…His Life And Politics Continues to Give The Congress

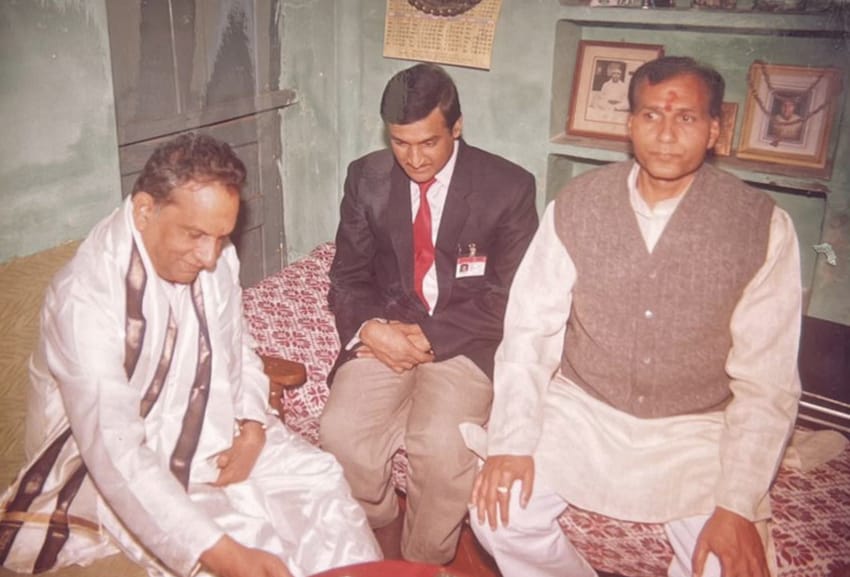

In the last years of his life, Lakshman Tiwari would occasionally laugh off the label that some of his fellow Congressmen gave him— “an endangered species”. More than a dig, it was also an admission of a truth many knew but few wanted to acknowledge: that the kind of Congress culture Tiwari embodied— principled, unbending, unaccommodating to the whims of power, but at the same time with utmost loyalty to the party’s proclaimed ideals —was well on its way to extinction.

Lakshman Tiwari passed away on May 17, 2025 at Varanasi. He was born in 1953, into a wealthy zamindar Brahmin family in the Mohania subdivision of Kaimur district, part of the Sasaram Lok Sabha constituency in Bihar. His political life began even before he turned 18, when Suresh Ram, son of Congress stalwart Babu Jagjivan Ram, contested the Mohania Assembly constituency in 1972. This initiation led to an active student politics life in Bihar, where he completed his B.Sc. He later came to Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in Varanasi, where he pursued a diploma in Russian Studies and a Master’s in Philosophy.

The BHU of the 1970s was a cauldron of vibrant student politics, with the Ram Manohar Lohia – Samajwadi idealism on the one side and the Congress thought professedly inspired by Nehruvian ideals, which were being advanced by Indira Gandhi led organisation in its ways, with both strengths and weaknesses, on the other side. His political activities intensified in a student landscape then dominated by Samajwadi politics.

It was during this period that Tiwari came to know about a conversation between Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, stalwart Hindi litterateur, and then Rector at BHU. Dwivedi was advising student leader RamBhachan Pandey—still active in campus politics in his late twenties—to leave the “school” (university politics) and try his luck in the “university” (the world). Tiwari heard this advice through Rambhachan Pandey, an elder and distant relative. A few years later, Tiwari moved to New Delhi, where he came into contact with the Maratha Congress stalwart of those days, the late Vasant Sathe.

Sathe took an instant liking to Tiwari, treated him like a son, and made him part of his team. Before he turned 30, Tiwari had been appointed to several ministerial committees to ensure financial stability and a political foothold. His dynamic activism, say many of his peers, attracted the attention of a group of young leaders of that time, including those like AK Antony, Veerappa Moily and Priyaranjan Das Munshi. At the topmost level, first Sanjay Gandhi and later Rajiv Gandhi saw much merit in Tiwari’s intellectual attributes and organisational skills.

After Sanjay Gandhi’s demise, when Menaka Gandhi and Akbar Ahmad ‘Dumpy’ formed the Sanjay Vichar Manch, Tiwari joined the outfit briefly. However, when Menaka decided to leave the Congress altogether, Tiwari chose not to rebel. He remained with the Congress. This act of loyalty brought him closer to Rajiv Gandhi, newly appointed as General Secretary in 1982.

During the Rajiv years, he was appointed National Coordinator of a committee comprising young leaders tasked with auditing party activities in every state. He and D.P Ray, then in charge of the Youth Congress, worked closely together. This assignment brought Tiwari into regular contact with Congress leaders across the country, including A.K Antony, Veerappa Moily, P. V Rangayya Naidu, the late Bala Saheb Vikhe Patil, the late Santosh Mohan Dev, H. Hanumanthappa, and the late B. Satyanarayan Reddy.

He spent nearly 25 years as a party observer in various state and national elections. During the last Congress government in Uttar Pradesh (1984–89), he worked closely with Sunil Shastri, son of former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. Among Shastri’s four sons, Tiwari remained closest to the eldest, the late Harikrishan Shastri, and the youngest, Ashok Shastri, who passed away at a young age. When Sunil Shastri left the Congress in 1989 to join hands with V.P. Singh, Tiwari refused to follow. He held firmly to his principle: “Those who are not with the party, I’m not with them.”

The post-Rajiv era in Uttar Pradesh saw a sharp decline in Congress fortunes—a decline that has yet to be arrested. The party’s repeated experiments with inducting leaders from outside its ranks, often with little investment in Congress culture, left many loyalists sidelined. Tiwari, however, remained unaffected. He never left the party, never sought posts or electoral tickets. This was despite his longstanding familiarity with Delhi’s political and bureaucratic corridors, cultivated over 15 years of work with senior Union Ministers. His access could have made him an asset to newer political formations in Uttar Pradesh. Yet he stayed with the Congress. He used to say, “Bapp aur party badli nahin jaati”—one does not change one’s father, or one’s party.

His resolute pursuit of the professed principles of the party was acknowledged from time to time, albeit sparingly. He earned advisory roles in ministries whenever the Congress was in power. These positions, though low-profile, gave him a public life marked by respect, dignity, and influence. He never treated politics as a vehicle for personal enrichment. His refusal to flatter or submit cost him politically but earned enduring respect among Congress stalwarts like A.K. Antony, who when contacted said, “Some bonds cannot be explained over a phone call.” Senior Congress leader Veerappa Moily remembers Lakshman Tiwari as a man after his own heart. “He was moulded in a classical Nehruvian structure. A substantive intellectual with a great political and developmental vision along with supreme organisational skills.” – Moily told The AIDEM.

After 2014, when the BJP reshaped the national political landscape under Narendra Modi—and the Congress adopted a new style under Rahul Gandhi—Tiwari returned to his roots in Assi, Varanasi. There, he focused on local politics: helping people access government schemes, ensuring rightful privileges reached the deserving from the state bureaucracy, and quietly assisting the poor. He came to represent a kind of old-school, observant Hindu—secular in belief and wary of Hindutva. Retired IAS officer Nitin Gokarn, described him as a “philosopher in the real sense,” and credited him for his pivotal role as board trustee in the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor expansion. At home, this secularism took form in small but meaningful ways: his children were taught to address a young Muslim neighbour, who was also his close associate, as Mama (maternal uncle).

Dr. Jitendra Seth, a local environmental activist, recalled Tiwari’s early and steadfast support for the restoration of lakes and opposition to land encroachments. “He didn’t speak at our protests,” said Seth, “but the right calls and directions always came from him.”

Despite repeated attempts, he never secured an official party nomination—passed over in his youth for being too young, and later, for being too blunt. His unwillingness to flatter or submit cost him, again and again. Yet he remained unbothered. Lakshman Tiwari carried political weight—of a kind that is hard to measure in posts or headlines. He believed the party had given him an identity and dignity that were their own reward. Most of the people he once competed with in Varanasi for party positions or tickets have since left the Congress.

Prajanath Sharma, a former District Congress President, aptly captured Tiwari’s essence: “He worked hard, connected with people, and wore his honesty like a second skin. That’s not the style anymore.”

No, it is not. But for those who remember that style, Lakshman Tiwari’s life remains a quiet testament to a kind of Congressmanship the party desperately needs to revive. His commitment to the idea of uplifting the marginalised,his abiding commitment to environmental protection, the quality of nurturing cultural establishments and innovations and above all his organisational skills and the attribute of connecting with people from all walks of life and all shades of opinion. The Congress, especially in India’s most populace State, needs to impart these attributes to its dwindling cadre. But the moot question is whether there is anyone in the organisational structure who can live up to this task?

An excellent to tribute to the late Congress leader Lakshman Tiwari, worth to read