Before Empuraan reached theatres, it faced a different kind of battle—not on screen, but off it. In a country where the line between offense and art keeps shifting, filmmakers now direct with one eye on the story, and the other on the censor’s scissors. Is that still cinema? Or a performance tailored for fragile sentiments?

Can a few cuts curtail the Chaos?

Towards the final few sequences of Empuraan, we see the fate that befalls Munna– a religious fundamentalist who acted as accomplice to the massacre of Muslims during the 2002 riots. He is blown to smithereens.

Munna’s master, Baba Bajarangi, awaits a more tortuous end.

Disarmed and watching his men fall like flies, Bajrangi helplessly witnesses Munna’s explosion; shreds of his beloved’s skin raining down around him. Moments later, Baba Bajarangi is gunned down by an undeterred stream of bullets fired by Zayed Masood.

This is the backstory that propels the movie Empuraan throughout. Regardless of the way the plot develops and derails, Zayed Masood’s vengeance is at the core of Empuraan. This is the choice made by Director Prithviraj, who also happens to play the role of the older Masood.

In his interview with the film- critic Anupama Chopra, Director Prithviraj Sukumaran refers to the technical finesse, fight choreography, and high- budget production as “superficial layers”. The film derives its affective power from the sheer despair undergone by a young Zayed Masood as he witnessed the slaughter of his entire family in silence.

In 2016, Prithviraj Sukumaran, Mollywood actor, announced his directorial debut via Facebook. Three years later, ‘Lucifer’ (2019), featuring one of Malayalam’s most celebrated actors, Mohanlal, hit the screens. In less than two weeks of its theatrical release, ‘Lucifer’ hit the hundred- crore mark, a historic milestone catapulting the movie into the list of the highest- grossing Malayalam films.

Based on interviews given by Prithviraj, two more movies are part of ‘Lucifer’ franchise; ‘L2: Empuraan’ (2025), the sequel of ‘Lucifer’, being the latest in the installment. The director cum actor was always determined to take Malayalam cinema to a wider audience, often citing that Malayalam film industry had great untapped potential to go “Pan India”.

India, a country where the Hindi- speaking Bollywood enjoys the most visibility and privilege, is also home to several regional film industries. Telugu films, Bahubali (dir: S.S Rajamouli) and Pushpa (dir: Sukumar), Kannada film K.G.F (dir: Prashant Neel) are, but, few movies that, by being dubbed into multiple Indian languages, were successful in reaching diverse audiences across India. Distributing ‘Empuraan’ world- wide was intrinsic to this aspiration to go “Pan India” in full throttle, or perhaps, even transcend that category.

For the director, a series of serendipitous interventions was crucial to the success of the movie.

‘We had no plans of an IMAX release’, he responds during a panel interview.

‘The film was shot in anamorphic format, which is not the most ideal rendering for an IMAX screening’, he goes on. ‘When the teaser of the film was put out, IMAX’s head, Mr. Christopher Tillman contacted us the very next day and pitched for an IMAX release.’ Given the scale, Prithviraj acknowledges he was overly ambitious.

After months of intense hype, ‘Empuraan’ was released world- wide on March 27th. Amidst all the fanfare, controversies erupted. The film’s popularity invited ire from Right- Wing supporters, who were upset at the portrayal of Hindu leaders’ accused of spear- heading the 2002 Gujarat riots. The RSS backed magazine Organiser decried the film as “anti- Hindu” propaganda and, therefore, “anti- Bharat”.

Interestingly, what leads to the denouncement of the film by Hindu Right- Wing is the distortion of history behind Godhra riots. Matters have escalated to such an extent that BJP Kerala’s leader, B. Gopalakrishnan branded Prithviraj’s spouse, Supriya Menon, as an “urban- naxal”– a flummoxing term coined in the wake of the 2016 JNU protests. Prithviraj’s family is at the receiving end of virulent cyber attacks. For a director who admittedly wanted to push the boundaries of what is considered as “pan- India”, the boundless surge of collective violence imposed the limit.

Empuraan is an action- heavy political thriller centering Stephen Nedumpally (played by Mohanlal), who goes by the pseudonym, Lucifer. In the first installment of the Lucifer universe, we see Stephen Nedumpally flee Kerala following a smear campaign carried against him by his political rivals. Later, it is revealed that Nedumpally’s underground persona is known as Khureshi Ab’ram. Traversing continents in private jets, Khureshi Ab’ ram is on a mission to bust drug cartels. As the political landscape grows bleak in his homeland, Stephen AKA Khureshi feels obligated to return and rescue the state of Kerala from falling into the hands of religious extremists. With the incumbent ruling party in the state entering into an alliance with the party in power at the center, things have taken a turn for the worse. The only way out is to exterminate the leaders of the national party, a task Khureshi commits himself to, with the aid of his protege, Zayed Masood, who witnessed the macabre death of his family members in 2002.

To avenge the murder of his kin and manifest a certain poetic justice, Masood kills Baba Bajrangi.

All of this has spurred the outrage against the movie.

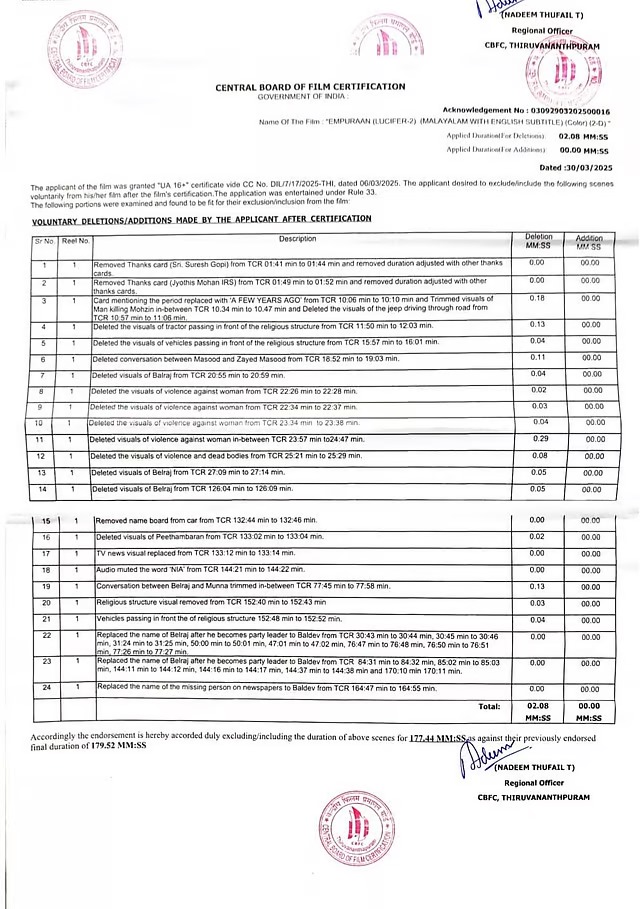

Following the backlash of Hindu- majoritarian groups, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) issued a notice for enacting seventeen cuts to the original version of Empuraan. In total, twenty four cuts have been made by the film- makers. The makers have removed explicit references to the Gujarat riots, mention of NIA, in addition to changing the name of Baba Bajarangi, the character prime accused. The CBFC also recommended the removal of certain scenes for their depiction of violence against women. The movie also shows the rape of a Muslim woman by Baba Bajarangi’s cohort of men in a gratuitously violent manner.

As triggering as the scene might be, real history offers even darker horrors: a carriage set to fire, a fully pregnant woman’s belly torn apart, and her fetus, extricated with the nib of the sword.

In 2023, Babu Bajrangi (alluded to by the name of the character Baba Bajrangi, in Empuraan), henchman of the Bajrang Dal, the youth wing of Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), and the key conspirator behind the Naroda Patiya massacre was acquitted by the court, alongside sixty- six others. Bajrangi was accused on charges of the murder unleashed in the Muslim dominated locality of Naroda Patiya. In his own words, Bajrangi has proudly expressed the horrors he inflicted in an undercover interview recorded by the Tehelka magazine.

The backstory of Zayed Masood (played by Prithviraj) uses the narrative Godhra riots as a launchpad for establishing the motive of the character, thereby implicating the perpetrators. Former BJP Kerala member, V.V. Vijesh, filed a petition to the Kerala High Court, arguing Empuraan fuels communal violence. Succumbing to the mounting political pressure, the film- makers have made twenty four cuts in Empuraan. Meanwhile BJP Union Minister from Kerala, Mr. Suresh Gopi, has dismissed all of this as an orchestrated PR stunt. Ironically, the film starts with a title card thanking the minister (which is now removed).

All that is Censored, All that remains Intact

Media scholar and researcher, Someswar Bhowmik surveys the history of censorship in India– starting from the colonial period, moving on to post- independence and finally, the post- liberalization period. In his book ‘Cinema and Censorship: Politics of Control in India’, published in 2009, he examines a couple of contradictions inherent to the act of censorship. One such issue with censorship guidelines is quoted below:

‘First, an underlying assumption runs through the guidelines that deleting or modifying footage can sanitise an objectionable film or any portion of it. It is thus assumed that any part of a film is revisable and it would still be the same, and would make sense. Such a mindset obviously considers a film to be a discreet amalgamation of disconnected footage.’ (p. 338)

As Bhowmik (2009) argues, there is only so much that you can truncate in a composite medium like a film. Empuraan’s plot, despite all its flaws, hinges on Zayed Masood’s backstory– rendered with cuts or otherwise. In other words, cuts won’t simply cut it.

In their co- written piece on the aftermath of Gujarat riots, sociologist Shiv Visvanathan and human rights’ activist Teesta Setelvad, argue the efficacy of narratives in ascertaining the citizenship status of minorities. They discuss how the disruption of daily life by riots produce a form of vulnerability that is not exceptional. Survivors of riots are constantly exposed to vulnerability. Rather than a product of temporary rupture, vulnerability is continuous here, lending itself to the everyday lives of survivors. Visvanathan and Setelvad write, ‘narratives create the chain of being that we call the “citizen” ’. When narratives are upended by the onslaught of violence, people become vulnerable. In its turn, vulnerability performs the task of collecting the scattered fragments of the narrative- structure, and allows a person to live on. The authors remark, ‘the riot is always a fragment of a society gone wrong’.

Perhaps, this is a reason why civil society organizations, human rights’ activists, academics and journalists recorded statements of the survivors and witnesses of the riots.

The young Masood lives on to tell his tale of the ghastly night and the mob that butchered his family. Being a fictional character, he is able to reclaim the wholeness of his ruptured narrative. Unlike the people who survived the riots by clasping to the fragments, Masood is presented an opportunity: to distend the fragment and rehabilitate it within the fullness of narrative.

Perhaps, Prithviraj was not conscious of the repercussions of his decision to frame Masood’s character around the contentious background of Gujarat Riots .

To make a ‘Pan- Indian’ movie, Godhra riot was picked as the lynchpin. Despite the ideological inconsistencies of both Prithviraj and Murali Gopi (the script- writer), the riot was invoked to enrich the appeal of ‘Pan- Indian’–ness. Gujarat riots, as an event, symbolize an irreparable wound afflicted upon the body- politic of the Nation- State. Somehow, the stifled history of carnage motored the aspiration of the film to be ‘Pan- Indian’. A big- budget commercial flick, Empuraan strived to embed itself in public consciousness as an expansive project coming from the modest Malayalam film industry. With its mass appeal, it also mobilised a majoritarian sentiment of ‘hurt’.

The prominent feminist scholar and cultural theorist, Sarah Ahmed, writing against the context of anxieties surrounding the influx of immigrants to the United Kingdom, makes an interesting observation: the ‘other’ becomes the source of the majority’s feelings. The White subject feels injured at the thought of the ‘other’ laying claim over or looting his or her national resources. The nation- state, like the human skin, is soft and easily bruised. This metaphor of “soft- touch” is deployed to further tighten the regulation of immigration to the country.

Empuraan only briefly touches upon the Gujarat riots, before it proceeds to depict large- scale visions, multiple, dramatic entries and other tangential issues (the problem of drug mafia worldwide, partisan politics in Kerala, deflection of political figures, among others). Regardless, the Sangh and its proponents were deeply upset at what they claim to be a distortion of truth and “white- washing” of Islamic terrorism. As a teenager, Zayid Masood is rescued by Abaram Khureshi (Mohanlal), from the clutches of Islamic fundamentalist group, Lashkar- e- Taiba. Growing up as Khureshi’s disciple, Masood learns to detach the animosity he harbors towards the Hindu terrorists from his religious identity as a Muslim. This topic warrants a completely different discussion on representations and identities, and is beyond the scope of this article. Despite the portrayal of Masood as a man animated by personal vendetta, as opposed to a collective hatred towards his rivals (solidified by his belongingness to a religious fold), Right- Wing forces who critique the movie antagonise him for his religious identity. To rephrase, Masood, according to the film- makers, is primarily driven by revenge for the personal loss he has suffered. When he kills Baba Bajarangi, he does it in primarily in retaliation towards Bajarangi’s murder of his kin, over Bajrangi’s genocide of an entire community.

The real villain of #Empuraan?

Baba Bajrangi (Abhimanyu Singh) appears inspired by Babubhai Patel, aka Babu Bajrangi, a Bajrang Dal leader convicted for his role in the 2002 Naroda Patiya māssacre during Gujarat gen0cide, where 97 Muslims were killed.#GujaratRiots #Mohanlal𓃵 pic.twitter.com/Sy7XvVGLO2

— أمينة Amina (@AminaaKausar) March 29, 2025

To read the hostility directed towards Empuraan, I revisit Ahmed’s argument.

By privileging the pain experienced by normative subjects, and pandering to the demands made by supporters of Hindutva, regulatory extensions of the state like the censor board (CFBC), to borrow from Ahmed, translates the pain into entitlement. The theorist remarks, “the more access subjects have to public resources, the more access they may have to the capacity to mobilise narratives of injury within the public domain” (p. 33).

What is to be done about the pain of the other then?

Ahmed offers a suggestion, that is, to be capacious while listening to the pain of others. Testimonials of Godhra violence recorded painstakingly by activists like Teesta Setelvad serve this purpose. These fragmentary narratives resist the tendency to appropriate the pain felt by the dominant party as the nation’s pain.

Quoted below is an excerpt from a testimonial collected by Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP):

‘Terror still haunts 13-year-old Gyanprakash as he bursts into tears from time to time. “I cannot forget the sight of people burning in front of me,” he says while recuperating at the Ahmedabad city hospital.’

Gyanprakash was a passenger in the Sabarmati express on February 27th, 2002. The arson of the S-6 coach of the train was used to justify the genocidal violence unleashed in its aftermath.

On the next day, February 28th, a blood- thirsty mob armed with lethal weapons stormed into Muslim residential areas and left a trail of destruction behind them. Given below is a chilling quote from Bilkees’ testimony as mentioned by Visvanathan and Setelvad in their co- authored piece:

‘They raped my two sisters and me and behaved in an inhuman way with my uncle and aunt’s daughters. They tore our clothes and raped eight of us. Before my very eyes they killed my 3-year-old daughter.”

I have selected the above cases as they merge to form a veracious account closer to Masood’s backstory in Empuraan. The point I wish to demonstrate is that the outcry made by Sangh Parivar’s foot- soldiers over the movie results from a psychic discomfort towards reality. For the normative subject of Hindutva (who is also the ideal citizen), the fantasies regarding the other– particularly, the fear and hatred for the other– becomes necessary in mobilising a collective of like- minded people– people who believe they are different from the demarcated other.