Marx’s Fear of Growth

Reading Kohei Saito’s Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism (Part – 2)

For a long time, the term Ecological Marxism seemed like an oxymoron. It was only in recent years that serious inquiries into the ecological dimensions of Marxist thought began to take shape. Among those who made significant contributions to this field, only a handful—John Bellamy Foster, Paul Burkett, Brett Clark—stand out. The reason why Ecological Marxism was once considered paradoxical lies not only in the ideological rift between environmentalists and traditional Marxists but also, crucially, in Marx himself.

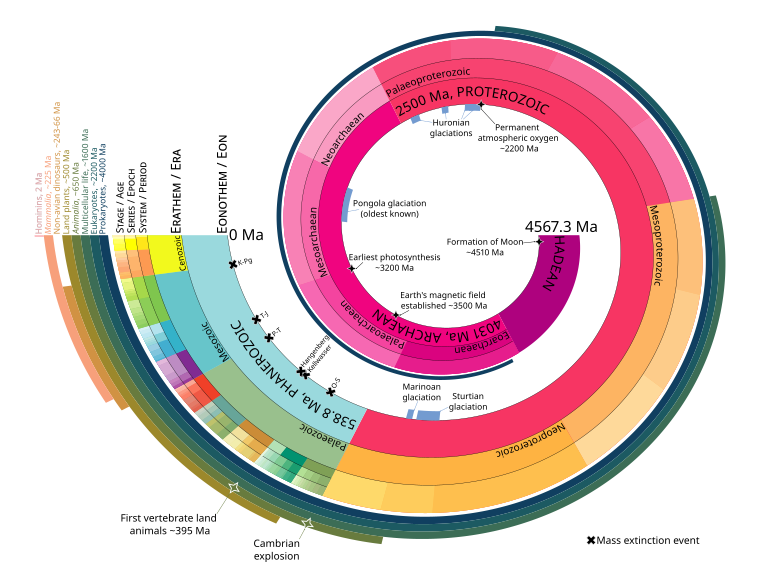

As explored in the earlier parts of this series, the productivist approach—the hallmark of classical Marxism—has been increasingly exposed as inadequate for addressing the economic and ecological crises of the Anthropocene. It is now becoming evident that any attempt to resolve the contemporary crisis without abandoning production-centricity is bound to fail. The metabolic rift between humanity and nature, exacerbated by relentless industrial expansion, cannot be healed through a mere acceleration of existing trends.

Kohei Saito argues that Marx was, in fact, conscious of these contradictions as early as the 1860s while writing Capital. However, his unwavering faith in historical materialism—the idea that human history is driven by the development of productive forces—led him to view the revolution as an inevitable leap, where capitalism’s own internal tendencies would be pushed to their extreme, culminating in communism. This Promethean vision of history reduced the revolutionary transition to a mere intensification of capitalism’s contradictions.

Marx’s own words reinforce this notion:

“No social order ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed… and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society.”

(A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859, MECW 29: 263)

Citing this passage, Saito highlights how deeply ingrained this belief was in Marx’s early work. However, he also argues that Marx later made a determined effort to escape this theoretical deadlock. A careful study of his later writings and notebooks, many of which have been published in the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), reveals a significant evolution in his thought. As someone who has worked closely on editing MEGA, Saito is well-positioned to make this claim.

Through MEGA, we can trace a pivotal shift in Marx’s critique of capitalism—particularly in his unpublished economic manuscripts, which were compiled in the second section of MEGA. In fact, recent years have witnessed a surge in attempts to reconstruct a late Marx based on these materials.

After publishing Capital, Marx devoted intense study to two major areas: natural sciences and pre-capitalist, non-Western societies. Based on MEGA, scholars such as Kevin Anderson (2010) and Karl Eric Vollgraf (2016) argue that Marx’s engagement with the natural sciences helped him refine his critique of environmental degradation under capitalism, while his break from Eurocentrism in the 1870s marked a decisive departure from his earlier Prometheanism.

It is in this intellectual transformation that Saito discovers the ecological Marx. By rejecting ethnocentrism and productivism, Marx fundamentally revised his earlier materialist conception of history, leading to a crisis in his worldview. His final years, according to Saito, were marked by an intense effort to reconstruct historical materialism from an entirely new perspective—one that opened the door to alternative visions of post-capitalist society.

After 1868, Marx’s rigorous investigation of non-Western societies led him to recognize the revolutionary potential of communal property structures. His letters to the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich vividly illustrate this shift. However, Saito warns against interpreting Marx’s study of Russian communes in isolation. Instead, his intellectual exchanges with Russian thinkers such as Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Maxim Kovalevsky enriched his vision of communism beyond the Western European framework.

For Marx, theorizing an alternative society required a complete integration of political economy with his broader intellectual engagements. A deeper analysis of why he spent the last 15 years of his life studying both pre-capitalist societies and natural sciences opens up fascinating new possibilities for interpreting his letters to Zasulich. Through these writings, we can begin to unearth a radically different Marx—one who rejects unchecked, limitless growth and envisions a degrowth communism.

To truly grasp Marx’s final vision of a post-capitalist society, we must look beyond Capital. For Marx himself, Capital remained an unfinished project.

The study of his economic manuscripts and scientific notebooks brings forth a Marx who is strikingly different from the conventional image of him. According to Karl Eric Vollgraf, Marx came to recognize the value-generating role of nature in the production process, prompting him to rethink the labour theory of value. However, as scholars like Heinrich and Vollgraf argue, the sheer scope of this theoretical reconsideration was so vast that Marx was unable to complete it before his death.

Saito further notes a major theoretical rupture in Marx’s thought following his analysis of real subsumption in the Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63. After this point, Marx began to fundamentally rethink his earlier assumption about capitalism’s progressive character. Like Hegel, early Marx had been an ardent defender of history’s linear progress, believing that the contradictory development of productive forces—though initially destructive—would ultimately lead to human emancipation. However, in his later years, Marx came to realize that under post-capitalist conditions, productive forces would not automatically provide a material foundation for liberation. Instead, they would accelerate the plunder of nature.

(To be continued…)

Translated from Malayalam by Sania KJ

Click Here to Read Part 1

Oh.. really from this only I am aware of another side of Marx!

Eagerly waiting for the next article