Dancing To Her Tune

I navigate through the marbled corridors of Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre. Posters of the British production of Life of Pi placed outside the elevator, and other vantage points shout out ‘Winner of 5 Oliviers & 3 Tonys’…’More shows added’. The first show is a few weeks away, but the promotions have been running for a few months. After all, it is a big-ticket event. It is almost certain to be a sellout, additional shows and all. In recent years, many Broadway productions have made their way to Mumbai’s performance spaces. The city has enough deep pockets to guarantee that the seats will be filled – all 2000 at the Grand Theatre in NMACC. And, yes, I will be in one of them.

But, today, I am on my way to a seat in NMACC’s 125-seater black box theatre, the Cube, for a performance by Vijayalakshmi, a top global practitioner of Mohiniyattam, a classical dance form of Kerala. Her mother, Bharati Shivaji, is one of the most well-known exponents of this dance form. Though she forayed into this dance form only at 30, her research and propagation played a significant role in its evolution. Vijayalakshmi gave it a unique edge by adapting it to Tchaikovsky’s ballet composition Swan Lake which she presented with her troupe at the Bolshoi Theatre in 2005.

It has been a while since I attended a classical dance recital, so I wonder what kind of an audience it would attract. A wide range, it appears. Among the twenty-odd people seated are three couples – the women in starched silk sarees and kohled eyes and a few older folk. I am surprised to see a smattering of men who appear to be in their late twenties or early thirties and look like they spend the week behind computer screens in the corporate offices in the BKC area.

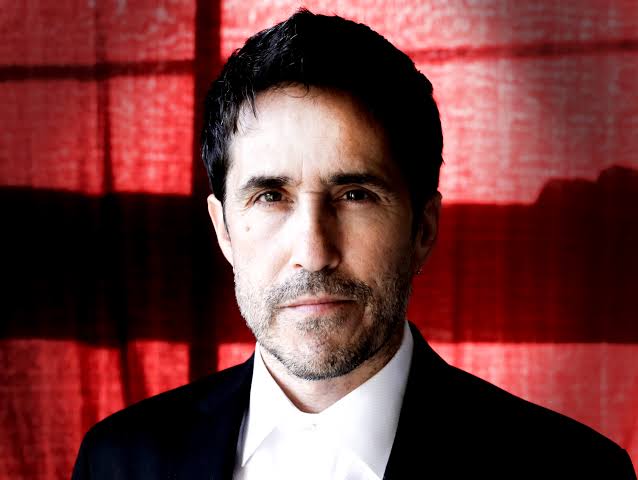

The stage is stark, devoid of props or adornments except for a standing mike on one side. The lights dim, and Vijayalakshmi makes her way to the mic and addresses the audience. A cream and green silk kanjivaram sari is draped in the traditional manner, with one end fanning out at the waist. Chunky gold ornaments glitter on her neck, ears and head. After greeting the audience with folded hands, she talks about the first dance she will perform. It is choreographed on the ashtapadi, hymns from the Gita Govinda composed by poet Jayadeva in the 12th century. She narrates the story of the dance, forming the mudras that will illustrate the story. Her eyes, outlined with thick strokes of kohl, follow her hands. After the brief explanation, she exits into the wings. Her re-entry is to the tune of the melody playing through the speakers. Over the next ten-plus minutes, she glides across the stage as Radha, interacting with an imagined Krishna as she portrays the couple’s first amorous experience. Her face transitions from hesitation to coy to pleasure to ecstasy as the story progresses.

Three more dance sequences follow, each preluded by a short narration accompanied by the gestures that will make up the dance sequence. The second is an excerpt from Ram Charita Manas, and portrays the first meeting of Ram and Sita. The third, my favourite, is set to Tagore’s Mon Mor Megher, with music arranged by Emmy-winning composer Mac Quayle. The song has also been sung by Vijayalakshmi A paean to nature, Vijayalakshmi’s graceful moves and expressive eyes come to gather to create rain that starts with pitter-patter and escalates to a thunderstorm. The last one is set to Carnatic music and portrays dialogue between Shiva and Devi. This is an excerpt from the sound track of the documentary Beyond Grace by LA-based director Sara Baur-Harding. The documentary features four generations of Vijayalakshmi’s family and trails her mother and her as they revisit the people and the places that helped them rekindle interest in Mohiniyattam. All the songs in this sound track were composed by Mac Quayle and sung by Vijayalakshmi.

Throughout the performance, the twenty-something male next to me had been craning his neck every which way so as not to miss a single movement. I assume he is a practitioner of some classical dance form, although in his denims, checked shirt and glasses he looks more like a coder. Well, do you expect him to be in costume in the audience? I chide myself.

But, as it turns out, he is not. A product manager by day, Sayan Choudhary’s interest in learning sign language has brought him to this performance. “My friends who practice classical dance told me that specific movements in the dances represent particular things. For example, I learnt today what symbolises a heart and how different symbols come together to convey a script,” he says.

Vijayalakshmi has agreed to a chat with me after her performance. While I wait for her to finish speaking to those from the audience who have stopped to convey their appreciation, I spot the gentleman who had occupied the seat in front of me. He had been rhythmically bobbing his head with the music through the performance, his off-white semi-ponytail following suit. Many a waah and kya baat had escaped his throat during some wow moments of the performance. I am convinced he is associated with Mohiniyattam. I am wrong.

“I am not associated with any dance,” he says. “My father would take me to classical music shows when I was a kid. I was too scared of him to refuse, and the popcorn was an attraction. But then, I started enjoying it. Later, a friend introduced me to Indian classical dance performances, and it occurred to me that while I had enjoyed the music and vocals, the visuals had been missing. Dance supplied that. It completed the collage.”

I am informed that Vijayalakshmi is ready for me, and I make my way to her dressing room. Much like the stage, this, too, is bare except for a few personal effects. There is no make-up artist, manager or assistant. She has not changed out of her costume, but as we chat, she discards her jewellery and lays it out on the dresser.

As your mother’s daughter, was it predetermined that you would be a dancer?

It was a given. I was five when I had my first photoshoot for Bharatnatyam, with make-up and outfit everything. It felt so natural as if I had some past life connection with dance. I had this compulsive urge to dance, and that’s how it’s always been.

What is your earliest memory of watching your mother dance?

It was in New Delhi at her guru Lalitha Shastri’s house. She was learning Bharatnatyam at that time. I must have been around five and had started learning Bharatnatyam from her guru.

And what made you turn towards Mohiniyattam?

My mother was in her 30s when she turned her attention to Mohiniyattam. I saw the intense research she went into and witnessed her reconstruction of the dance form. She gave it a much-needed new lease of life. My journey with the dance form began at the same time. In a way, as far as Mohiniyattam was concerned, our journeys were parallel. I was only ten, but my mother encouraged me to participate actively. It started small, like holding the curtain in the curtain dance, and then I played a two-minute part in one sequence. My first full-fledged sequence was when I was twelve.

At the start of your performance, you spoke of the world’s interest in Indian art. But, we don’t see the same interest in India. It is challenging to bring in large audiences. As an artist, how difficult is it to perform in a sparse auditorium like today?

Honestly, it is not difficult at all. My daughter asks me how I do it despite the monetary challenges of putting up a performance and the organisational issues. I think it is my unconditional passion for dance that keeps me going. So, the quantity of the audience does not matter; the quality does. It can be a packed hall, but they are disinterested…children are running around, and people are chatting. In one show, a man in the first row was reading a newspaper! But, today’s audience, though small, seemed engaged. I felt the energy was magical.

Yes absolutely. One could see that from people’s reluctance to leave! It was courageous to perform on a bare stage. There were no distractions; all the eyes were on you. There was no scope for a misstep. Is that your usual practice?

Yes, especially when I am performing solo. Then, the onus is on me to keep the audience engrossed. I don’t see the point of having any props on the stage. It is up to me to create the bower in the woods, the palace gardens, and the atmosphere with my presence and spirit.

It was interesting how you introduced each dance with a short narration of the story and some background. Do you always do this?

I think it makes the dance more accessible. The layman does not know what the mudras stand for, so when I familiarise them with what they symbolise, they understand the script of the dance and enjoy it better. It also helps dissipate the divide between the audience and the performer.

I have seen Kathak and Bharatnatyam performances. In both those forms, the feet largely remain flat, and there is some stomping on the floor, whereas Mohiniyattam has pointed toe gliding movements and limp wrists. Is that what prompted you to conceptualise it as an adaptation of Swan Lake?

Yes! The pointed toe is a part of the stance. The feet glide in a serpentine, circular movement. The mayoorapada, or the peacock movement in the ashtapadi performance, is also reminiscent of ballet. In Mohiniyattam, the entire body is involved, which makes it more demanding. Unlike Bharatnatyam, which is more straight line, Mohiniyattam is more languid and slow. Tai chi experts I have worked with in LA equate the movement to Tai chi as the weight is constantly shifting from one leg to the other in both forms. The slow movement is what makes Mohiniyattam therapeutic.

Before you started your performance, you spoke about Mohiniyattam and its role in empowering women. Can you elaborate on that?

You know, women have constantly been suppressing emotions. Men do, too, but for different reasons, maybe because they are told it is not macho to express. But women do it because we believe that our emotions don’t count. So we don’t release them, and this causes disease. The mudras of Mohiniyattam press some points which, over time and with practice, help release stuck emotions. I have worked with women who have suffered from abuse and seen the positive effect of the dance form on them.

Do you think that classical dance form does enough to address contemporary issues?

That is what Mohiniyattam inherently does. When I was creating my first production, I told my mother I did not want to have a damsel for a heroine, thin and weak, pining for her lover. So, for Unniarcha, I found my heroine in the real-life story of a woman who lived more than 350 years ago. She was a feisty woman rooted in traditions and had the strength and resilience to overcome any obstacle. I incorporated Kalaripayattu, the traditional Kerala martial art form, into my choreography. It was the first time it was used with Mohiniyattam. And then, last summer, I collaborated with Oscar-winning composer Yuval Ron and eminent sitar artist Paul Livingston and choreographed Mohiniyattam to ancient spiritual Jewish music. We performed at the Mercardo La Paloma for the marginalised communities of LA. It was an enriching experience.

In these times when the world is riddled with problems, and one is weighed down with the diurnal, do you think art is losing its relevance?

While it may seem challenging to make people see the importance of art in their lives, I don’t think art can ever lose its relevance. Self-expression is most important for every human being. Humans will die if they cannot express themselves, and that’s where art plays a role. It enables us to acknowledge, process and express all that we feel. It will always be relevant.

As I walk towards the exit, stray notes of Tagore’s rain song Mon Mor Megher Songi float through my mind accompanied by the image of Vijayalakshmi’s eyes and hand gestures creating rain, thunder and lightning. Yes, it had been an enjoyable performance, but it had been so much more. Her stories before each sequence and the trivia she had shared had made it a masterclass of sorts on Mohiniyattam and in the space of 75 minutes, I had come away enriched about a topic I knew nothing about. Pi and his tiger peer out at me from one of the posters. Yes, yes, I will catch your show; I roll my eyes at him. But, I will buy a cheaper ticket and spend the money saved on some other shows based on homegrown art forms that I know so little of. It would be my model of CSR – Cultural Social Responsibility.

Wonderful and insightful …this is such a wonderful dance form I wish more n more people discover n get an opportunity to see it…🤗