Where to Find the Ecologist in Marx?

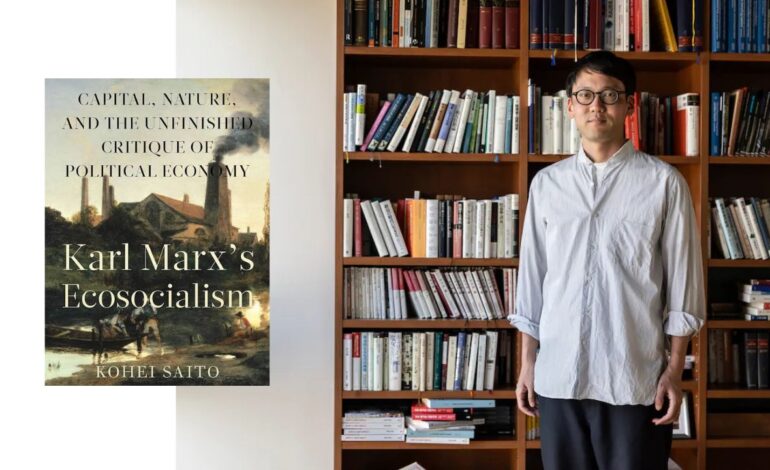

A Reading of Kohei Saito’s Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism – Part 1

As one delves into Kohei Saito’s book—a meticulous examination of Marx’s critique of capitalist production in the age of global ecological crisis—an old political cartoon, published over a century ago in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (USA), comes to mind. This 1911 illustration, titled DEE-LIGHTED, depicts a festively adorned Wall Street welcoming Karl Marx with open arms. The bearded revolutionary stands among America’s corporate elites, clutching a copy of Das Kapital. Among those enthusiastically greeting him are John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, George W. Perkins, and even Progressive Party leader Theodore Roosevelt.

The cartoon’s creator, Robert Minor, was himself a socialist, later joining the Communist Party. But what prompted him, a staunch communist, to imagine a world where Wall Street embraced Marx?

Adding to this puzzle is a letter from William Lawrence Saunders—chairman of Ingersoll-Rand Corporation and deputy chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York—to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson on October 17, 1818. In this letter, Saunders writes:

“Dear Mr. President: I am in sympathy with the Soviet form of government as that best suited for the Russian people…”

(Quoted from Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution, Antony C. Sutton, 1971.)

Why would a titan of American corporate capitalism express such an affinity for the Soviet system?

A crucial piece of this historical puzzle emerges in Lenin’s speech at the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party on March 15, 1921. Reflecting on the economic devastation of post-revolution Russia, Lenin makes a stark admission:

“The rule of the proletariat cannot be maintained in a country laid waste as no country has ever been before—a country where the vast majority are peasants who are equally ruined—without the help of capital, for which, of course, exorbitant interest will be extorted. This we must understand. Hence, the choice is between economic relations of this type and nothing at all.”

The post-revolution Soviet state, as history shows, found itself entangled in the very economic forces it sought to overthrow, relying heavily on Western capital and technology to rebuild its industries.

Examining these three historical threads—the cartoon, the corporate endorsement of Soviet governance, and Lenin’s pragmatic concessions—within the context of today’s economic and environmental crises reveals a persistent tension within leftist thought. The centralized structures of power and an unwavering faith in technological advancement, often celebrated by traditional Marxists, have played a crucial role in shaping economic policies. But have they also inadvertently sabotaged the political agency of the working masses?

Marxists, historically, have been ardent advocates of technological progress, arguing that only through the continuous development of productive forces can capitalism be transcended. But to what extent did Marx himself critique the emancipatory potential of technology under capitalism? This is precisely the question Saito seeks to answer.

Modern ecological Marxists argue that capitalism itself is the driving force behind environmental degradation. Yet, many of them still uphold an unshaken faith in technological solutions. Consider Herbert Marcuse’s optimistic vision:

“There is an opportunity to transform quantitative technological progress into qualitatively different ways of living—because this would be a revolution occurring at a higher level of material and intellectual development. It would enable humanity to overcome scarcity and poverty. If this radical transformation is to be more than a passive utopian dream, it must be rooted in the very structure of modern industrial production, its technological capabilities, and their application. Freedom depends, unavoidably, on technological progress.”

(Marcuse, 1969: 19)

To this, Saito offers a sharp rebuttal:

“Unfortunately, the Promethean Marxist dream of achieving freedom through technological progress has never materialized. Instead, ‘progress’ has manifested as an unchecked, destructive force upon the planet.”

In the face of escalating environmental crises, ecomodernist visions—proclaiming that technology alone can solve climate change—continue to hold sway. Despite a history of failures, such techno-optimistic ideologies wield considerable influence over contemporary politics.

Saito scrutinizes the responses of contemporary Marxists to this dilemma. He points out, for example, how Alberto Toscano (2011) argues that the left must reclaim ‘Promethean’ ideals to construct a post-capitalist world. Similarly, he critiques Aaron Bastani’s vision of Luxury Communism, which exudes Promethean confidence:

“Our desires must be Promethean, for our technology has already made us gods—so let us do it well.”

(Bastani, 2019: 189)

For many contemporary Marxists, the rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) represents an unprecedented opportunity to automate production and render traditional labor obsolete. Yet, as Saito warns, such utopian visions often ignore the massive unemployment and social upheaval these very technologies can unleash.

Saito’s most striking argument, however, is that late Marx himself became increasingly critical of the liberatory potential of capitalist technological development. While the Grundrisse is often cited by Promethean Marxists as evidence that Marx saw industrial progress as a stepping stone to socialism, Saito contends that Marx’s later works reveal a more cautious, even skeptical, perspective.

Thus, Saito argues, if one seeks the true foundations of a Marxist ecological critique, they are not to be found in the Grundrisse of the late 1850s but rather in Marx’s later writings—where he revises and deepens his earlier insights.

In an era where capitalism’s expansion threatens planetary survival, Saito’s work challenges us to reconsider the meaning of progress itself. Can socialism be reimagined beyond the Promethean faith in technology? Or does the pathway beyond capitalism demand not only economic transformation but an entirely new relationship with nature?

Subsumption – Formal and Real

“The concepts of ‘productive force of capital’ and ‘real subsumption’ that Marx expanded upon in the 1860s serve as indications that he had distanced himself from the ‘productionist conception of history’ that lingered in Grundrisse. This theoretical development holds great significance in reconstructing a non-Promethean Marx. The absence of the discussion on ‘co-operation’ in Grundrisse, which later appears in Capital, reflects this shift. Consequently, Marx was compelled to raise doubts about the progressive nature of the development of productive forces. Nevertheless, these three concepts—real subsumption, productive force of capital, and cooperation—introduce certain tensions within his earlier materialist conception of history. Since contemporary utopian socialists find Marx’s theoretical shift in the 1860s unacceptable, they inevitably retreat to his Prometheanism of the 1850s.”

By successfully integrating the material transformation and reorganization of the labour process into the theory of ‘real subsumption,’ Marx was able to develop his analysis of the capitalist mode of production in a manner consistent with his methodological dualism, as argued by Seito.

In the 1860s, as Marx consciously distanced himself from his earlier ‘technocratic productivism,’ he was compelled to rethink his optimistic view of history and engage more seriously with its negative repercussions.

This self-critical transformation became possible when Marx examined how the material dimension of the capitalist production process—specifically, the physical world, both human and non-human—was reorganized under capital’s hegemony to serve its own accumulation. He realized that the growth of productive forces facilitated the subjugation of workers to capital’s command more effectively. If this was the case, then the simple dichotomy between ‘relations of production’ and ‘productive forces,’ as traditionally assumed in historical materialism, was no longer tenable.

In Capital, the development of productive forces under capitalism hinges on a comprehensive reorganization of humanity’s metabolism with nature in the form of cooperation, division of labour, and machinery. In this sense, the material components of production are embedded within a specific social configuration, which is expressed in the ‘mode of production.’ This is why, in the introduction to Capital, instead of treating ‘productive forces’ as an independent variable, Marx assumes the responsibility of analysing ‘the capitalist mode of production and the relations of production corresponding to it.’

Seito, citing Andre Gorz, explains that figures like Gorz successfully grasped Marx’s realization: ‘Technologies, relations of production, and the nature of commodities not only shape the length and equality of consumption satisfaction but also eliminate the stability of social production itself. Hence, the development of productive forces within capitalism will never lead to the gateway of communism’ (Gorz, 2018, 110-11). The concept of ‘real subsumption’ thus represents a radical shift in Marx’s assessment of capitalism’s progressive character, which is why, in Capital, he ultimately refrains from endorsing its progressivism, as Seito argues.

Marx repeatedly warns that the development of productive forces under capitalism disrupts and devastates the universal metabolism of nature. As long as the capitalist mode of production is governed by the logic of valorization, the reorganization of the material aspects of the labour process degrades the material conditions of collective production. ‘It is not only the worker who is plundered but also the soil’ (Capital 1: 638). Therefore, as Marx states in Capital Volume 3, ‘future society must regulate humanity’s metabolism with nature in a rational manner’ (Capital 3: 959). It becomes clear that capitalist development of productive forces does not create the conditions for sustainable control over humanity’s metabolism with nature. In other words, even if capitalism surpasses its inherent limits and transcends the constraints on productive force development, capitalist technologies remain both unsustainable and destructive. Even a socialist system cannot deploy them in a genuinely sustainable manner.

This issue lies at the heart of how Marx conceptualizes the establishment of capitalism. In the chapter on ‘primitive accumulation,’ he points out that real capitalist accumulation only occurs on the foundation of productive forces that have emerged under capital’s hegemony. Capital initially appropriates existing labour processes—technologies, markets, means of production, and workers. Marx refers to this phase as ‘formal subsumption.’ Under this framework, the labour process continues as before, but by monopolizing means of production and consequently proletarianizing workers, capitalists force workers into wage labour while accumulating capital through existing markets.

Yet, capitalism cannot expand indefinitely on the basis of existing productive forces. The preconditions for a truly capitalist labour process can only be created by capital itself. Thus, until capital fully integrates the social relations and labour practices that align with its imperatives, it gradually restructures them, leading to the complete subjugation of the labour process under capital. This is how Marx resolves the paradox that only capital can create the conditions necessary for capitalist production. Marx refers to this transformation as ‘real subsumption.’

(To be continued…)

Translated from Malayalam by Sania KJ.