Somewhere in the North-East

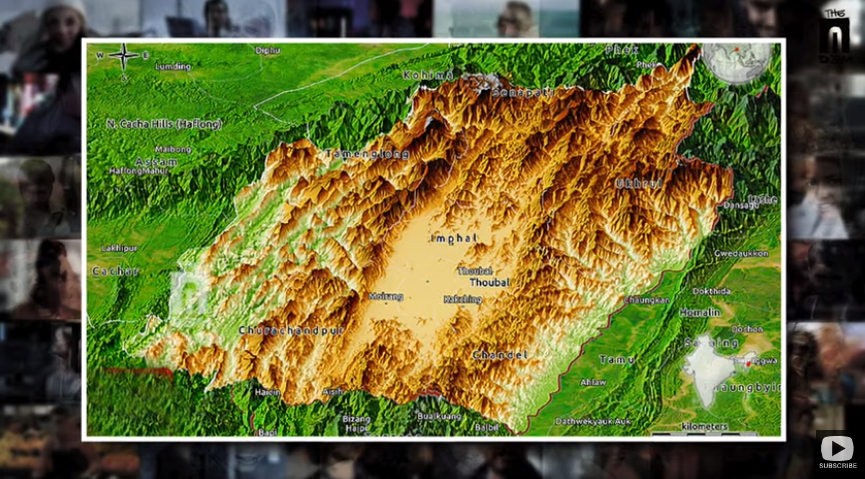

In school, in Geography, we were tested on India’s political map. This required us to know the location, vague outline and capital of each state. I could fairly accurately draw the outlines of almost all the states, but Meghalaya, Tripura, Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur befuddled me. I knew their basic location but switched one with the other. If the exam paper required an outline of any of these five states, I would apply the tried-and-tested eenie meenie miney mo method followed by a quick prayer. I am an 80s student, so the prospect of that one mark in the exam should have been reason enough to commit the geography of that region to memory. But, for a reason I cannot fathom, I did not.

Over the years, I became a keen globetrotter. Every trip was preceded by a study of the region’s geography, rivers and mountains, the location of its cities, and distances. I would spend hours poring over the Atlas and, later, Google Maps. The map of the region would be imprinted in my head so much so that when asked about my itinerary, I would whip out my index finger and air-draw the map of the country and the route. But, the five of those seven sisters continued to stay lumped together in my head as somewhere in the extended eastern arm of the country.

Until last week.

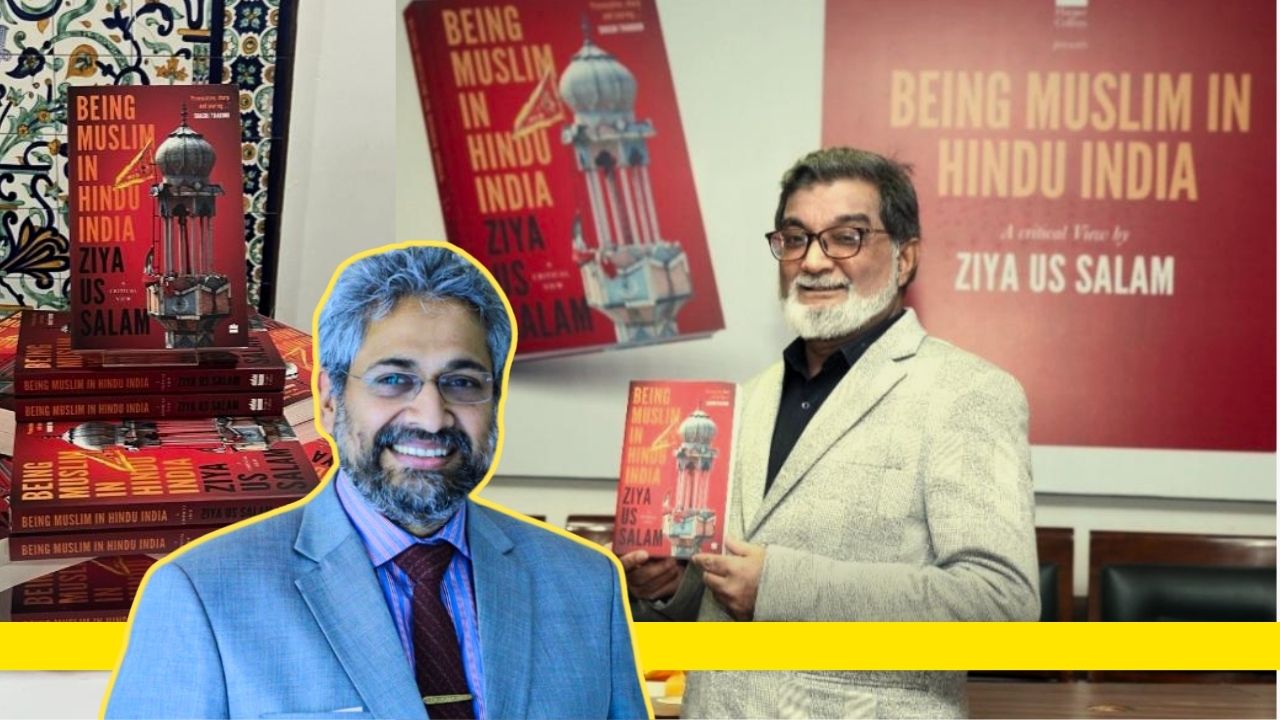

A message from the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) had pinged on my phone. It was about their new publication, titled Peace Eludes Manipur. The description informs that it is a fact-finding report about the ongoing violence in Manipur since 2023. The CSSS team, comprising Director Irfan Engineer and Executive Director Neha Dabhade, had visited the districts of Imphal and Churachandpur in Manipur to gather first-hand data on the situation and the impact on the people and the land.

Over the last year and a half, I have seen articles in mainstream news media on the violent attacks tucked away in between the election news, the U.S. Presidential campaign, endless analysis of wins and losses of the Indian cricket team and other topics that claim our attention. There have also been mentions in my social media feed, but not enough to have stuck. The book’s description sheds reasons on why. One, ‘it has been largely ignored in mainland India’. Two, ‘the complete abdication of the State and Central government’.

I first became aware of CSSS a couple of years ago when I took on a proofreading job of their report on a Citizens’ Tribunal they had conducted. The Tribunal had been conducted along with the South Asia Forum on Freedom of Religion or Belief (SAFFORB), India, to hear cases ofviolations of freedom of religion or belief that took place between 2019 and 2022. The number of instances of communal violence that the Tribunal had heard was shocking, but my ignorance of the incidents was more so. I had considered myself well-informed, so where was the root of this unawareness buried? Was it that these acts were in towns so far-flung away that on my school political map, they would have barely registered as a speck? Or was the number of affected citizens too insignificant in a country racing towards the 1.5 billion mark? Or was it because the headline had not popped out during my quick morning sweep of the daily newspaper?

The report was a revelation. CSSS’ fact-finding report on Manipur Violence promised to be one, too,

What is that foul substance?

Allan Sealy, in his novel Trotternama, asks,

This foul substance is called what?

The foul substance is called history.

Any attempt to make sense of Manipur’s current situation would be half-baked without some throwback into the State’s past. The report starts with a brief history of the region and traces the possible origin of the two sparring sides in the current situation, the Meiteis of the valley and the Kukis of the hills. It then flashes forward to the British era and the role that the Kukis played in India’s fight for freedom. This becomes relevant later as claim and counter claims to origin and belonging are among the root cause of the conflict.

Until 1949, the various indigenous groups and others that inhabited the region coexisted peaacefully. The Meiteis lived in the valley, and the Kukis lived in the hills. They followed their individual lifestyles and customs without impeding the others’.

When India gained Independence, Manipur was designated a sovereign democratic nation with the King as its head and its constitution. India handled its foreign affairs, defence and communications. But, in 1949, the King signed the ascension instrument, and Manipur was merged with India. This did not go down with the people of Manipur, and separatist movements emerged. The Nagas’ demand for autonomy also spilt over into Manipur, where, after Meiteis and Kukis, they are the third largest community in the region. With the unrest refusing to simmer down, the Indian government evoked the Armed Forces (Assam and Manipur) Special Powers Act in 1958. The Act allowed for the use of extreme measures in situations which did not necessarily warranty them. Matters only compounded over the next few decades. Various groups emerged, each with a varying agenda and list of demands. The AFSPA gave the army the free-hand to apply itself in quelling the violence and fear that cloaked the region. This high-handedness came with its own set of troubles.

The history lesson is critical to the report as without a view of the past; it is impossible to see the current scenario with clarity.

The Difficult Child

A few days ago, I met a friend for coffee while her kids, ages 7 and 12, entertained themselves in a playzone next door. Her older kid was giving her trouble. Trouble beyond the odd tantrum or not doing errands. Things had begun to escalate and had started to affect the couple’s marriage. The school suggested counselling and testing for behaviourial disorders. While that process pans out, the child has been placed in the generic group of ‘difficult children’ by teachers, relatives and friends. Meanwhile, the child at the brink of teenhood is fighting for his space and identity while being poked and prodded for reasons he cannot fathom. His problem is specific, but the generic label of ‘difficult’ means that no one quite knows what to do with him.

Manipur reminds me of that kid. The state has been grappling with its identity within the country for decades. This has resulted in numerous skirmishes and conflicts. But, instead of parents and well-meaning parents trying to get to the root of the problem and treat it, it became the hunting ground of political vultures. Be it appeasing various factions or inciting them against each other, the governments that came to power held their interest at the forefront and ignored what Manipur needed. Since 2017, divisive tactics have been at the forefront. Various narratives have been created to feed into the insecurities of both communities. Support for one narrative goes against the rights of the other group and thus builds fear and insecurity. The report chronicles the events that have aggravated the equation between the previously coexisting Meiteis and the Kukis in the last few years.

The simmering tension overflowed when the High Court of Manipur directed the State Government to recommend that the Union government grant Scheduled Tribe Status to the Meiteis. This did not go down well with the Kukis, as it would afford the already-advantaged Meiteis more benefits and allow them to impinge on the rights of the Kukis. To oppose this order by the High Court, the All Tribals Student Association of Manipur (ATSUM) organized a rally in Churachandpur at 10 a.m. on 3rd May.

Reports and witness accounts claim that the Meiteis had begun to preplan an attack on the rally on 2nd May. Like in most outbursts, no one knows who tossed out the first expletive or hurled the first stone. But, the rally turned violent. What followed was finger-pointing and more violent acts. Targeted violent acts. Members of particular communities in specific localities came under attack. Homes were ransacked and burnt to the ground. Churches, mosques and temples were desecrated. Murders. Rapes. Brutality.

As per the official numbers the last fifteen months have claimed more than 220 lives and displaced 70000 people. Refugee camps have been set up at multiple locations. Unofficial guarded borders with checkpoints have been forced within the state to demarcate the land of the Meiteis, the valley, and that of the Kukis, the hills. These borders are as strictly guarded as those between two countries at war. The CSSS team went through intense interrogation and frisking in order to cross through. Kukis and Meiteis, found to be attempting to cross them, have been murdered. The Constitution of India allows its citizens the freedom to move freely throughout the country, but currently, in Manipur, the Kukis must travel eight hours to Aizawl in Mizoram to reach the nearest airport. The border stands as an uncrossable chasm between them and the airport in the valley, which is an hour away.

Manipur violence is among the most unprecedented conflict in India and has placed the state in a war-like situation. Yet, the report states that there has been no constructive move by the State or the Central government. The only steps that have been taken target the Kukis and pacify the Meiteis. This further boosts the narrative propagated by the Meiteis and adds to the fear amongst the Kukis. Thus, the pot refuses to simmer down. And the fear of boiling point is very real.

Restoration of pece to this region lies firmly with the state. A political solution is the only means to start the treatment of the decimated-Manipur and its wounded people. But, no healing can emerge from apathy. And, this reader can only hope that CSSS’ report will create enough noise to drum up support that will prompt action to bring peace to Manipur.

Too optimistic? Perhaps.

But, it did prompt this reader to commit to memory its location on the Indian map without the incentive of an additional mark in the geography exam.

So, there may be hope after all.

To read the excerpt from the CSSS report, Click Here