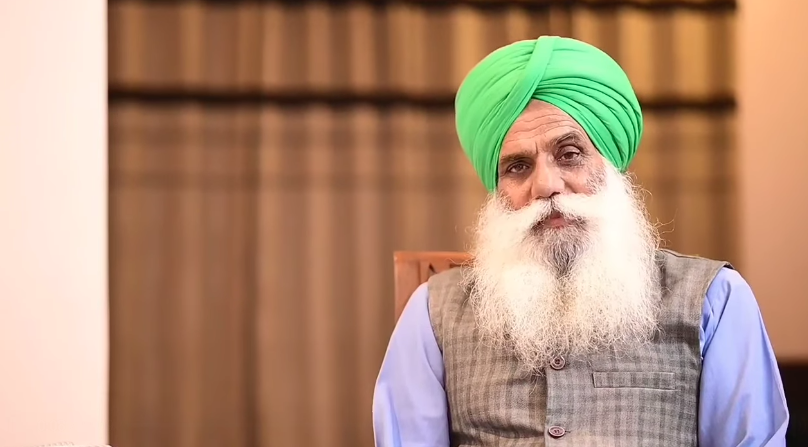

On 5 March 2025, one hundred days had passed since Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s protest fast. Discussions continue on issues like the minimum support price (MSP) for crops, other demands put forth under the aegis of the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (non-political) and Kisan Mazdoor Morcha, negotiations with the government, and coordination with the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM). Additionally, Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s protest fast also continues. However, if it extends further, there is a serious fear of it turning into a ‘maran vrat’ (fast unto death).

As a result of the farmers’ protest at Delhi’s Singhu border in 2020-21, the government withdrew the three agricultural laws. Since then, a yaksh prashn (fundamental question) has emerged—how can the country’s vast agricultural sector survive amidst the rapidly increasing corporatization of education, healthcare, and public sector enterprises?

Economists have yet to raise concerns about the private capital being revered in corporate India—how much of it is actually looted public money?

It is hoped that economists like Professor Arun Kumar, who has extensively studied the role of black money in the Indian economy, will also examine this central issue. Whatever the case, a decisive turning point in the clash between farmers and corporate powers is not expected anytime soon.

However, one certainty remains: Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s fast, having crossed 100 days, has become a landmark in the history of nonviolent resistance to injustice.

The significance of this fast grows even further when we recognize that it has restored the credibility, dignity, and strength of protest fasts. I do not wish to discuss fasts staged for self-promotion, but I would like to highlight the observation made by Abhimanyu Kohar, convener of the year-long protest at the Khanauri border. He pointed out that while the media covered Anna Hazare’s 13-day fast in 2011 round the clock, it has largely ignored Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s prolonged fast, giving it only a fraction of the same coverage.

In fact, this comparison itself is flawed. The truth was evident from the beginning—Anna Hazare’s fast was designed for media attention. The powers and intentions behind that episode were never a hidden secret. The outcome reflected this as well—India’s national and social life became increasingly ensnared in the corporate-communal nexus.

Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s satyagraha-fast has consistently maintained seriousness, dignity, and humility. He and the farmer leaders supporting the movement have refrained from turning the fasting site into a platform for speeches. This has reinforced the belief that the long-cherished value of “weighing words before speaking” has not been entirely lost in the din of modern verbosity.

Needless to say, Jagjit Singh Dallewal had mentally and physically prepared himself for this fast. Before undertaking it, he completed certain worldly duties to detach himself. Even some of his closest associates did not initially realize that he was truly embarking on a ‘maran vrat’.

Through his fast, Jagjit Singh Dallewal has ushered in a small yet significant revolution in the non-violent mode of resistance—a single individual standing up fearlessly against injustice through satyagraha, civil disobedience, and fasting. Mohandas Gandhi employed this method of resistance in India’s freedom movement, drawing inspiration from global sources. Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, describing Gandhi’s nonviolent action as the most revolutionary aspect of his teachings, wrote:

“The greatest revolution of our time is, therefore, a procedural revolution—the removal of injustice through a mode of action characterized by justice. The question here is not so much the contents of justice as the mode to achieve it. Constitutional and orderly processes are often inadequate. When they fail, weapons are used. To prevent this and to ensure that man is never caught between the ballot and the bullet, this procedural revolution of civil disobedience has emerged. At the head of all revolutions of our time stands this revolution of satyagraha against weapons…”

(Marx, Gandhi, and Socialism, pp. xxxi-ii)

It is widely acknowledged that the three agricultural laws withdrawn by the government will eventually be reintroduced in some form. The government itself had stated, “The laws are being withdrawn, not completely repealed.”

This is inevitable due to the neoliberal consensus among the country’s political and intellectual elite. However, this does not diminish the need for resistance or its value. As long as even a single citizen opposes corporatization and upholds the principles of freedom, self-reliance, and sovereignty, the need and significance of resistance will persist.

Governments can fire bullets. They can manipulate elections. However, citizens who dissent have the option to resist—at the risk of their own lives. Jagjit Singh Dallewal’s satyagraha-fast is an open, non-violent rebellion against the government’s corporate-driven policies. Lohia, at the conclusion of his earlier statement, noted that despite its moral strength and righteousness, non-violent resistance has “only made a faltering appearance to date.”

The ongoing protest fast at the Khanauri border is a reassurance that this form of resistance is far from obsolete. It has revived the non-violent mode of protest against injustice, restoring faith in its credibility, dignity, and strength.

This article was first published in Punjab Today News and can be read here.

Covering this genuine movement is apt tribute to that. From ancient Kings’ period to present Democratic days, farmers are the ones the most sufferers.