional level, including interactions with the District Magistrate’s Office. These leaders are suited for assembly elections, where they can serve as MLAs or represent the state organization. Politicians at these two levels often lack the exposure or confidence to engage with people from diverse cultural backgrounds, as their focus remains on their local constituencies. The third level includes politicians who can collaborate effectively with senior IAS officers and the bureaucracy at the state or central level. These leaders are equipped to participate in national organizations, contest parliamentary elections, and contribute to policymaking at the national scale.

In a well-functioning political organization, an informal hierarchy links national-level politicians to state-level leaders, who, in turn, connect with district-level representatives. This structure ensures that leaders at each level possess the skills necessary for their roles. However, the system depends on two key factors: political workers must aspire to advance through the ranks, and the organization must provide a framework that supports such progression. Under Rahul Gandhi’s leadership, the Congress party has failed to establish these foundational conditions.

Dynastic politics, where the children of influential leaders are elevated to prominent party positions without progressing through organizational ranks, undermine morale among workers and disrupt the opportunity ladder within the party. Similar issues arise when outsiders are brought into the party and immediately given influential roles, or when individuals are rewarded for their closeness to a leader rather than their contributions to the organization. Despite occasional successes, such as the Bharat Jodo Yatra, which briefly energized the party base, Rahul Gandhi continues to repeat these missteps.

In February, the Congress party undertook a significant organizational reshuffle, appointing new General Secretaries, state in-charges, and a new state chief in Maharashtra. In Bihar, which faces elections later this year, the party introduced a new President and reorganized the state structure. These changes bear the influence of Rahul Gandhi, Leader of the Opposition in Lok Sabha, rather than the party President, Mallikarjun Kharge. Figures like K Raju and Krishna Allavaru were assigned roles in Jharkhand and Bihar, respectively, seemingly due to their proximity to Rahul Gandhi, despite their limited experience in electoral politics.

Perils of The Showman Politics

To counter the BJP’s targeted smear campaign against Rahul Gandhi, the Congress party initiated the Bharat Jodo Yatra, followed by the Nyay Yatra. Unlike traditional public outreach campaigns, where politicians traverse cities, meet workers, stay in their homes, and engage in spontaneous gatherings in public spaces, these new efforts resemble curated events. They feature special caravans for accommodation, hotel-ordered meals, and staged communication programs akin to film promotions. There is little genuine effort to connect with party workers, aside from a few polished interactions designed for social media. Lower-level Congress leaders have adopted similar practices, often spending their visits to various cities loitering in 5-star hotels under the guise of press briefings or election management. Guided by local office bearers, they frequent tourist spots but rarely step out to engage with grassroots workers.

It’s not that the Congress party lacks the knowledge or capable individuals to bring about change. Rishi, an IT consultant who volunteered for the party in Varanasi during the 2022 assembly elections, shared an example: ‘The Congress has leaders like Satyanarayan Sharma, a Chhattisgarh stalwart and seven-term MLA, who rented a modest three-bedroom flat in Varanasi to oversee election preparations. His flat became a hub for workers, drawing more visitors in the mornings and evenings than the party office or any candidate’s residence. He visited so many workers’ homes that, within weeks, ordinary members began urging him to contest the election himself.’ When leaders like Sharma are not at the front, it sends a message to workers that the party values glamour over dedication. Disillusioned by this, Rishi has since stopped volunteering for the party.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), backed by substantial resources and the grassroots support of the RSS, contests elections with relentless determination on all fronts. Opposition parties relying solely on the personality cult of their supreme leader will struggle to achieve sustained success. As Samajwadi leader Sudhir Panwar observes, ‘In the past, elections could be won with a 26-28% vote share, often secured through a combination of a charismatic leader and committed caste-based support. However, the BJP has raised the bar, requiring over 40% of the vote share to secure victory.’ For the Congress, as the largest opposition party, this underscores the need for a robust political organization. Without such a foundation, it faces significant electoral disadvantages, particularly in state elections that are crucial for strengthening its presence in the Rajya Sabha. To counter these challenges and defend the constitution effectively, the Congress must urgently address its organizational shortcomings and align itself with the fundamental principles of Indian politics.