Why Tamil Nadu Resists Three Language Policy in Education?

The National Education Policy, 2020 has mandated that all school children in India should learn their mother tongue, English and another Indian language. Recently certain grants of the Union Government under a special scheme to reach out all children, Samagra Siksha Abhiyan, for the state of Tamil Nadu have been withheld since the state has not acceded to the implementation of the NEP. When the Union education minister plainly stated this as the reason for non-disbursal of grants, the public sphere in Tamil Nadu saw an eruption in unison to protest against such strong-arm tactics to interfere with the right of the state to follow its own education policy and the perceived imposition of Hindi.

The state has several significant points of disagreement with NEP 2020, a policy it had no role in drafting. However, the most notable among them is its strong opposition to the so-called three-language formula in school education. In January 1968, Tamil Nadu’s state assembly passed a resolution that the state education board would adhere to a “two language formula” and teach only Tamil and English in Government schools, following the relentless protests against the imposition of Hindi that reverberated throughout the state from 1964-65.

It is important to note that while there were many spells of anti-Hindi imposition protests in Tamil Nadu, two significant ones occurred in 1938–40 and 1965, consolidating the Dravidian movement and eventually bringing the DMK to power. The first was in 1938-40, when C. Rajagopalachari then premier of Madras Presidency following the provincial elections under the Government of India Act 1935, sought to make Hindi a compulsory subject in schools, so that eventually Hindi could be made national language or at least the sole official language of the country. This resulted in forging a Dravidian consensus by uniting all hues of Tamil scholars and enthusiasts with Non-Brahmin Self-Respecters. With the onset of the second world war and resignation of the Congress ministry, the Hindi imposition in schools was stopped.

The second phase of the violent protests in 1964-65 that involved extreme acts of self-immolation of several activists and concomitant arson, public unrest, and the death of several people in police and military firing were not against making Hindi a compulsory subject in the schools, but against Hindi becoming the sole official language of the Union Government. After the virulent protests, the Congress ministry, led by Lal Bahadur Sastry, vowed to uphold Nehru’s assurance that English would also remain the official language of the Union Government in addition to Hindi until all states of the Union adopt Hindi as the sole official language. Since Tamil Nadu felt that it would become an unequal member of the Union if Hindi is made the sole official language, its injunction against the possibility was to resolve not to teach Hindi as a subject in the Government run schools of Tamil Nadu. This history makes it clear that teaching Hindi in the Government Schools in Tamil Nadu is closely linked to the proposal that one day Hindi would become the sole official language of the Union Government.

The Ruse of Three Language Policy

It is in this context, the New Education Policy’s gambit to mandate the study of three languages without specifying Hindi as the third language to be studied in Tamil Nadu should be viewed. Now, what should the students studying in the 37,554 government schools in Tamil Nadu learn as a third language? Let us address this question first. The State Education Board is presently administering the 12th standard examination to an estimated one million students. The overwhelming majority of Government School students, who come from a working-class background and lack what sociologists refer to as “cultural capital,” already encounter difficulty in learning two languages, Tamil and English, as well as Mathematics, Science, and Social Science. It has been a significant challenge to prevent attrition and guarantee that all students complete their school education. The continuation of school education for the most vulnerable sections of society has been made feasible through the implementation of programmes like the noon meal scheme and the provision of a free nutritious breakfast.

Education policy makers speak of an abstract universal cognitive ability of children to learn languages. Any cursory knowledge of the workings of the Government Schools will make clear the formidable challenges that teachers face bridging the cultural divide that separates the elite and the subaltern. The syllabi need to meet some universal standard while also remaining accessible to the students from disadvantaged sections whose everyday life remains alien to the imperatives of the knowledge acquisition process. The touting of the abstract cognitive ability of “children” as a universal category to learn languages totally fails to address the inadequacy in everyday resources and cultural capital that subaltern classes suffer from. It is absolutely ironic that the proponents of the third language call it “an opportunity” for the students of Government Schools to be asked to learn an additional language. Anyone who is involved in the processes on the ground would describe it as an unjustifiable burden that impedes education.

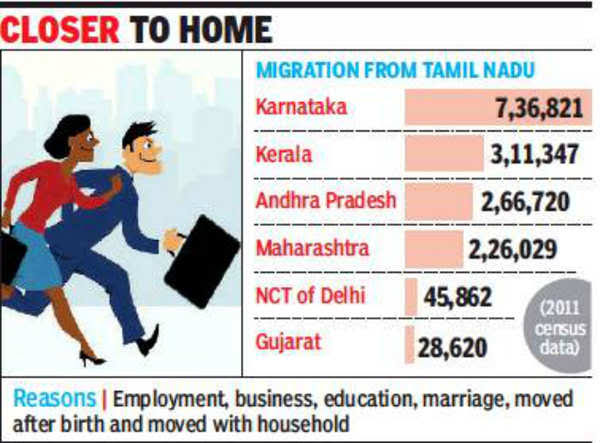

There is an even more pertinent dimension to the “additional language as an enhanced ability” proposition. In the past fifty years, people from Tamil Nadu who have relocated to various regions of India have encountered no challenges in acquiring the necessary language skills to perform their duties, whether in Bombay, Bhuvaneshwar, or any other location in the Northern or Southern states. Language never impedes labour migration or entrepreneurial contacts, as evidenced by the growing number of migrant labourers from the North in Tamil Nadu. In the case of managerial positions either in the corporate sector or public sector, there has hardly been any reports of language coming in the way of performance of the people from Tamil Nadu in other states, whether Karnataka or Andhra Pradesh or Orissa. This is because acquiring everyday communication skills has nothing to do with learning a language in school. Moreover, the majority of Tamil Nadu’s managerial class employees possess superior English language skills, which are essential for conducting business in the majority of cases

It is in this context that people wonder what could possibly be the third language that school students could beneficially acquire in Tamil Nadu. Is there any Indian state that offers them abundant career opportunities that mandates learning of the language of that state? For example, a significant number of people go to work in the Gulf states which should recommend learning Arabic.

Actually, with the population size that exceeds most European countries and with a thriving economy, there is hardly any need for most of the economically vulnerable sections to leave the state to make a living elsewhere, as the influx of migrant labour from North to Tamil Nadu clearly demonstrates. Hence, the argument that learning an additional Indian language is helpful rests on thin ice. If one thinks of training and equipping tens of thousands of qualified teachers to teach “Indian Languages” in the government schools, the true scope of the problem becomes apparent. It is obvious the enigmatic third Indian language will turn out to be Hindi, the only language that can supply enough teachers. Furthermore, once teaching a third language is mandated, even from the perspective of the people, Hindi would become the preferred choice since it is the language of the media in the north which spills into Tamil Nadu. Once Hindi is taught in Tamil Nadu Government Schools as a mandatory third language, naturally the resistance to Hindi becoming the sole official language of the Union would weaken. The hegemonic assertion of Hindi will result in the progressive decline of Tamil once it becomes the official language of the Union and the link language within India. These are not unfounded fears as they germinate from the long durée history of Tamil Nadu as we shall see.

The Questions that Tamils Ask

It will be easy to convince Tamils if the North Indian states or other South Indian states can demonstrate the positive impact of the three-language formula on their socio-economic development over the past fifty years. The aspiring public in Tamil Nadu will surely insist on the third language if the benefits are so demonstrated, despite whatever the political parties say. The problem is there is no such demonstrable data or observable outcome to support three language policy adopted in other states. An analysis published recently clearly states that most parts of North Indian states are monolingual. Moreover, if the NEP encourages the medium of instruction to be in the ‘mother tongue’, it begs the question whether Hindi is the mother tongue of a Mythili or Bhojpuri speaker and how many schools have Mythili or Bhojpuri as the medium of instruction. This is not a rhetorical question since Tamil Nadu fears that Tamil may be pushed to a vernacular secondary status and finally made a local dialect like Bhojpuri, if the camel of Hindi language is allowed into the tent. There is a long durée historical reason for this fear in the form of Sanskritic and Brahmin hegemony. This needs some parsing.

In all the so-called agamic temples in Tamil Nadu, a land blessed with so many architecturally rich and well-endowed temples, the archana or prayers in the sanctum sanctorum, the Garbha Graha, was performed only in Sanskrit making it the sole language of the Gods. It was not until the DMK’s rule in Tamil Nadu that it was required that the prayer be recited in Tamil, if the devotee so desired. In the late Middle Ages, Tamil was infused with Sanskritic terms and expressions giving rise to a hybrid formation called Manipravalam. All this also meant Brahmin hegemony in the socio-political sphere with its attendant perpetuation of caste hierarchy. Tamil Saivism and Tamil Vaishnavism were at the forefront of the resistance movement against the hegemony of Sanskrit and Brahmanism for the past millennia, dating back to the Bhakti movement and Ramanuja. In particular, the neo-Saivite movement of the nineteenth century gave rise to the Thanithamizh, or Pure Tamil movement, which aimed to revive the use of Tamil’s original root words by replacing Sanskrit-derived expressions. At the turn of the 20th century, the neo-Buddhist, Dalit movement of Iyothee Thoss also performed a similar restoration of Tamil antiquity as Buddhist antiquity by offering a different gloss to terms and expressions in Tamil. Taking this long durée prehistory into account, it should be clear as daylight that resistance to Sanskrit infusion is inseparable from resistance to Brahmin hegemony which pervaded the early modern public sphere in Tamil Nadu. It took a massive and concerted effort in the early twentieth century to constitute the Tamil public sphere without the hegemonic inscriptions of Sanskrit/Brahminical Hinduism, even as the process formed the foundational template of democratic mobilization and subaltern assertion in Tamil Nadu.

For all this non-Brahmin Tamil identity consolidation in politics, Tamil Nadu has remained fully integrated to the historical journey of the Indian republic and has articulated Indian nationalism powerfully. It has a vibrant and thriving non-Brahmin subaltern practices of piety that Brahminical Hinduism is unable to subsume. There has been no dearth of participation in the military, in the Indian Administrative Service, in media and sports or in the broader economic sphere. It is through progressive democratization and cultivation of a strong regional identity, that Tamil Nadu has contributed to the developmental goals of the Indian Union. It accepts Mahendra Singh Dhoni as “Thala” (leader of the IPL franchise Chennai Super Kings) and receives migrant labour from Bihar and North East with comfort and warmth. During events such as the India-China or India-Pakistan conflicts, as well as the most recent Kargil war, Tamil Nadu’s patriotic fervour was on full display, solidifying its place in the Indian journey. It presents the Union government with the most critical and stark question: would it be prudent to maintain English as the official language of the Union to foster the development of robust regional identities and their integration into India, or to establish Hindi as the sole official language of the Union, thereby sowing the seeds of dissent and alienation? The three-language policy in education is just a foil to the basic question.

Once Hindi is taught in Tamil Nadu CBSE schools as a third language, naturally the resistance to Hindi becoming the sole official language of the Union would weaken. The hegemonic assertion of Hindi will result in the progressive decline of Tamil once it becomes the official language of the Union and the link language within India. These are not unfounded fears as they germinate from the long durée history of Tamil Nadu as we shall see. …. So I request the authors to raise their voice against imposition of Hindi through CBSE and private schools in TN.

Languages are taught as SUBJECTS in schools. Listening, speaking and Reading must precede writing. Phonics are the essence of any Language. All Indian Languages are phonetic. Writing TAKES THE FRONT SEAT IN OUR SCHOOLS, ESP TN GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS. That’s why even Tamizh misses out

Actually there’s no resistance to hindi at the ground level from the public. More than half of the students study in CBSE schools where three language formula is followed. The truth is like opposition to NEET which is causing loss of crores of rupees to DMK criminals who own medical colleges, these private CBSE schools where hindi is taught are owned by the same DMK CRIMINALS Hence this shouting in parliament