How Manipur has Changed since the 1980s

Along with the edited transcription of the first episode of “People and Places with Bala”

Venkitesh Ramakrishnan (Managing Editor of The AIDEM): Hello and Welcome to the new series, ‘People and Places’. People and places matter in everybody’s lives. All of us remember people, all of us remember places, there are special people, special places, which kind of guide and control our Lives. It may have happened many decades ago but one incident or a personality will continue to influence us. And to start this program I have a very special person, Balagopal Chandrasekhar.

A man who has literally worn very many hats; he was a bureaucrat, he was an entrepreneur, a failed entrepreneur to start with and then successful entrepreneur.. a man who has kind of handheld many startups. He was also till recently the chairman of the Federal Bank. In his first book, where he recounts his experience as a bureaucrat, the book titled, ‘On a Clear Day, You Can See India’, he says, “Faces and sights and landscapes and smells and sounds and tastes from a long time ago floated up, as each memory was recalled.“ So, people and places have always been part of your life. Welcome to this program. There is a special context in which we are talking to you today. Because your career as a bureaucrat began in Manipur, which of course is now a major focus area. I can even say it is in the eye of the storm. So, you’ve worked there in the 1980s and of course you’ve been in touch with that region for a very long time. Can you tell us something about Manipur then and Manipur now?

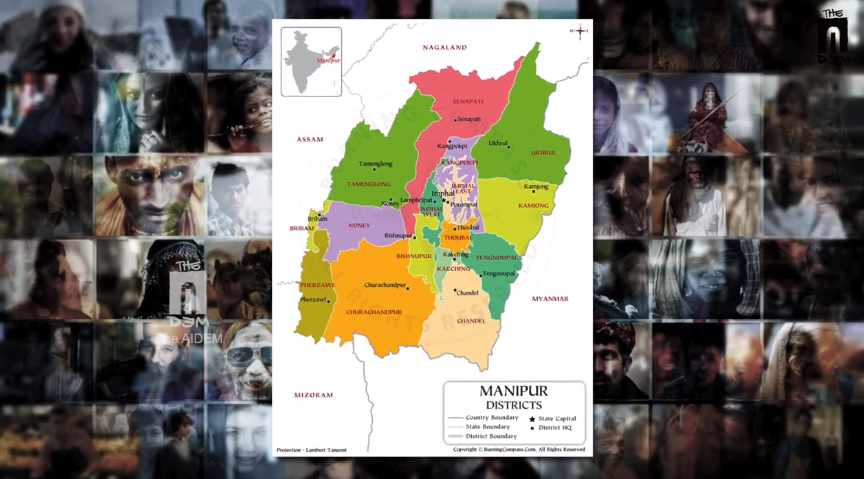

Balagopal Chandrashekar (Author, Entrepreneur & Former Chairperson of Federal Bank): Thank you Venkitesh for that nice introduction. Manipur when I worked there, which was in the late 70s and the early 80s and Manipur today, I find them very different places. The state of course has grown a bit in population from about a little more than 2 million population those days; now it is around 3 million. Of course administratively it has grown because in those days we had only four districts and now I think there are 16 districts. So this administrative inflation is happening like it is happening in many parts of the country.

Q: Yes, it is happening all over the country. In fact you mentioned that in the book itself.

A: That’s right. But one major difference is while Insurgency and the political disaffection was fairly strong even then, the problem was seen to be a political problem and was being tackled at the political level those days, with the armed forces not in the scene at all. And even in troubled areas where there was a need to impose curfew, those areas were patrolled by BSF and CRPF, which are the paramilitary forces. There was one brigade, one army brigade, in a place called Leimakhong outside Imphal but they were always in the barracks. They were never seen outside. The only other paramilitary formation which was evident by the various camps which they had were the Assam Rifles. The Assam Rifles were a paramilitary formation with the officers drawn from the army. They wore uniforms which looked like the army but they were, strictly speaking, not army. So, why I am saying this at length is that the clear approach was seen to be a political approach and there were channels through which talks were going on regularly with the Naga insurgents and the Manipuri Insurgency groups also. Then, it was in the mid 80s to late 80s by which time I had already left the service, having decided to become an entrepreneur, it was around that time that a certain decision seems to have been taken in Delhi, especially North Block where the Home Ministry is located, to beef up the military presence in Manipur. What was previously a token army presence in a border state in the form of an army brigade at Leimakhong was replaced by a full mountain division which moved in. And in fact I remember one of my service friends humorously writing to me saying the vehicle population of Manipur had doubled after the mountain division moved in because a mountain division has so many vehicles or trucks and others from armoured personnel carriers and artillery units and things like that.

Q: You are talking about the mid-1980s?

A: Yeah..mid-1980s to the late 1980s. Even at that time I remember feeling that this was excessive military force for what was, you know, in terms of sheer numbers, always seen to be a few hundred members of the various Insurgency groups, never totaling more than a thousand. So obviously this was based on some very alarming perception of the scene in Manipur.

Q: But now what was the reason for that kind of depiction, an understanding like that? Because as what you have just said must have been the view of many bureaucrats, many police personnel and many security specialists ; that there were not more than a thousand people there (in the various insurgency groups).

A: That’s a very good question because even when I was working there as a young Sub Divisional Officer in Ukhrul and later in Imphal, we used to feel that there was overreaction.. When we used to read the mainland newspapers, we used to wonder.. on what basis are they writing this kind of alarming information? Because we who were on the spot didn’t feel the situation warranted that kind of alarmist picture. So I think a combination of some half truths which were going down from anecdotal sources plus huge ignorance on the part of the senior people sitting in the Home Ministry, many of whom had probably never been to the Northeast and to Manipur themselves, their perceptions were formed on the basis of this incorrect information and half truths..

Even in those days we used to say, many of the correspondents never came to Imphal. They used to sit in Guwahati or Calcutta and file their stories. And today I believe it’s particularly true that very few people are going to Imphal to go into the troubled areas and to find out..

Q: I am also told that going to the hills where the Kukis are in majority, that is physically impossible even now. Only a handful of journalists must have gone. In fact your book was written way back but then you have mentioned this very clearly. You said that “mainstream national media and consequently mainstream public opinion appears to still be mired in the cliches and images of the past.“ Do you think that this still continues?

A: There is this ignorance about the Northeast which is displayed sometimes almost semi-comically by exaggerating incidents which happened there but more sadly by the indifference to what is really happening there. For example, today if you see in the media, there is a very dangerous tendency to project what is happening in Manipur as a religious kind of conflict; one between Hindus and Christians. In my opinion that is far off the mark. That is completely missing the point.

I believe that it is more of an ethnic problem between the valley and the hills. The valley was always represented by the Meiteis, who were the settled civilization there; whereas the hill people were either Nagas or Kukis, Mizos etc. And that was more of an unsettled shifting population. And there was constant movement of populations across international borders too because this whole area spilt over into the northern parts of Burma, Myanmar. The real root of the problem in my opinion, and actually this is not based on my study because I don’t have that much scholarly knowledge of the Northeast, but I rely on the information of an outstanding journalist in Manipur, who lives in Imphal. His name is Pradip Phanjoubam. He has written, what is in my opinion, some of the magisterial works on the Northeast, and many of them actually point to the seeds of the problem, where he talks about the Inner Line regulation, which was imposed by the British towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

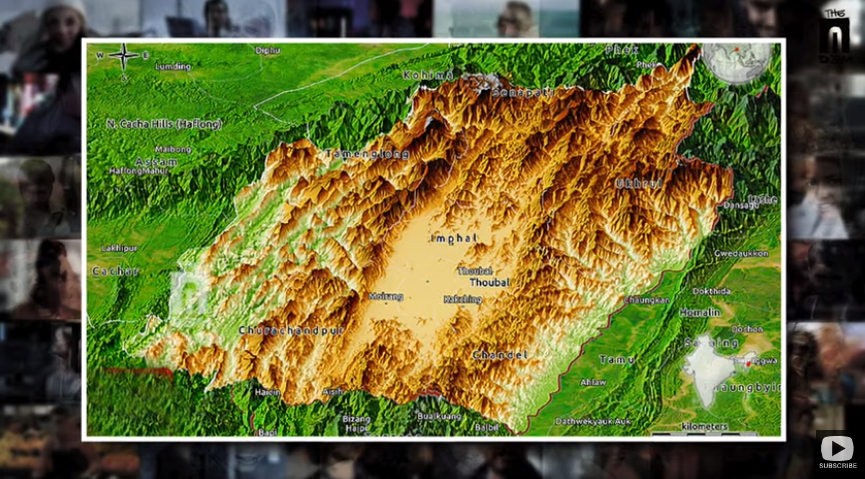

In my opinion, that is what really has laid the foundation for this apparently unsolvable ethnic dispute between the hills and the valley. So, just to explain what that Inner Line is… when the British moved into Manipur, they moved into Manipur on the side of the Manipur king, to expel the Arakan Kings. The Manipur king and the Arakan Kings used to constantly be at war and the Manipuri Kings used to also have battles with the Ahom Kings. It was a constant state of conflict. So, the British intervened on the side of the Manipuri king and they defeated the Arakan king then and established the British suzerainty over this area.

But they never really occupied it like the rest of colonial India. Instead they placed a Resident there and they moved out. They moved back their troops but the message which was sent to the Arakan kings was that this is a British protectorate under British protection. The British had adopted a policy in Assam, which they sought to extend to all settled areas. What the British did was to draw a line along the foothills where the valley meets the mountains. I mean where the flatland meets the mountains. And that was called the Inner Line. And towards the hillside or the mountain side of the Inner Line, the land revenue regulations did not apply. And the hill people were warned not to step on this side.

As Pradeep Phanjoubam writes, there is an intimate relationship, not just in Manipur, in all the geographies across the world, that the hills can never be separated from the valleys. The valley is meaningless without the hills and the hills are meaningless without the Valleys. So there was a constant movement between these two. But this British Inner Line system, confined the hill people to the hills but more cruelly confined the valley people to the valley.

Why I say, more cruelly, is because one of the facts about Manipur is that 90% of the surface area of Manipur is mountainous. And only 10% is in the valley. Whereas 60% of the population of Manipur is Metiei who live predominantly in the valley and only 40% are the various tribes. So, 60% of the population got confined and restricted by law to 10% of the land and there, I believe, started an enormous sense of grievance.

Q: There is also the point that in terms of political power equations, because of the advantage of population, especially in recent years, the Meiteis have had a bigger share of political power. Whereas even though the hill people had more land and other resources, they were not having the same kind of share in power. And also coupled with the fact that Manipur must be the only state where an aggressive or forced Hindu proselytisation took place among the indigenous communities. So, when you say that this is not exactly a Hindu-Christian problem, there are also dimensions which are kind of contiguous with it. Don’t you think so?

A: Yes.. But again I think that is purely because of the coincidental problem between the valley and the hills. So the valley people are Meitheis and the hill people are the Kukis and Nagas and therefore now it so happens that all the overwhelming percentage of the valley people a few years ago were Hindus and an overwhelming percentage of the population of the hill people were Christians. So, that is purely a coincidental thing but religion was never the trigger. There were hardly any slogans or anything. It was not the primary parametre.

The other point is, you’re right about the share in power. Because of democratic processes that we have, dictated by first past the post, there is an imbalance in power share. The community or the faction which has the numbers will then naturally rule. The same thing is happening in reverse in Nagaland and Mizoram and Assam and various other places where whichever ethnic group is in the majority, its diktats will run across the state.

In Manipur therefore one shouldn’t be surprised that once democracy came there, and the elections started to be held, the numerical superiority of the Meiteis reflected in political power. But notwithstanding that, there was a lot of interchange and exchange of people and the movement between the hill and the valley till the Inner Line regulation came to be. The Inner Line regulation also meant that it had a cruel one-sidedness to it. And this was that the Meiteis could not own land in the hills. But the hill people could come and own land and property in the valley. That was a second source of grievance and bitterness among the Meiteis, which was growing. The third source was that for various reasons, the Meiteis were rejected the scheduled tribes status but the hill people got scheduled tribe status, which meant they got preferential appointment to the central services. So, initially being from the valley was a matter of pride but later on it turned out to be a double edged, counterproductive.

Q: I remember reading in your book that as part of the proselytization, the Meitei had also assimilated and imbibed the ‘Chaturvarna’ system, including at the level of caste hierarchy and all that. That must have also been one of the reasons for them to be denied the…

A: That’s right. It was a sense of superiority but not not only because of the Hindu ‘Chaturvarna’ system but also because of the fact that they were the rulers. In that whole mountainous belt, the only place which had a standing army was the valley. To have a standing army you need settled agriculture, and the only place which had settled agriculture was the Manipur valley and the valley was very fertile. And so it could support a standing army. That’s why on equal terms they could take on the much bigger and much more powerful Arakan Kings and the Ahom kings, who generally stayed away from trying to subjugate this troublesome kingdom area called Manipur.

But to come back to the other things, all this added to the Meitei grievances. During this time, the Naga and the hill people of Manipur were having their own problems with the Indian Union in the form of insurgency movements, and independence struggles, and also autonomy issues. They were fighting a separate kind of battle but this grievance which was mounting in the Meiteis, I feel, had passed on unnoticed and unattended to. Nobody gave it any weightage. It just needed something to let the genie out of the bottle. Unfortunately, a very poorly timed, and ill-advised judgement by a High Court Judge of Manipur chosing to entertain a petition and pass such an extraordinary order which has now been set aside by the Supreme Court… but then the damage is already done. The opposition to this judgment is what seems to have triggered ferocious response from the Manipuris. Because the Manipuris felt whatever the judge had ordered will cause the extension of all Schedule Tribes benefits to be extended to Meiteis too…

Q: There was also a counter reaction to that.

A: Protest turned against the Meiteis.

Q: And also perhaps there was also some kind of political prodding from some sections of the ruling classes…

A: Oh yes. I would not put it beyond the main political formations in India to try and stir the pot and create some more problems. When you’re dealing with things like this, as Pradeep Phanjoubam said, when you’re dealing with the deep-seated grievance and injury which cannot be just papered over, we have a real situation, we have a real problem.

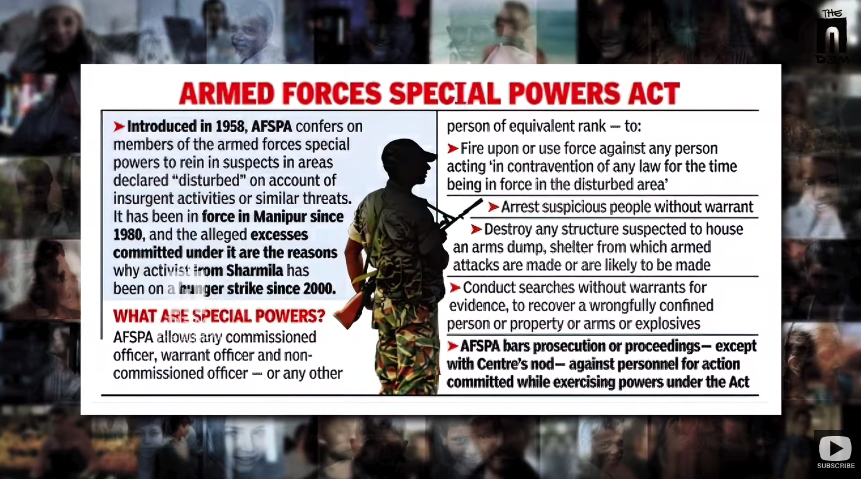

Q: There is a strain of opinion especially among the armed forces and senior officers who have served in the northeast and in Manipur, who say that perhaps the biggest mistake that was done by the powers that be, was the withdrawal of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. What is your take on that?

A: I have written about that in my book. The decision to send the army is a political decision and the problem is once the army goes in, we forget that the army is not a police force. The army, the soldiers and their officers…and their sole mission is to defend the country against external aggression; and internal threats which are so serious that the police cannot handle it and it threatens the Integrity of the country. Then in an extreme situation, you send the army.

Now I am not an authority on the laws that come into play on such occasions. I have forgotten much of what we were trained in the Academy about this extraordinary situation called martial law but what I remember is that the army was, strictly speaking, to be used only in the extraordinary situation where martial law is declared. In such a situation, the rules are apparently that the situation has gone out of control of the civilian administration. Therefore martial law is declared and the situation is handed over to the army to restore calm and quiet, restore order, and hand it back to the civilian authority.

I think, both the army and the officers commanding those units, as well as the civilian administrators and the politicians who took the decision to send the army in, were unclear about the multiple dimensions of the situation here. So I think this ambiguity is what has created the problem. The Armed Forces Special Powers Act was to protect the army officers, I mean army personnel operating under such situations. I think that is not a good solution at all. And I think the old regulations were good where you have had a situation either managed under the civilian administration or when the civilian administration is deemed to have collapsed, the situation is handed over to the army and martial law declared, so that there is no ambiguity. So, my answer to your question is that I think the Armed Forces Special Powers Act is unnecessary. In such ambiguous situations, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act can lead to all kinds of troublesome situations, legal and political.

Q: So the long and short of it is that the situation now is actually a situation where it is of extreme concern. But you also said when you were there there was only one Brigade and you also made it very clear that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act was not necessary for a state like Manipur. But now there is a situation. How do you think that this can be handled?

A: I still think it is a political problem and has to be handled politically and the most important thing which is necessary is that people must start talking. I see no evidence of any talking going on between the contending parties because all that we hear are some very bad reports of terrible incidents which happened some time back a few months ago. They are slowly coming out and so people who read the news do not realise this happened on 3rd of May or 4th of May. Of course, the perpetrators must be brought to book but the impression when you read the media is that this just happened. So, the way it is presented is also wrong. There is no clarity. People are under the impression that there is a continuing kind of insurrection.

Q: That is happening. We are getting reports of people getting killed on a day-to-day basis.

A: Since I really don’t know too much about that other than what I am reading in the media. One of the things which has apparently happened is that there has been a kind of ethnic cleansing which has happened in the valley and in the Kuki dominated areas of southeastern Manipur. All the Meiteis from the southeastern hill areas have either returned to the valley or are in camps protected by the army. Similarly the Kukis in the valley, which is the predominantly Meitei area, are in camps or have returned to their hometowns, which means that it is a very bad sign. Because it means that there is now no dialogue, or contact, no interaction. People are just sitting there bitter about the loss of their near and dear ones, loss of their property, loss of their jobs, and this will only fan and keep the bitterness very strong.

So, I think the first step which is needed is there must be very high level intervention, like from the Prime Minister, people like that must all be in Manipur and get people to sit across. When prestigious people like the PM and all go there, then everybody will come to the table. But, here if it is left to a Chief Minister who is seen as discredited, and if you expect him to solve the problem, he is not going to be able to solve the problem because the people on both sides of the divide see him as part of the problem.

So I think the thing is, number one, the conversations are not starting, number two, there are to be interlocutors pressed into service there, people who are really knowledgeable about the region and about the history of the region. I can take one name, for instance, of a former Home Secretary, G.K. Pillai. G.K. Pillai is one of those guys who is very knowledgeable about the northeast. He was highly respected because he was seen as fair and even-handed by the Nagas, by the Meiteis, by the Kukis, and also by the Assamese. Everybody accepted him. Now there are very few figures like him today. He is long retired and I know he is still very active in certain circles in Delhi.

Q: The title of your book is very interesting, which is, ‘On a Clear Day, You can See India’. You depict that in one of the chapters the book, where your first District Collector, whom you have named as RN, takes you out on a field trip and then he shows you the East, West, South, and North and he has got a wand in his hand, and he says that on a clear day, you can see India. What do you exactly mean by that?

A: This particular District Collector was a very wry, laconic, kind of individual. He had a wry, dry, sense of humour. I think what he was saying when he pointed towards the West and said, on a clear day, you can see India… what he was referring to was not only the physical distance. People don’t realise how far away Manipur is. I remember, when I was preparing my first TA Bill to go and join my office in Imphal, I discovered that by rail, the distance was three thousand four hundred and odd kilometres.

You are still in the same country and you have 3400 kilometres to travel from your hometown to reach this place. More than the physical distance was the fact that we have one timezone in India which is actually quite absurd. Because in Manipur, I remember, after four o’clock Indian Standard Time, there’s no Sun.. when we look at a watch it is four o’clock, but it is dark. For the first few weeks and months, it took us great difficulty to adjust because outside it was dusk. Sun had already set and it was still four o’clock. And it is only 4.30 in the morning when the sun is already risen because that far East it is.

Many people don’t realise that the line of longitude which passes through some parts of Arunachal Pradesh is the same line of longitude which passes through Thailand. So, there are parts of India which are so far east that they are as far east as Thailand is from India. So, there is a time factor and third is a mental distance that is the most crucial.

People referred to in my book, for example, my driver, used to conversationally ask me, “sir, in India, how are wedding ceremonies?” And I used to feel very lonely at that time when he said that. Because here I am a young guy, 26-27 years old, and I am on my first posting, and this guy is asking me, in India, how are things? He was not saying it to irritate me. It was just very natural, it came very naturally. They felt that we were aliens and there was a word in Manipuri for alien, and it is called ‘Mayang’ and ‘Mayang’ was not a complimentary term… it was a slightly derogatory term. We were all called ‘Mayangs’ and that same sentiment was returned by most people from India who will speak in such terms even in the presence of Manipuris…they will talk in a not very complimentary way about the local people. All this has created a mental distance and that is what I think my District Collector was meaning when he said, on a clear day, you can see India.

Q: Well, Balagopalji, I think we will continue this conversation in People and Places. The long and short of today’s discussion that we have had on Manipur is that he had experienced, or at least his District Collector had talked about the huge physical and mental distances that are there between the national capital of India and Manipur. And what recent events are showing us is that distance is yet to be properly overcome and that we have not been able to get through those distances, and to create a sense of amiability. But hopefully, things will change for the better with more and more knowledgeable people understanding, and with people in positions of power actually taking up the responsibility and taking up the dialogue forward. Thank you.