Ecologist Marx: Theoretical Trajectories of Degrowth

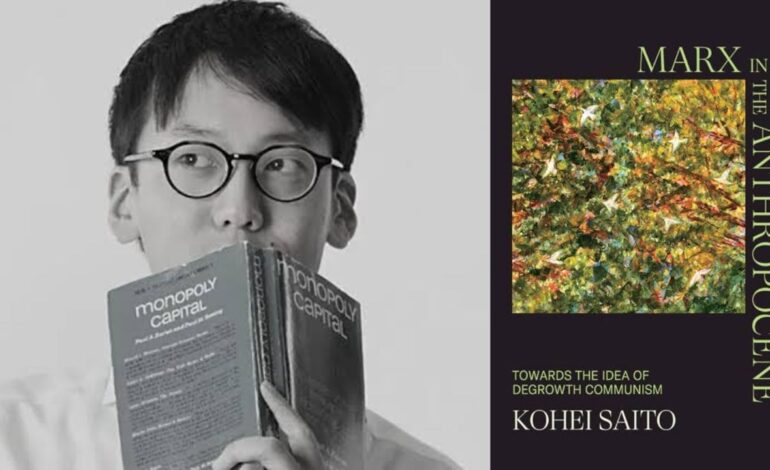

Reading Kohei Saito’s Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism (Part – 3)

It comes as no surprise, as Karl Popper (1967) points out, that Marx’s “historical materialism” has often come under criticism for its economic determinism. Two key features of this determinism are “productivism” and “Eurocentrism.” Productivism is rooted in an optimistic faith in capitalist modernization, wherein the technological and scientific innovations spurred by market competition are believed to eradicate poverty and reduce working hours. These advances, once limited to the ruling elite, are now thought to benefit the working class, thereby democratizing prosperity. This view places the development of productive forces as the engine of historical progress and sees accelerated capitalist development as the most efficient path to human emancipation—at least in the early writings of Marx.

Such a perspective not only champions a linear progression of history but also assumes that Western capitalist nations—with their superior productive capacities—occupy a higher rung in the historical ladder. Consequently, it concludes that non-capitalist nations must follow the European path of capitalist industrialization to establish socialism. However, Marx’s studies and notes from the 1870s signal a significant departure from these conclusions.

The breadth of Marx’s research, as recorded in his notebooks, is staggering. These writings span across disciplines such as geography, chemistry, mineralogy, and botany. They reflect a deepening ecological critique of capitalism, touching on issues like rampant deforestation, cruelty toward livestock, the reckless exploitation of fossil fuels, and the extinction of species. These explorations indicate Marx’s growing awareness that the celebration of productive forces under capitalism could no longer be sustained.

The notebooks reveal that Marx was moving away from the optimistic conclusions he once held. He came to recognize that the sustainable development of productive forces was impossible under capitalism. This system, driven by the hunger for short-term profits, ruthlessly exploits both humans and nature, leading to widespread ecological destruction. Capital accumulation, unchecked and insatiable, gives rise to increasingly complex and severe environmental crises. Marx thus realized that only an alternative economic system could mend the ruptured metabolism between humanity and nature. This insight forms the foundation of what would later be recognized as eco-socialism.

This transition toward eco-socialism represents a major revision of Marx’s earlier views. But as Kohei Saito notes, this shift marked only the beginning of deeper theoretical transformations. Marx’s decisive break from productivism disrupted the very foundations of his worldview—historical materialism. At this stage, Marx seemed to acknowledge that high levels of productive capacity alone did not guarantee historical advancement, especially when comparing Western capitalist nations to pre-capitalist, non-Western societies. It remains unclear whether Marx saw the development of destructive technologies as synonymous with human progress. Indeed, he referred to capital’s exploitation of nature as “robbery.” When Marx abandoned his faith in productivism—a core element of his earlier historical vision—he was compelled to reconsider the Eurocentric bias in his thought. If Marx rejected both productivism and Eurocentrism, then, as Saito suggests, he might have fully distanced himself from the conventional understanding of “historical materialism.” This shift likely came with personal struggle, yet Marx did not abandon his project; his continuing investigations into global history and non-Western societies attest to this commitment.

By the late 1860s, Marx had become more critical of Western imperialism and the limitations of globalized capital. Instead of glorifying colonialism’s so-called “dual mission,” he began to problematize the uneven subjugation of peripheral regions within the global capitalist order. His changing tone during this period aligns with his evolving critique of capitalist “productive forces.” As a result, Marx’s outlook on non-Western societies began to resonate with perspectives now found in modern ecological thought. His growing solidarity with the Irish struggle against British colonialism reflected this transformation.

Saito argues that Marx’s theoretical shifts regarding Prometheanism and anthropocentrism did not occur simultaneously. Rather, they should be seen as outcomes of his break from historical materialism. In a letter from March 1868, Marx found a “socialist tendency” in the works of Carl Fraas, and similarly in the writings of Georg Ludwig von Maurer. At that time, Marx was reading both Fraas’s ecological investigations and Maurer’s historical studies of ancient Teutonic communes. These two areas—natural science and pre-capitalist/non-Western societies—would profoundly influence the later Marx.

Saito observes that through these readings, Marx began to reflect critically on the flaws of his earlier unified framework and started paying closer attention to the specificities and diversities of non-Western societies—especially concerning Asiatic modes of production and their historical transformations. Kolja Lindner (2010), cited by Saito, notes that in the famed Ethnological Notebooks, Marx actively dismantled the Eurocentric notion of linear development.

By the early 1880s, Marx underwent a profound transformation in his view of history. He began to seriously entertain the possibility that Russia’s rural communes, rooted in communal property, might leap into socialism without traversing the destructive path of capitalist modernization. This marked a major shift in his historical imagination. Marx’s attention turned to the active resistance in non-Western societies against capitalist expansion, which led him to view the Russian revolution as a genuine possibility.

Saito contends that this insight should not be confined to Russia alone. It could also apply to other agrarian societies Marx studied in depth during that period—across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Theodor Shanin (1983), in his close reading of late Marx, interprets these writings as indicating that Marx saw Asian societies as resilient agrarian communities that had withstood war and colonization.

Unlike in the 1850s, when Marx had praised colonialism’s “civilizing mission,” later drafts of his correspondence—such as the third draft of the letter to Vera Zasulich—strongly condemned the destruction wrought by British colonialism in India. He decried the devastation of indigenous agriculture and the exacerbation of famine conditions.

Marx envisioned that non-capitalist societies were capable of resisting capitalism on different fronts and that they held the agency to establish socialism as a new phase in human history. Considering this later transformation in Marx’s thought, Kohei Saito argues that it is unjustifiable to dismiss Marx as an ‘Orientalist’ (in Edward Said’s sense).

This marks a crucial turning point. A truly fresh interpretation of the later Marx is possible only when the problems of Eurocentric, productivist approaches are critically examined in the context of contemporary conditions. The task of transcending the limits of capitalism and establishing communism remained a central theoretical and practical commitment for Marx throughout his life. It is true that in his early letters to Zasulich, he did not engage with this issue. That is because it was only in 1881, based on his in-depth studies of rural communes, that Marx began to shape his perspective on non-class societies.

Kohei Saito, through his work, explains how Karl Marx—who lived and died in the 19th century—continues to make theoretical contributions to the ecological advancements of the 21st century. He brings to light the long-overlooked environmental thinker within Marx.

Kohei Saito is an associate professor at the University of Tokyo and a prominent scholar in Marxian studies. His 2020 book Capital in the Anthropocene sold over half a million copies.

Concluded.

Click to read Part 1 and Part 2 of the series. Translated from Malayalam by Sania KJ.