JanGopal and Bhakti tradition: Relevance in 21st Century India

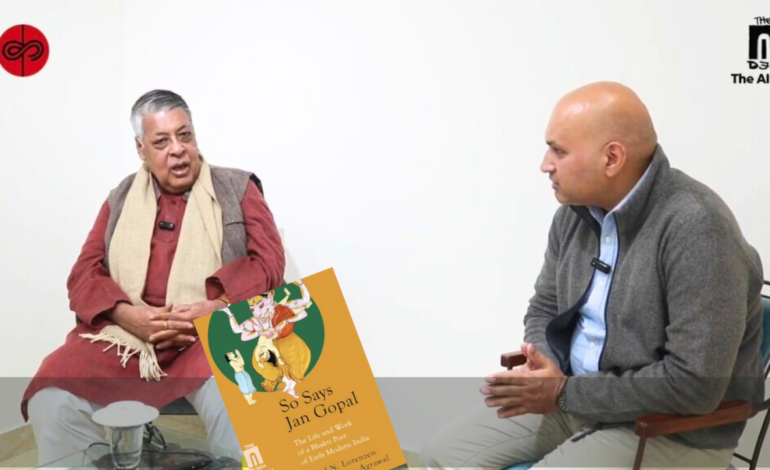

This is the English translation of the transcript of a ‘Book Baithak‘ discussion in Hindi. The Book Baithak is a new series produced jointly by The AIDEM and Ka The Art Cafe, Varanasi. The series focuses on discussing books and authors relevant to contemporary India.

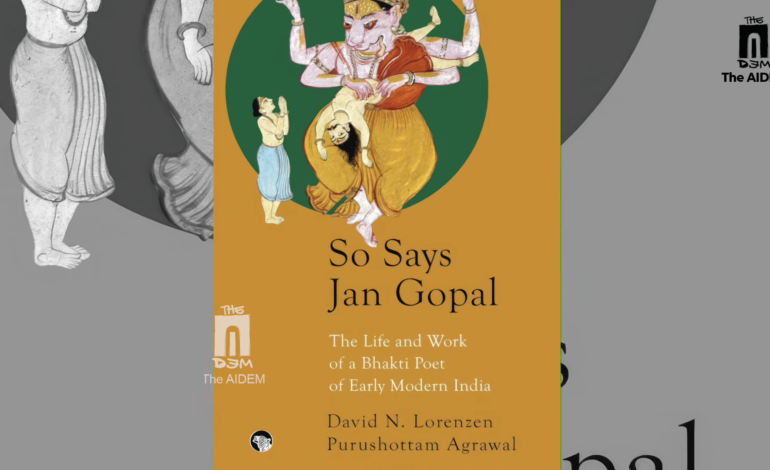

In the first episode of the series Gaurav Tiwari, Entrepreneur and writer based in Varanasi, talks to renowned author Purushottam Agrawal about his new book,”So Says Jan Gopal: The Life and Work of a Bhakti Poet of Early Modern India.” The book is jointly written with David N Lorenzen.

JanGopal was a 16th-century poet from the Bhakti tradition, known for his allegiance to the nirguni (formless divine) movement led by his guru, Dadu Dayal. His work, particularly the ‘Dadu Janam Lila’, celebrates the life of Dadu Dayal and reflects a strong anti-orthodox stance on social norms.

In the interview, Agrawal discusses how JanGopal’s ideas and the Bhakti tradition can be relevant in contemporary India, emphasizing themes of liberation, social equality, and resistance to orthodoxy.

Gaurav Tiwari: Sir, let’s talk about your new book “So Says Jan Gopal”. What motivated you to write this book?

Purushottam Agrawal: Actually, you see, JanGopal is a very important figure from the early modern or medieval period.

Gaurav Tiwari: Which period is this, sir?

Purushottam Agrawal: I’ll explain. JanGopal was active in the seventeenth century and was a disciple of the famous saint Dadu Dayal. It is believed that Dadu Ji passed away in 1603. JanGopal wrote “Dadu Janam Lila,” the biography of Dadu Ji, in 1620. Students of Hindi literature know that the biographies of saints from that period were rarely written by their direct disciples. Anant Das wrote several biographies, but he was neither a contemporary of Kabir nor did he write during Kabir’s lifetime. “Bhakt Mal” was also written after the lifetimes of the subjects. However, “Dadu Janam Lila” is the only biography written by someone who lived with the protagonist for at least 18 years.

Secondly, it uses the familiar idiom of miracles but also includes early examples of rational skepticism. Thirdly, and most importantly, it provides descriptions of events with dates and accurately names historical figures, both significant and ordinary. It is a biography written in the seventeenth century that possesses many characteristics of modern biographies.

The book also describes dialogues between Dadu and Akbar. Many believe that Dadu and Akbar never met, but David and I believe that they did, and we have provided reasons for this in the book. When Akbar sent an invitation to Dadu, he referred to him as the Kabir of his time.

Nowadays, there is a trend to consider Kabir, Tukaram, and others as marginal figures. In my book “Akath Kahani Prem Ki,” I have argued that these figures were never marginal in Indian society. When Jan Gopal describes Dadu’s dialogues with Akbar, Dadu does not quote any authority—neither the Vedas, the Puranas, nor the Quran. He only quotes Kabir, and these quotations are authentically found in Kabir’s works.

The book also mentions dialogues between Dadu and Man Singh. People had complained to Man Singh that Dadu had corrupted both Hindus and Muslims. Dadu’s daughters were of marriageable age but had not been married. Dadu criticized child marriage without quoting any authority, instead appealing to experience. Dadu argued that young girls married off early and who then become widows often go astray, causing distress to their families.

According to Jan Gopal, Dadu argued that societal malpractices should be criticized based on experience and essential human reality, rather than quoting any authority.

Gaurav Tiwari: Sir, why is it significant that Jan Gopal doesn’t quote any authority? Because nowadays, when we read articles in newspapers, we often find that they quote other professors. In Sanskrit, even if a verse is written recently, it is often considered ancient and authoritative.

Purushottam Agrawal: Absolutely correct. The most famous example is, “आ सिन्धु-सिन्धु पर्यन्ता, यस्य भारत भूमिका: पितृभू: पुण्यभूश्चैव स वै हिंदुरिति स्मृत:”. Savarkar included this at the beginning of his book “Hindutva,” and many people believe that it is a verse from the Puranas, but it is actually composed by Savarkar himself and is not found in the Puranas. This is why it is significant. Very good question.

Let’s understand the context of that time when we are talking about the seventeenth century. At that time, authority and scripture were very influential, and challenging them was very significant. This was happening worldwide, even in Europe, where the authority of the Church was being challenged. And the entire tradition of the Church Fathers was being challenged. You couldn’t argue within that paradigm.

For example, if someone says the earth is round, but the Church Fathers say that Ptolemy has proven the earth is flat, whom will you quote? When there is a paradigm shift in epistemology, the authority of the prevailing paradigm becomes insufficient.

In a social context, if we talk about a 16-year-old girl’s marriage, or if a 17-18-year-old girl gets married, she has to endure loneliness and distress for the rest of her life. There is no need to quote any authority for this. What Jan Gopal and I are saying is that if such a situation arises before me, why do I need to quote any authority to prove that no one is born superior or inferior?

Based on your belief, no one is a non-believer or a believer. Whether you accept my creed or not, if you do not believe in Prophet Muhammad as the last prophet of Allah, does that mean I don’t have the right to live? Now, if I am born into a particular caste, do you want to consider me untouchable just because of my birth?

Therefore, instead of quoting any authority, why not appeal to the innate sense of justice? The importance of reason and justice should not be diminished.

John Rawls, a philosopher of the 20th century, proposed the theory of the veil of ignorance. The most interesting part is that you imagine a society as you would want it to be, and you do not know whether you are a man or a woman, black or white, Indian or Chinese. Now, imagine that you have envisioned a society where women should be kept in their place. When the veil is lifted and you realize that you are a woman, how would you feel?

It is very interesting. He rightly pointed out that there is an inherent sense of justice within all humans. Gandhi called it the voice of conscience. I don’t use the metaphor of the voice of conscience, but it exists. Jan Gopal’s Dadu appeals to this.

Gaurav Tiwari: Sir, so the question arises, what is Bhakti, and these Bhakti poets, if we compare this to today’s AI era, why is it relevant today? For those working outside the Hindi academics, for a common reader, why should they know about Bhakti? Why is Kabir important for them, or is Kabir even important?

Purushottam Agrawal: Absolutely correct, very good question. I often ask myself and present this question to my literature and history students. When we talk about Bhakti, we need to understand two things. If you look at the history of Bhakti or its historicity, the original meaning of Bhakti is participation. If you look at ancient examples, how these words were used in classical Sanskrit, if you look at texts like Vyas and Panini, the meaning of Bhakti is participation, and a Bhakta (devotee) is a participant.

According to Vyas, Indra and Agni are both Bhaktas of each other, which means that if you offer something in a yajna (sacrifice), even if you offer it in the name of Indra, a part of it will also go to Agni. They are participant shareholders.

Laxman Swaroop, in his translation, used the term “Simple and Company.” Speaking of Panini, his work is a descriptive grammar that describes the uses of language. A very important book is “Panini Kalin Bharatvarsh” by Vasudev Sharan Agrawal, who was a legendary professor at your university (Banaras Hindu University).

In Panini’s work, the words Bhakti and Bhakta are used to mean love and attachment. Now you see, Bhakti has a technical meaning as a devotee of God, but we also say “deshbhakt” (patriot) and “rajbhakt” (loyal subject). We can also say, “No matter what you eat or drink, I am a devotee of coffee; the rest of the world’s things on one side, I am a devotee of poori.” So, the word Bhakti indicates love and attachment.

Therefore, in today’s political dialogue, where the word Bhakti is used, ignoring that, Bhakti generally means blind love. Historically, this general meaning gradually turned into a kind of submission. In the 12th-13th centuries, saints like Namdev, Kabir, and Tukaram rediscovered the old meaning of Bhakti as participation. Here, submission means the submission of a defeated soldier in war, and the surrender of love. A defeated soldier surrenders, and you also surrender for your love—for the love of a woman, a son, a wife.

The beginning of this situation is considered to be from Namdev, as Anant Das in his “Namdev Parichay” states that Namdev was the first devotee of Kalyug who brought Hari under his control.

In Namdev’s work, Bhakti re-emerges as a participant. The relationship with God is one of equality, so how can birth-based discrimination be considered justified in society? Kabir’s line is: “Tum kat Brahman hum kat Shudra, hum kat lohu tum kat doodh.” This is a fundamental question, and there is no scriptural answer to it. If we are superior or inferior by birth, there should be a solid basis for it.

For example, in English, the phrase “blue blood” indicates royalty. But the truth is that everyone’s blood is red. So, in this era, Bhakti rediscovers its old meaning with new connotations.

Now, what is the importance of this in your own life? First of all, it is very important to read these poets, especially Kabir and Tukaram. They are not only devotees but also high-caliber poets. In fact, any great poet is a philosopher, and any great philosopher is a poet.

The work of these poets is to address the fundamental questions and existential topics of life. For example, the slogan of the Yug Nirman Yojana was: “Hum badle jag badla, hum badle yug badla.” This is a half-truth because just by changing yourself, the era won’t change. If the social system gives a premium to dishonesty, dishonesty will prevail.

The idea that the system will change and human beings will automatically improve is also incorrect because humans are not just inanimate entities; they are living beings. They are part of existence and interact with it. They do not simply respond to the system.

If you lift this plate and throw it down, it will break. But if it were a human or an animal, it would try its best not to fall. Even an insect, if you try to crush it, will struggle and try to escape.

Consciousness means intervention in the given situation. That is what consciousness means. Therefore, both aspects are true, and this insight can be found in your experience. For example, in Kabir’s famous lines: “Mai kai vidhi kath gambhira, bheetar kaho to jag mein laje, baahar kaho to jhootha loo. Mai kai vidhi kath gambhira, bheetar baahar sabad nirantar, mai hi vidhi kath gambhir.” If I say that the ultimate truth is within me, then what about the whole world? I am insulting it, shaming it. If I say it is outside, it is false because you feel it within yourself. My Ram resides in my heart.

What is reality? Reality is the constant interaction between the inner and the outer. This is a very abstract philosophical concept. If you live in an environment where there are abuses from morning to evening, take the example of social media. The kind of language young people use on social media today is not even used privately among close friends in my generation. Is it true or not, let’s ignore the language. The kind of violence you see, the language of protest, and the normalization of violence—think about it yourself. If, after this conversation, you read or hear that people have eaten a child after cutting it into eight pieces, you won’t feel nauseated. I won’t feel nauseated because we have become accustomed to it. Cruelty has become normalized. I am not cruel, right? You are not cruel, so you are still sensitive within. But the environment has made you so insensitive that cruelty doesn’t affect you as it should.

Therefore, the poet who reminds you of the interaction between the inner and the outer, I have said this using Kabir as an example. You can use anyone’s example. I really like a famous line of Meera Bai: “Chahe koi baind do, chahe koi naind do, main to chaal chalungi ati rana ji mane.”

The fear of defamation stops you from doing many things, doesn’t it? What will people say? Even if you are doing good work, you feel afraid. If you are doing bad work, you feel afraid. So, whether your work is right or wrong should not depend on what people will say. If there is a riot in the neighborhood and someone is being beaten, and you don’t intervene because you think, “If I save him today, my people will call me a traitor tomorrow,” you are making a mistake. If you avoid doing bad work because of what people will say, you are doing the right thing. But ultimately, the decision will be made by your conscience.

So whether someone praises or criticizes, I will continue walking my unique path because I am not afraid of defamation. I like defamation. These kinds of connections and associations, and imagining such situations, give you strength and show you the way.

Therefore, I believe that literature, especially Bhakti literature, is important for understanding Indian society. If you go to England, for example, Shakespeare is still called the national poet of England. But no taxi driver or porter in England quotes Shakespeare. They know his name, are proud of him, but they don’t quote him. In Banaras, in any city in India, a rickshaw driver quotes Tulsidas and Kabirdas. In Maharashtra, a rickshaw driver quotes Dnyaneshwar and Tukaram. This means that these poets are not just classical poets; they are contemporary to our time as well. Not just for you and me, but for ordinary people too. So you and I may not quote Kabirdas, but common people do.

Often, you don’t even realize whom you are quoting. The sayings of poets become part of your idioms, and vice versa. Knowing, reading, and understanding such poets is important to understand your time, your world, and your surroundings. Reading and understanding Bhakti poetry is essential for these reasons.

Gaurav Tiwari: One thing is that there are many issues of human existence, meaning the problems of being human or the problems of living in a society, which have been problems in every era. Their forms may change, they may be different. For example, the problem of war—2,000 years ago, people fought wars in a different way, and today they fight wars differently. Violence against each other, imperialism, hatred for each other, the desire to earn a livelihood—these are all parts of human existence. So, how does the wisdom we need to improve ourselves and society, how does Jan Gopal help in that?

Purushottam Agrawal: As I mentioned in the example, Jan Gopal reminds you that even in the 17th century, there was a person, Jan Gopal himself or his guru Dadu, who did not wait for any scriptural authority to call a wrong thing wrong. This exercise of wisdom not only highlights the importance of wisdom but also their courage and serves as an inspiration for us. In this way, JanGopal is talking about great wisdom.

One thing we should keep in mind is that what we call wisdom should not be limited to your own tradition and civilization. Wisdom means the accumulated knowledge from all human experiences so far, from which conclusions are drawn. For example, the gas chambers built in Hitler’s Germany where Jews were burned. We cannot understand that there is no lesson in this for us. Whether for the Chinese, the Americans, or just the Germans, there is a lesson. Democracy, as we know it today, was invented in the modern era. Ancient times were different, but its invention was in Europe in the modern era. This does not mean that democracy is a good thing only in Europe and useless elsewhere. The universality of wisdom is very important, and for that, it is not necessary to adopt something lock, stock, and barrel.

Watch the full interview below: