Varanasi’s Lost Decade – Part 1

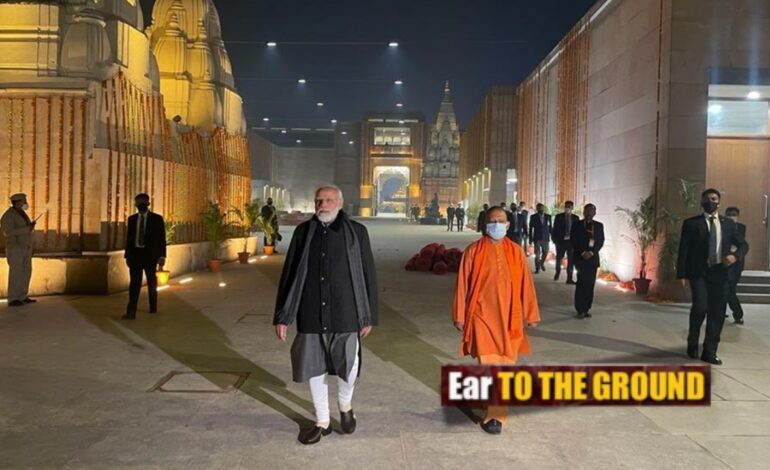

The AIDEM’s series “Ear to the Ground” comes back with a focused probe into the development story of Varanasi, the Lok Sabha constituency represented by Prime Minister Narendra Modi for more than ten years. This is the first article in the two part series.

On 26 January 2025, as India reaches the 75th anniversary of the country’s Republic, the temple town of Varanasi is marking a different kind of landmark. January 2025 marks ten and a half years since the time Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India, became a Member of the lower house of the Indian Parliament from the Lok Sabha constituency here. By the time Modi came to contest from this constituency in 2014, decades had passed since a high profile leader represented Varanasi in the Lok Sabha. Naturally, the popular expectations were huge and they were not just about routine development but substantial and all round transformation.

Varanasi, a prominent city for Hindus, is considered the oldest living city in the world. It’s commonly believed that its continuous existence goes back to 2500 years or more. For centuries, the city was a major center of trade and learning. It has been an important religious center, not only for Hindus, but also for Buddhism, Jainism, and Bhakti sects. Gautam Buddha gave his first sermon here after enlightenment. Four Jain Thirthankars were born here. Saints like Kabir and Ravidas were born here and spent their lives here. Tulsidas wrote Ramcharitmanas in the city. In 1916, Madan Mohan Malaviya, an important leader in the Indian freedom struggle, established Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi.

However, after the liberalisation of the Indian economy in the early 90s, in the era of services and export-oriented led growth, focusing on cities near ports, the city fell off the map, politically, economically, and educationally, like all other parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Narendra Modi’s candidature in 2014 not only brought the city into focus, but also triggered definitive aspirations among the people about a significant turnaround from this moribund development scenario. How did these hopes and aspirations pan out? The situation on the ground gives some indications.

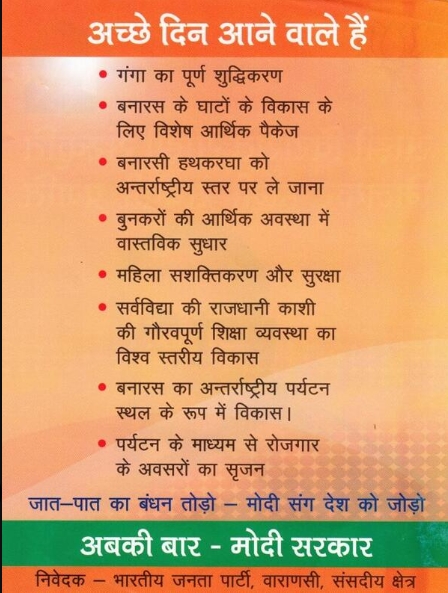

Hope in 2014: The Promise of Transformation

I am sitting with Rudra, a Hindi postgraduate who now runs a book cafe in Varanasi. Pondering about the time he heard about Narendra Modi contesting from Varanasi, he says he was enthusiastic when he heard the news. His enthusiasm was primarily linked to what he had heard about the Gujarat Model of development, and he was keen to welcome the maker of that model to his constituency. For him, like many other city residents, it was a unique moment in the city’s political history as they would be voting for an MP who was a favorite to become the Prime Minister of India.

He hoped that the Prime Minister representing the city would help transform the city’s infrastructure. As a former student of the Banaras Hindu University, the famed university run by the Central Government, Rudra hoped that the university would benefit from his tenure. Around 2014, he felt that the university was becoming a budding ground for hooligans, who vitiated the academic environment in the city.

Ganga ghats play an integral part in the lives of city residents. Students from the Banaras Hindu University visit the ghats almost everyday in the evening, walking along the river Ganges, immersing themselves in the unique cultural traditions practiced along the river. He had hoped that the cleanliness of the Ganges would improve. Praveen, who works as a tutor in one of the famous coaching centers of the city, contested the last assembly elections from the Rohaniya constituency, a semi-urban constituency of the Varanasi Parliamentary constituency. His experience has led him to believe that elected representatives have limited means to provide basic facilities to people, namely, roads, electricity, and water. He believes that the real power of an MP lies in escalating issues of local importance at the national level. The funds available to an MP for the development of the local area are paltry and can only provide for small fixes here and there.

Praveen is right. It would be unfair to assess Narendra Modi’s tenure on the local infrastructure and its messiness, even though his ardent believers, pejoratively referred to as Modi Bhakts, credit him for that. When Modi’s name was decided as the local MP, the people believed that given his extensive experience of 13 years as the Chief Minister of Gujarat, then advertised as the model state for the Nation’s progress and the pioneer of the Gujarat model, he knew what it takes to transform the city and make it a model city for the rest of India. Given the euphoria around the Gujarat Model, even detractors believed that he knew what it takes to change the face of Varanasi and make it a development capital.

Kyoto of India: An Unfulfilled Dream

His term started with the promise of developing Varanasi along the lines of Kyoto city in Japan. Kyoto, one of the oldest municipalities in Japan, is considered Japan’s cultural capital. A delegation of officials from Varanasi, including the then District Magistrate and the city Mayor, went to Japan to study various aspects of the city, including its development paradigms. Ten years later, even the BJP’s workers have stopped talking about the project. It has become a joke amongst the political opponents of the BJP. It has become a phrase used to tease BJP supporters and workers during discussions at the various tea stalls in the city, an integral part of socializing among the city’s male population.

It is difficult to pinpoint the precise period when PM Modi or his team realized the impossibility of this goal. Developing Varanasi as a template city centered around its ancient culture and religion, which other old Indian cities, like Ujjain, etc., can emulate, no longer seems to be the aim.

After 10 plus years of reign as a local MP, which coincides with 7 plus years of BJP rule in Uttar Pradesh State government, the so called Varanasi Model of Development is elusive. Given the failure of this promise, a fair assessment begs this question of a precedent elsewhere. Are there any precedents from the recent decades of a city’s transformation in 10 years?

Related: Homeless in Prime Minister’s Varanasi…

Noida transformed into a major hub in North India for the IT services industry. Along with Greater Noida, it has become a major industrial city of Uttar Pradesh. The city saw massive growth in population and infrastructure during the rule of Mulyalam Singh Yadav and Mayawati between 2002 and 2012.

The Gomti Nagar area has developed as a modern satellite town area in Lucknow, the state capital of Uttar Pradesh. Ghaziabad’s Indirapuram area witnessed the same massive growth during 10 years between 2002 and 2012. Varanasi has not experienced any such development.

Employment Woes: A Tourism Story Gone Wrong

The Varanasi story in the ten plus years of the Modi years is just like the rest of India. These years have not led to any increase in formal employment opportunities in Varanasi. The city has failed to become the center of any formal business activity, integrating it with manufacturing or services exports. The growth witnessed by Noida or Gurugram in the IT services sector in less than a decade is significant. But, Varanasi, despite being the PM’s constituency, has not attracted any significant private investment, in services or manufacturing. Startup India, the flagship scheme of the Modi Government, did not gain any momentum in Varanasi. The incubation centers in BHU & IIT BHU remain moribund.

Post-Covid, there has been a surge of tourists and pilgrims to Varanasi. However, the composition of tourists matters for the tourism economy. The promise was to make Varanasi an international tourist destination, but Varanasi is far from becoming an international tourist destination. India, cumulatively, received 9.5 million foreign tourists in 2023. According to the state tourism report, Varanasi region received 0.22 million foreign tourists in 2023. That number was 0.33 million in 2017. In 2023, 17 million international tourists visited Istanbul, and nearly 26 million international tourists visited Bangkok, Thailand.

A tourist with a high propensity to spend and to stay multiple days in a city contributes far more to the local economy than a low-spending, day or overnight traveler. Even though Varanasi attracts a huge number of tourists, most comprise domestic tourists, often from nearby regions. In 2023, foreign tourists comprised only 0.17 % (2.2 Lakhs) of nearly 13 crore tourists who visited the Varanasi region. A typical foreigner does a one day trip in Varanasi, comprising of a boat ride, watching Ganga aarti, and a visit to Sarnath. Ten years on, no new tourist attraction has been added to this itinerary, either in Varanasi or in nearby districts, that can extend the stay duration by days. Local tourists add mostly to the demand for local travel, leading to a large increase in auto-rickshaw drivers, or temporary food stalls selling low-priced items. Both these jobs provide low upward mobility and practically no prospects of high-income opportunities in the future.

No new shopping mall has come to the city. Existing ones often have vacant shops and the city has no multiplexes that are part of a pan-India chain, indicating a lack of demand for expensive shopping or entertainment experiences.

To gauge the lack of meaningful job opportunities for the young in the city, all one needs to do is talk to any young driver of electric auto rickshaws, which have grown huge in number. You may easily stumble upon a university graduate driving one. This reflects the painful reality of the Modi years. A reality marked by claims of impressive GDP growth but with huge unemployment.

Part 2 of the series follows on 27 January 2025.

Excellent piece