Harmony or Hype? The Biodiversity Crisis on Our Watch

Today marks the International Day for Biological Diversity (IDB), a United Nations-sanctioned event tied to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The 2025 theme, “Harmony with Nature and Sustainable Development,” emphasizes the interconnectedness of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), urging collective action for a sustainable future. Yet, in biodiverse nations like India, turning this vision into reality is fraught with systemic hurdles.

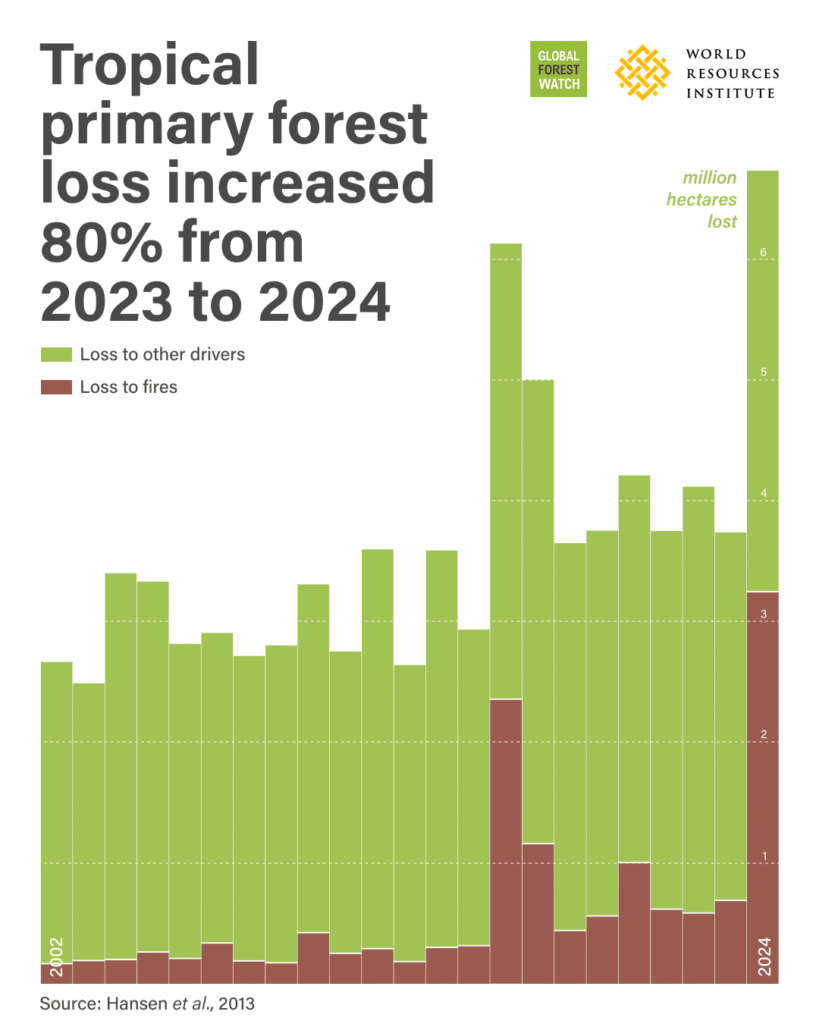

Biodiversity—plants, animals, microorganisms, and their ecosystems—sustains humanity. Plants fuel 80% of global diets, fish provide 20% of protein for 3 billion people, and 80% of rural healthcare in developing nations relies on plant-based medicines. However, the 2019 IPBES report warns that 1 million species face extinction, with 75% of terrestrial ecosystems degraded by deforestation, pollution, and climate change. India, hosting 7-8% of global species, lost 2.33 million hectares of forest cover between 2001 and 2023, per Global Forest Watch, driven by agriculture, mining, and urban sprawl.

The KMGBF’s 23 targets for 2030, including restoring 20% of degraded ecosystems and halving invasive species, align with SDGs like Zero Hunger (SDG 2) and Life on Land (SDG 15). But India’s efforts falter. Weak enforcement permits illegal sand mining and quarrying in the Western Ghats, where 2024 data reported a 12% decline in endemic plant species. The National Biodiversity Authority’s 2024 budget of ₹143 crore is dwarfed by the $700 billion global funding gap noted by the World Economic Forum, with private investment nearly absent.

Kerala, a biodiversity leader, shows both promise and pitfalls. It was the first Indian state to implement People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs) under the Biological Diversity Act, 2002, documenting local species and traditional knowledge via community efforts. In March 2025, Kerala launched its second PBR batch, updating records for ecosystems like the Silent Valley National Park. Yet, a 2024 Kerala State Biodiversity Board report found 35% of PBRs outdated due to inadequate training and local disengagement. Species like the Nilgiri tahr, with only 2,400 left, face habitat loss from tourism and coffee plantations. The Vizhinjam port project, linked to a 15% drop in local coral cover per 2024 studies, highlights development’s toll on biodiversity.

Globally, IDB 2025, backed by the CBD Secretariat, pushes for action. The IPBES’s 2024 Transformative Change Report, presented in Geneva, outlines systemic fixes, but India’s bureaucratic gridlock slows progress. Social media campaigns with #BiodiversityDay and #KMGBF raise awareness, yet policy impact lags. UNESCO’s biosphere reserves, spanning 6% of Earth’s land, and Denmark’s 2024 Green Tripartite Agreement, blending emission taxes with peatland restoration, offer models India struggles to adopt.

With five years to meet 2030 targets, the stakes are high. Globally, 25% of assessed species are threatened, per the IUCN, and 41% of amphibians face extinction. The $700 billion funding gap persists, with only $200 billion pledged annually, per OECD 2024 data. Brazil’s Amazon lost 11,088 km² in 2024, while Indonesia’s orangutan habitats shrank 10% since 2015. Initiatives like Costa Rica’s Payment for Ecosystem Services, covering 17% of its forests, show promise, but scaling such efforts requires political will. In India, population pressures and projects like highways through forests exacerbate losses. Kerala’s PBRs are a start, but without global cooperation, adequate funding, and prioritizing ecosystems over short-term gains, harmony with nature remains a fragile hope.