I have not experienced the trauma of Partition directly. The partition story I discovered through archival research, was a memorable Odia tale called, ‘They Too are Humans’ by an obscure author named Sushila Devi. Such creative work in the province has not been many: Odisha, is not a frontier province.

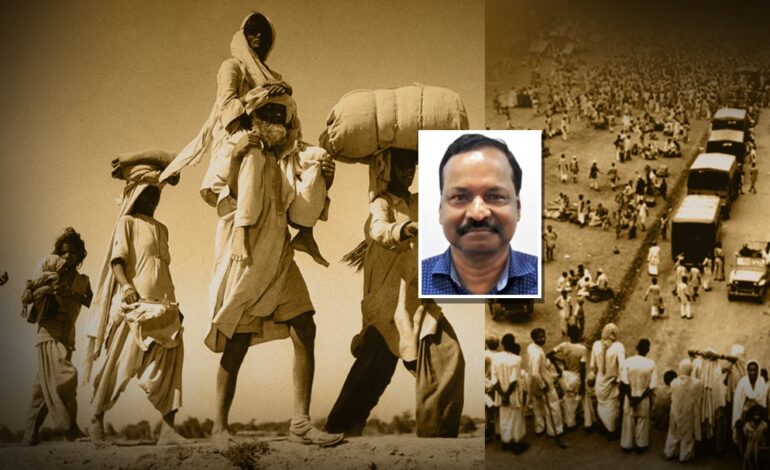

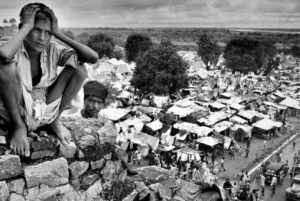

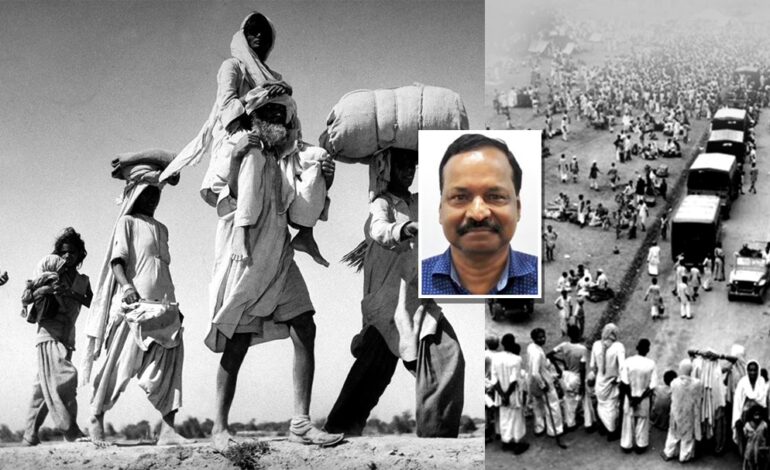

While Partition does not seem to have left a deep impression on the Odia psyche, the consequences of Partition have been visited upon the State, many times over, through streams of refugees that arrived in the State from East Bengal, and later Bangladesh, during the Fifties and Sixties of the last century. Train loads of victims settled in colonies numerically named, by an impersonal bureaucracy, concealing the sense of agony and angst. Such colonies still stand in the Dandakaranya region of Koraput, Malkangiri, the neighboring Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh.

I had been to one such colony that lay in a state of poverty, neglect and squalor, when I worked in Koraput. Geographically distant from centers of power, such refugee colonies, caught in a historical time warp, are perennial reminders of our troubled national past. The inhabitants are irresistibly haunted by what the postcolonial critic Dipesh Chakrabarty calls ‘sentiments of nostalgia’ and the ‘sense of trauma,’ nostalgia for the land left behind, and trauma for the agony undergone in the act of displacement.

As in the case of individual misfortunes, nations often wonder as to why such calamities had to happen? Could they have been avoided? Could we have saved Hiroshima and Nagasaki from nuclear disaster? Were there alternatives available? How do we deal with memories of the Indian Partition? How do we make atonements for historical wrongs? How shall we go beyond symbols, rituals and memorials of the stereotypical kind, enacted periodically on both sides of the border? Could lasting answers be found by Track 11 diplomacy alone?

Certainly, 75 years after The partition holocaust we are wiser on many counts. Although The partition caused an immense catastrophe, it was by no means the only one of its kind the world over. The partitionof Germany in general, and Berlin in particular, of the two Koreas, the conflict between the Union and confederacy during the cataclysmic Civil War in America, all took their toll in the lives of millions of people. While some issues have been solved through military means, or through means of conciliation and understanding, others, as in India, have continued as festering wounds that manifest through periodical conflicts and conflagrations : 1948, 1965, 1971 and the Kargil War. Indeed, today, the entire South Asia, from Afghanistan, through Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Maldives is a perpetual conflict zone.

Material Memory

While political pundits try and find answers to crises in the subcontinent, and historians grapple with the many causes of the Partition, it is in the realm of literature, culture, research, and documentation, what critics in recent years, have called ‘Material Memory’ that lasting answers could be found. We can then hope to go beyond the world of grief, pain and suffering. Listing, cataloguing and memorializing, as in the Holocaust museums of Jerusalem, would be one significant way we could begin the process of healing and pay homage to the unnamed victims of the Indian Partition.

There are of course those who caution us not to return to the past lest we open the festering wounds. But then, the ghosts of the past refuse to go away, as we have painfully seen in annals of cruelty.

Tulsa Massacre and ‘Black Lives Matter’ Movement

The models in this context are not entirely absent. There have been sustained efforts in the U.S., for instance, to make reparations during the Centenary of the Tulsa massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 2020. The Centenary of this event coincided with contemporary Black Lives Matter Movement.

In 1920, in the Tulsa county of Oklahoma, hundreds of innocent Blacks were massacred, many machine-gunned from the air, on account of the unfounded allegation of rape of a young white woman, Sarah Page, by a black lift- operator, Dick Rowland. American critic, Leslie Fiedler’s notion of the threat of interracial rape comes to our mind here. As it turned out, after a legacy of race crime and white supremacy of Ku Klux Klan, and racist cinema like ‘The Birth of a Nation’ by D W. Griffith, the American nation has attempted to deal with the question of crime and punishment, just as the German Chancellor Willy Brand went down on his knees to offer apology for the German complicity in the Holocaust caused by the Nazis. Similarly, the Japanese Government, in recent years, has made war reparations to the Korean ‘comfort women’ who were conscripted to cater to the sexual needs of the occupation army in South East Asia and the Far East.

Sadly no such gesture of apology and atonement has been forthcoming from the conflicting parties in the subcontinent. A neutral account would see guilt and culpability in many quarters – political, military, colonial, nationalist, and civic; it would indict the so called custodians as well, the police, military and civic authorities, those who were meant to protect but looked the other way and abandoned their posts in times of need.

And yet, we must cherish and uphold the many gains achieved: the study of partition narratives, the plight of children and women recorded, on both sides of the border through the pioneering work of critics like Urvashi Butalia and others, or the gains in understanding we have made through the study of ‘Material Memory’, of a brooch, a shawl, an insignia, an emblem left behind by the victims of the Partition. Each object as archivist- critic, Anchal Malhotra brilliantly shows, becomes a storehouse of remembrances for successive generations. It is a perpetual reminder of guilt and the need for expiation, both sacred and secular.

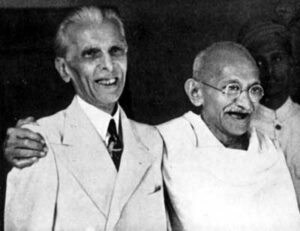

Finally, to my mind, the folly and absurdity of partition comes through a richly layered arabesque of ironies. The suit-clad pipe smoking Mohammed Ali Jinnah, suffering from terminal cancer, who becomes the apostle of a theocratic state, an unlikely candidate for such a purpose, if there was one. His conversations with his sister Fatima in the winter of 1948 are a far cry from the earlier note of triumphalism, as we read in the excellent biography of the founder of Pakistan called Jinnah of Pakistan by Stanley Wolpert.

We must deeply ponder over the irony. Jinnah unveiled the contours of a secular state in the Pakistan Constituent Assembly, his address and rhetoric, diametrically opposite to the earlier discourse of a carefully crafted creation of Pakistan as the ‘land of the pure’. Heralded as ‘Quaid e Azam’ in the new State, he declared in Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly on 11 August 1947:

‘…Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal, and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.

He went on, perhaps captivated and carried away by the strength of his own liberal argument, quite unmindful of the effect it was having on the audience that perhaps expected a rationale for the creation of an Islamic state :

‘Now what shall we do? Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous, we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and especially of the masses and the poor. If you will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that every one of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste, or creed, is first, second, and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges, and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make.’

Jinnah’s sister Fatima lived long enough in Pakistan till 1967 to see the Army take over; she must have realized the folly of her brother’s action in the creation of Pakistan.

Journey to Islamabad

The strangeness of The partitionstruck me when I was invited to visit Pakistan on an academic assignment. I travelled in a circuitous manner via Dubai. [There was then no direct flight to Pakistan then] My hosts in the Islamabad Club, undeterred by the Pakistani Army, the ISI and the ‘deep state,’ welcomed me exultantly in Islamabad and said, ‘Welcome our friend from India’. They let me savor the choicest Punjabi food and the best of Mohammed Rafi.

Later, a group of students at the conference hotel accosted me. ‘We want to go to India!’ they said in a chorus, their leader, a petite bespectacled girl. “I am Fiza” she said, ‘you remember the Hindi film Fiza. Well, that’s my name too!’

I promised to help when I got back and share the message of goodwill I had just received through the Hotel’s email. Fiza’s glass-painted picture frame hangs in my study till date.

A group from the University of Modern Languages, Islamabad posed for photographs at the hotel lobby and passed on their messages with their email id to be shared with my students in Hyderabad.

At the Karachi stop-over, [on my back to India] in the Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flight, the hotel manager was happy to meet me. ‘I have a doctor brother in Moradabad’, he said enthusiastically, just as the Custom’s Officer at Karachi airport reminisced nostalgically about his father’s origin in North India.

Did I fall in love with our ‘enemies’? Was this what some call the Stockholm syndrome, the classic case when one is charmed by one’s adversary/captor?

Chittagong 1998

On a trip to Bangladesh in 1998, I was welcomed to the historic Chittagong Club by Robert Kadir, one time friend of the Indian communist, Mohit Sen whom I had met in Hyderabad before he passed way. I had travelled to trace the footsteps of the legendary Surya Sen and Kalpana Dutta of the famous Chittagong Armory Raid

It was worth recalling the local history: After the Pakistan Constituent Assembly’s address on 11 August 1947, offered in the best manner of a liberal ideologue, Mohammed Ali Jinnah made a radical volte face in Dhaka and gave a clarion for Urdu supremacy in the Bengali majority East Pakistan , a fatal move that led to the independence of the breakaway province in 1971.

Addressing the students of Dhaka University, in 1948, Jinnah declared firmly:

‘Let me restate my views on the question of a state language for Pakistan. For official use in this province, the people of the province can choose any language they wish…

There can, however, be one lingua franca, that is, the language for inter-communication between the various provinces of the state, and that language should be Urdu and cannot be any other…

The state language, therefore, must obviously be Urdu, a language that has been nurtured by a hundred million Muslims of this sub-continent, a language understood throughout the length and breadth of Pakistan and, above all, a language which, more than any other provincial language, embodies the best that is in Islamic culture and Muslim tradition and is nearest to the languages used in other Islamic countries …

These facts are fully known to the people who are trying to exploit the language controversy in order to stir up trouble. There was no justification for agitation, but it did not suit their purpose to admit this.

Their sole object in exploiting this controversy is to create a split among the Muslims of this state, as indeed they have made no secret of their efforts to incite hatred against non-Bengali Mussulmans …

Make no mistake about it. There can be only one state language if the component parts of this state are to march forward in unison and that language, in my opinion, can only be Urdu.

I have spoken at some length on this subject so as to warn you of the kind of tactics adopted by the enemies of Pakistan and certain opportunist politicians to try to disrupt this state or to discredit this government.

The Virtue of Atonement

What then are the lasting lessons? It’s time we made fresh beginnings. Material memories bring remorse and atonement; they pave way for the spirit of dialogue and understanding, within the nation-states and across the borders, perhaps unveiling new chapters in nationhood. We need to go beyond blame games and revenge history, the religious divides of the Manichean kind. We must pay attention to the cultural fault lines and seismic zones within our own body politic; we must extinguish the flames over language, ethnicity and nationality, and thereby help create a new South Asia for the future generation.

Excellent piece. Looking forward to more such article.It touched my heart.