‘Orbital’: A Space Saga of Anthropocene; A New Narrative Form Reflecting Future Technology

British Author Samantha Harvey’s space odyssey, ‘Orbital’, winning this year’s (2024) Booker Prize, is a success of contemporaneity led by an acute awareness of global capital’s priorities, no less unique still, with its beautiful prose and thoughtful take on the fragility of the Anthropocene. To read the book is to suffocate oneself inside a transparent water bubble and still feel the wind on one’s face, like flying over green forests, emerald oceans, and across the blue sky.

Choosing Samantha Harvey’s book for this year’s Booker Prize, the Chair of judges observed, “Orbital is our book. Samantha Harvey has written a novel propelled by the beauty of sixteen sunrises and sixteen sunsets. Everyone and no one is the subject, as six astronauts in the International Space Station circle the Earth, observing the passages of weather across the fragility of borders and time zones. With her language of lyricism and acuity Harvey makes our world strange and new for us.”

‘Orbital’ brings into focus what we think is peripheral to our existence but still defines us in many unknown ways. Primarily our thoughts. Our thoughts represent another world, but in our daily existence, limited by time and space, we mostly banish them to an outlier life. We ignore them, mock and scoff at them.

In space, the astronauts have the right distance from Earth to slip into the world of thoughts, to drift away from a profound material existence that all have on Earth. Life and its multitudinous details do not bother them there, and the thoughts take over. They have quite similar thoughts, but they rarely share them. They still try to live outside of those thoughts, but it is a pretence, and they know it. Samantha Harvey’s book is a mosaic of thoughts painted on a cosmic wall.

David Storey, another Booker winner, had observed (before winning the prize for himself), “Prizes tend to be rewarded to the reliable rather than the liabilities, and the liabilities are the people who matter in the end.” The truth lies somewhere in the middle of this statement.

‘Orbital’ signifies that truth in many ways. It caters to our contemporary reality of a new age of space exploration. It hopes to engage with this generation, of this new age. Will it stand the test of time? Only time can tell.

The book is reliable, to begin with, given the peak interest in dystopia- climate or otherwise- and ‘outside Earth’. With the US Senate hearing on UFOs and UAPs, the billionaire dreams of space travel and colonisation, and a career avenue opening from all the above, the book ticks many boxes. It is not a crime to be popular, and this, indeed, is a magnificent book.

The book tells the story of six astronauts from different nationalities living on an International Space Station. They rotate the Earth each day 16 times, and on each rotation, they stare down through their windows on the blue planet with intense longing, a bizarre detachment caused by the distance and their zero gravity, and an acute awareness of how fragile life is. Some strange dreaminess that the space induces in them.

News of the death of dear ones, the duty to monitor a precipitating super typhoon over the Pacific moving towards human habitation in southern Asia, occasional glimpses into the mundane life on Earth through letters from family and routine chats with the ground crew, an odd growing desire to never leave, an exercise regime to reverse the effects of microgravity, a sleep that imitates hanging bats, a to-do list for after-return Earth life – a list that borders on nonsense as they include a blue pen with red lid, children in a bow tie and the like- and the evolution of a single organismic entity merging the spaceship and its inhabitants, all amalgamated together like organs inside a body, a bizarre organism closely watched every moment by the ground people.

The narrative circles life, Earth, its people, climate, existential questions, and the infinity of space like ripples in calm water. It does not progress as it does in many stories. It is an ocean pool in an emptiness. A spectacular sense of stillness gets hold of the reader, the stillness at the core of the whirlpool. Everything goes round and round about it in super slow motion.

The astronaut’s view of life and Earth cannot but be cosmic and defying borders. However, the astronauts are caught in a constant orbit that circles Earth. The thread of the story is knit in knots of Earthly concerns- climate change, borders, geopolitics, and futility of explanations. Too much philosophy, one might occasionally think, when past the middle of the book.

The story continues to revolve around Earth and the space station, two overlapping loops inside a gorgeous nebula of slow-burning prose.

This metaphor of rotation is incredibly meaningful if you think of the future of space explorations. The next milestone in space for humanity is Jeff Bezos’ private space station, the ‘Orbital Reef’, to commence construction in 2025. Simultaneously, NASA and the front runners of space also eye Mars as their next destination.

Both these explorations have one common hurdle to overcome- microgravity. To make a space station functional and running for years and to take a space crew to Mars, the primary prerequisite is the ability to create artificial gravity. The key to creating artificial gravity on a spaceship, space station, or planet like Mars is rotation. I will come to rotation in a moment, but first, let me explain artificial gravity.

What is Earth-like Artificial Gravity?

All visuals from spaceships show astronauts floating in a vacuum. But many space movies have people walking around normally on spaceships and cities built on other planets. How great is the distance from fact to fiction? When will humanity have the technology to create Earth-like artificial gravity in spaceships and new planetary dwellings?

The narrative of Samantha Harvey circles also the metaphor of gravity or rather the lack of it. Even the thoughts of her protagonists float like their bodies, creating a narrative form that resembles zero gravity, a form not experimented with before.

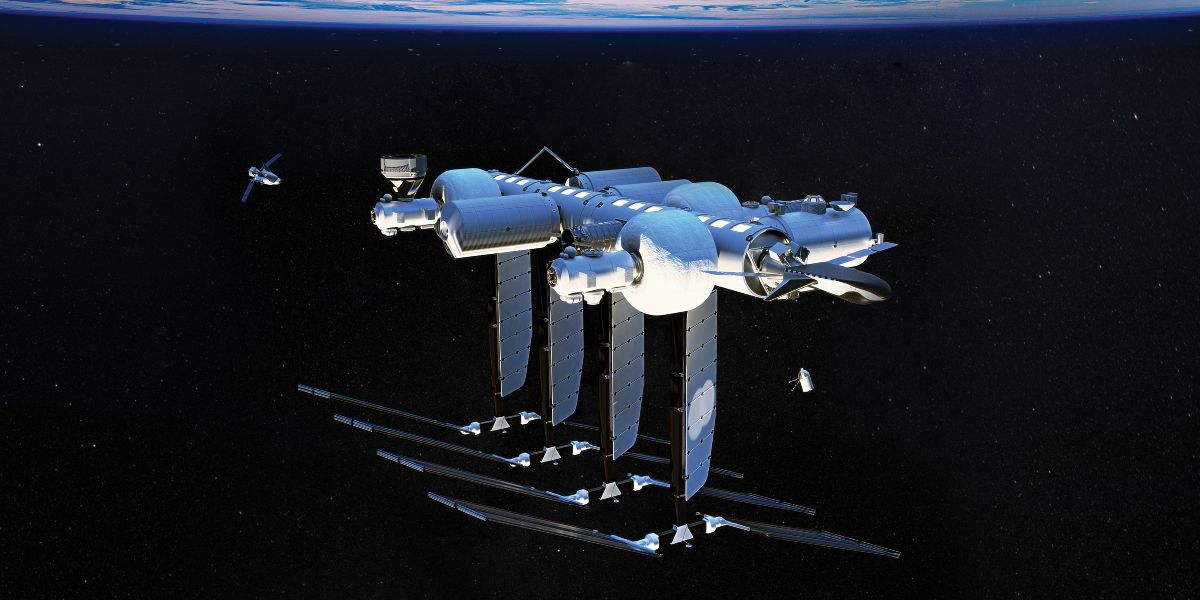

The lack of gravity, which is often referred to as microgravity, creates many health issues for astronauts in real life. Their limbs weaken, muscle mass deteriorates, and bone density decreases. They have to undertake rigorous exercise daily to maintain their physical well-being.

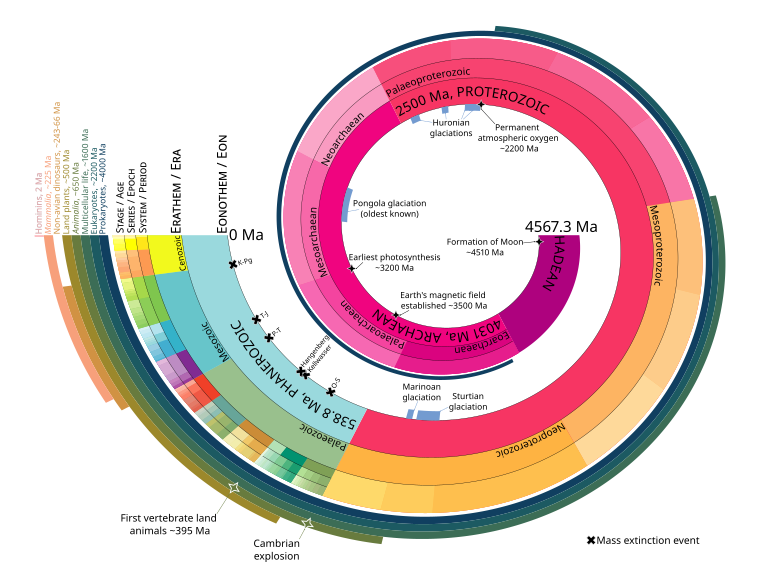

Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity says that gravity is equal to acceleration, and if you keep accelerating at a speed of 9.81 metres per second, which is the acceleration equal to the pull of gravity on Earth, you can stay grounded in a spacecraft. The basic concept behind this is that gravity and acceleration are identical. However, a spacecraft cannot always stick to a specific acceleration in space, which is the reason why we do not have the technology to create gravity in space.

Artificial Gravity: Potential Technologies

The O’Neill cylinder is a technology that has shown some potential to help create artificial gravity in space. In simple terms, it is a pair of gigantic cylinders rotating in opposite directions. Years of further research are needed to develop this concept into practical reality. Ideally, the cylinders have to be about 32 kilometres long with six 6-kilometre diameter. Once developed into a space machine, people will be living in this cylinder, which is weird and cute. Remember, this is why all futuristic spaceships that we see in movies are spinning constantly.

Spinning is the key to all models suggested to create artificial gravity. We must remember that Earth is spinning constantly, but the size prevents us from feeling the spin. Any spaceship or space station using the spinning technology will have to be a behemoth.

The father of the Russian space program, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, was the first to talk about the need for rotating space vehicles to counter the effects of microgravity on space travellers. From then, centrifugal force began to be seen as an alternative to gravity. For a human trip to Mars, we might need artificial gravity because the trip is going to be long. To undertake it without harming one’s health will be a challenge for any astronaut.

Dr Bill Palosky is a space physiology scientist and author who studied the effects of lack of gravity (microgravity) on the human body. He observes that an astronaut can mitigate most of the adverse health impacts of microgravity through physical exercise. He told a NASA podcast that this was why research in artificial gravity was not a priority till the 1990s.

Around 1999, a new health issue in astronauts surfaced in space research circles. Space Flight Associated Neuro Ocular Syndrome (SANS) was the new health problem detected in many of them. Changes happen to the brain and eyes of astronauts while staying in space. NASA has revealed that 70% of the astronauts in space suffer from swelling in the back of the eye.

The cause of SANS is simple- in microgravity, the body fluids, the blood and cerebrospinal fluid move towards the head as the astronauts float rather than stand and walk upright. The ventricular volume of the brain enlarges as a result. The health effects manifest as blurry vision. Under observation, these effects were found to be temporary. As the astronaut returned to Earth, the effect was reversed. Yet, it is an ongoing study without conclusive results.

Scientists continue to collaborate internationally to build systems that can create artificial gravity. As Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is planning the first private space station, ‘Orbital Reef’, by this decade’s end, this research has picked up pace.

Samantha Harvey creates the gravity to anchor her narrative in a new space. She crafts a poetic prognostication of an upcoming technological leap.

It is a detailed article with the touch exquisite poetic i enjoyed much congratulations to Samantha Harvey and Deepa who has created a sense of interest and curiosity to read the book