On Taxonomic Imperialism

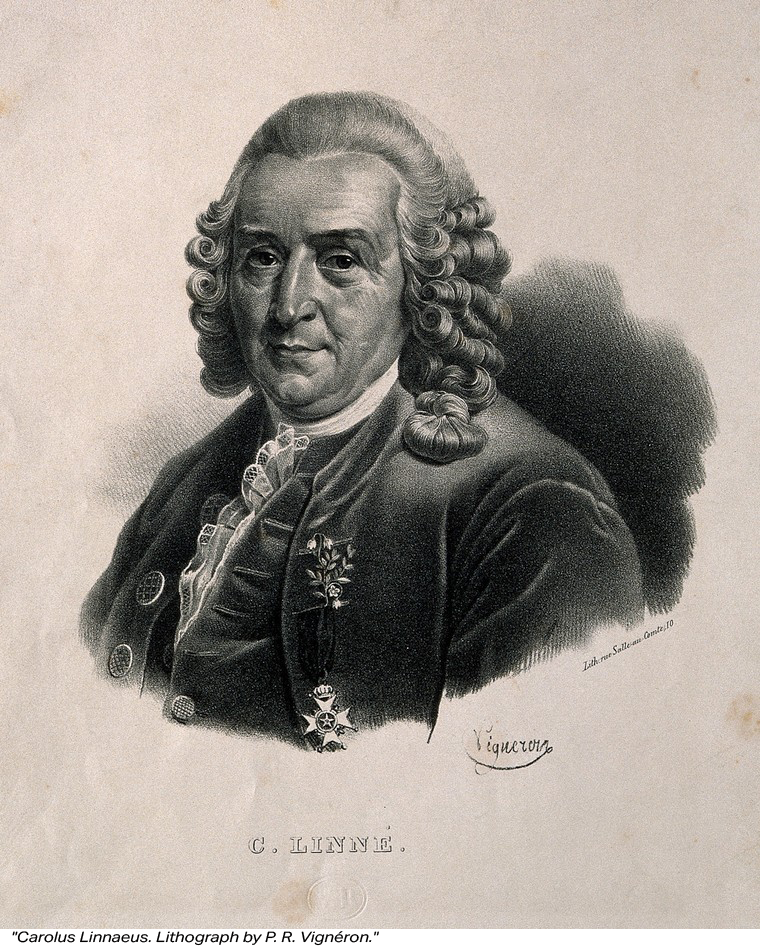

In the hushed halls of natural history museums and the precise pages of taxonomic journals, a quiet revolution is brewing against one of science’s most entrenched systems—the way we name life itself. When Linnaeus formalized binomial nomenclature in 1758, he created more than a classification system—he established intellectual borders as rigid as those being carved across continents by European powers. Just as the Berlin Conference of 1884 partitioned Africa with geometric precision, the Linnaean system dissected global biodiversity into taxonomic territories governed from Europe. Today, this parallel empire still governs how we speak of life itself, its borders patrolled by commissions and museums, its laws written in academic journals few can access. The specimens lining museum cabinets—their Latin names etched in neat cursive—are not merely scientific artifacts but trophies of a centuries-old campaign to remake global biodiversity in Europe’s image, erasing indigenous relationships with the living world through a process of ecological alienation as profound as physical displacement.

The machinery of this empire operates through institutions like the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), where decisions made in London determine whether a species is classified as “new” or merely “varietal,” often rendering culturally significant beings scientifically invisible. The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), revered as the “polite animal” in Vietnamese highland communities, became reduced to a zoological curiosity when Western scientists described it in 1993—its behavioural traits that inspired local conservation taboos dismissed as folklore. Similarly, the Sunda flying lemur (Galeopterus variegatus) appears in taxonomic literature as “bizarre” and “primitive,” adjectives that reveal more about Western projections than biological reality. This exoticizing gaze creates what might be called “taxonomic orientalism”—where tropical species exist primarily as fantastical curiosities rather than ecological agents.

The psychological impact on indigenous communities’ mirrors what psychiatric anthropologists call “cultural bereavement.” When the Yurok people of California must refer to the condor (Gymnogyps californianus) by its Latin name rather than “prey-go-neesh”—a term encoding its role as spiritual messenger—they experience what Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith describes as “epistemic dislocation.” A 2021 study in Environmental Psychology documented how forced use of scientific nomenclature decreased traditional ecological knowledge retention by 42% among younger generations in studied indigenous groups. The trauma is particularly acute for species like the orangutan (Pongo spp.), whose name derives from the Malay “orang hutan” (person of the forest)—a recognition of personhood systematically erased in Western zoological texts that reduced them to “specimens.”

The economic architecture sustaining this system reveals its true function. The average cost to process a new species description through Western institutions exceeds $5,000—a sum greater than the annual research budget of many tropical universities. This financial barrier maintains what Brazilian botanist Dr. Rafaela Forzza calls “scientific dependency,” where biodiversity-rich nations must outsource the basic documentation of their own flora and fauna. The consequences are measurable: while Madagascar contains 5% of Earth’s plant diversity, 83% of type specimens from the island reside in European herbaria.

Yet cracks in the colonial edifice are widening. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History now accepts traditional knowledge as valid type material—recognizing a Māori carving of the extinct huia bird as a nomenclatural standard alongside physical specimens. In Kenya, the National Museums have incorporated 412 Kikuyu plant names into official databases after a decade-long validation process showing their superior ecological precision. Most radically, India’s Botanical Survey has begun issuing “parallel type certificates” that grant equal standing to Sanskrit descriptions from ancient texts like the Charaka Samhita (circa 300 BCE) and modern Latin diagnoses.

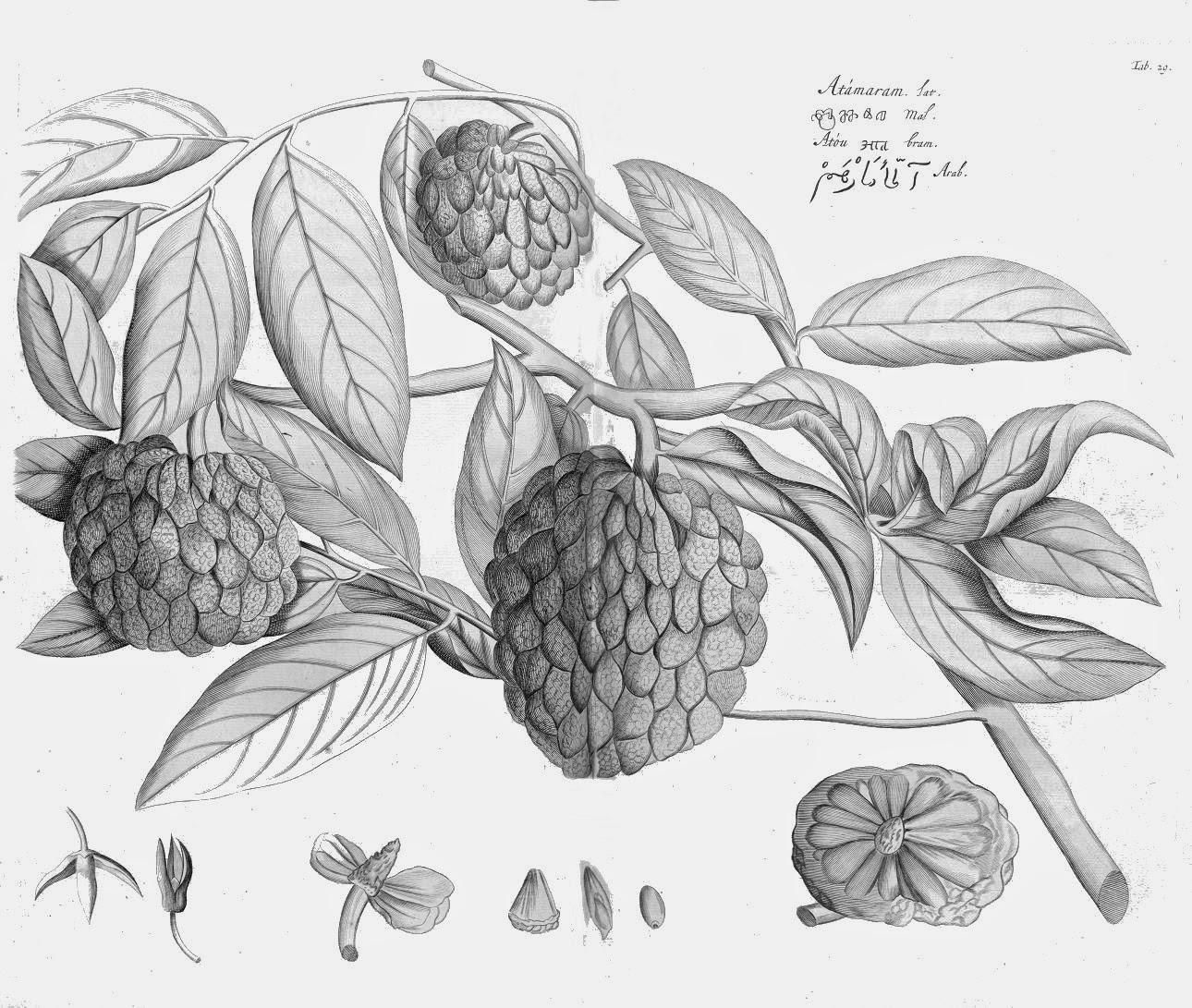

These developments expose the central fiction of taxonomic objectivity—that naming can ever be divorced from cultural perspective. A single flowering plant in the Amazon is simultaneously Brugmansia suaveolens to a taxonomist, “toé” to a Shipibo healer (denoting its 7 distinct ceremonial preparations), and “wanachama” to neighbouring tribes (marking its role in seasonal bird migrations). The emerging paradigm suggests true scientific rigor requires holding multiple truths simultaneously—what anthropologist Dr. Kim Tallbear calls “ontological pluralism.”

As European institutions begin returning type specimens—the Naturalis Biodiversity Center recently repatriated 37,000 Indonesian specimens—we glimpse a post-colonial future for taxonomy. The Field Museum’s “Collections for the People” initiative trains traditional healers in genomic analysis, while the Kew Gardens’ “Open Herbarium” project shares 3D scans of type specimens with source communities. These aren’t acts of charity but of epistemic justice—recognizing that the 30% “discovery gap” in tropical taxonomy (species known locally but undescribed scientifically) represents not a lack of knowledge but a surplus

The revolution will be taxonomic—not through replacing Latin names but dismantling their monopoly. A medicinal plant in Kerala is simultaneously Ocimum tenuiflorum to a taxonomist, tulasi to an Ayurvedic practitioner, and the physical embodiment of Lakshmi to devotees—all equally valid ways of knowing. The path forward demands concrete action: repatriating type specimens to their ecological contexts, dismantling predatory publishing fees that gatekeep scientific participation, and granting traditional classification systems equal epistemic standing in research.

Should learn from young adults and I am learning not to condescendingly praise them. Reading the world through the new lenses they provide. 🌹🌹

“If you do not know the name of things, the knowledge about them is lost too”- Carl Linnaeus… But naming should not be confined to scientific and common names alone. It must also include the local names used by communities who coexist with these species. Local names are evolved through years of close interaction, observation and coexistence reflecting rich traditional knowledge, something that is often overlooked by modern science.

Very well written article Akhil

Thank you for the thoughtful comment. I agree—local names reflect rich, place-based knowledge that science must recognize as essential, not secondary.