On the eve of the presentation of the Union Budget, development professional Dr. Varsha Pillai, underscores the importance of incorporating feminist intersectional policies into our economic planning paradigms. She points out that the Doughnut Economics model advanced by Economist Kate Raworth would give valuable lessons, guidance and direction to this exercise.

India’s development trajectory has for long faced the challenges of poverty, inequality, environmental degradation and social exclusion. It has also been the country’s experience that conventional economics often overlooks and undervalues crucial aspects of economic activity and value creation such as unpaid labor, caregiving and community work, aspects that are important in nation building and mostly performed by women. With assumptions focused on rational independent actors making free choices, conventional economic models fail to account for structural inequalities and social constraints that inevitably affect economic decision-making. With GDP growth and market efficiency being the core metrics of economic success, conventional economics does not consider broader measures of well-being, including quality of life and sustainability.

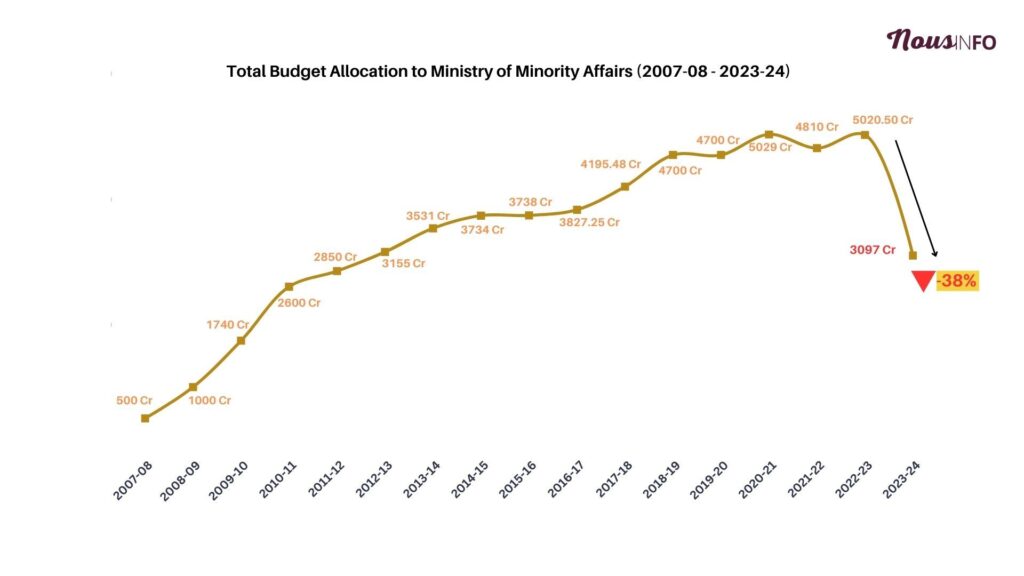

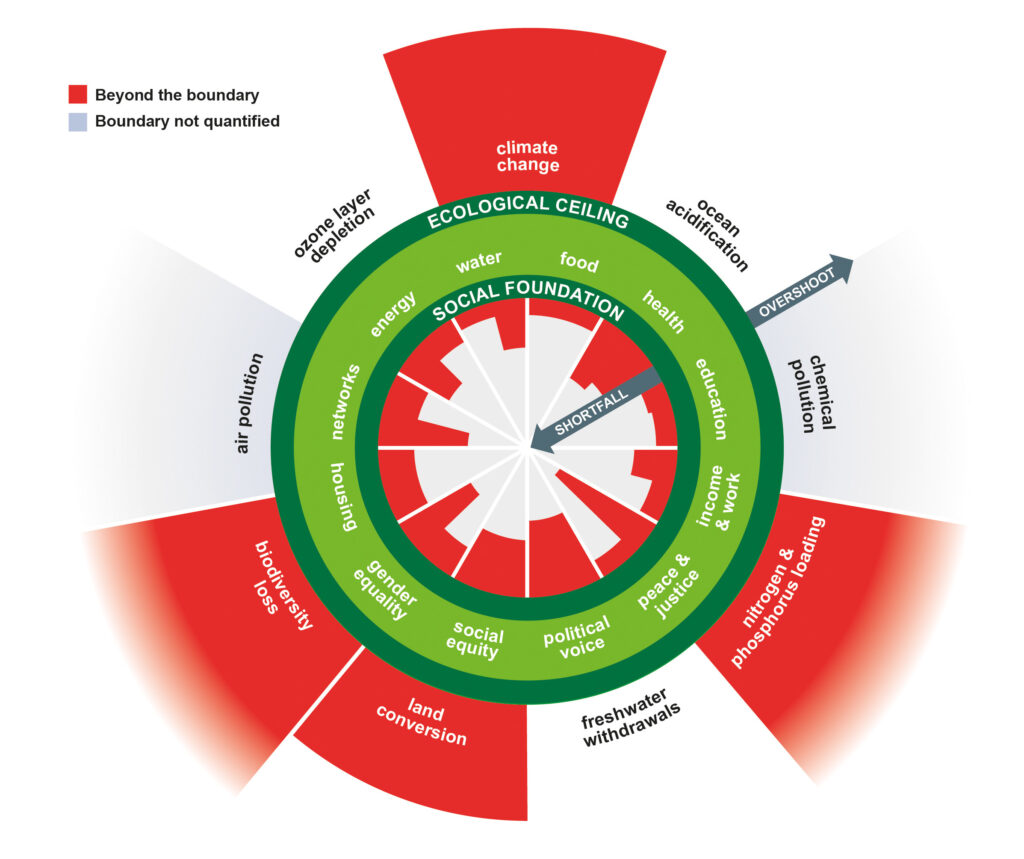

In this context, there is a case emerging for looking at other economic models that challenge conventional economic thinking, where activities like childcare, elder care and household management are viewed as fundamental economic contributions and are integrated into economic planning. The Western model of development has led to severe environmental costs resulting in massive carbon emissions and contribution to climate change and continued depletion of natural resources. We have also seen Western economies suffer from extreme wealth concentration, growing inequalities and marginalisation of vulnerable groups, especially women and minorities. The Western model has also revealed certain structural weaknesses with its over-reliance on debt-driven growth, boom-bust cycles causing economic instability, excessive consumerism and waste creation and over-dependence on unsustainable resource extraction.

As we try to find an economic model that ensures that India does not repeat all the mistakes of the western economies, Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model, particularly its feminist intersectional principles, can help offer a compelling framework for inclusive and sustainable development in the Indian context. The economist, Kate Raworth’s journey towards developing the Doughnut Economics model is a fascinating example of how new economic thinking can emerge from questioning established frameworks. Armed with a questioning mind, Raworth’s path began during her work as an economist at Oxfam in the 2000s, where she directly encountered the challenges of global poverty and environmental degradation.

Her experience led her to question conventional economic models and metrics while studying economics at Oxford University. She began to critically examine the limitations of GDP growth as the primary measure of economic success and observed that while many countries achieved GDP growth, they simultaneously experienced increasing inequality and environmental deterioration. This further sparked her interest in seeking a more holistic model that could account for both social and environmental boundaries. Raworth first publicly presented her model in a 2012 Oxfam discussion paper, which gained significant attention and led to her developing these ideas further in her 2017 book “Doughnut Economics.”

Interestingly, the Doughnut model’s feminist foundations resonate deeply with India’s socio-economic realities. By emphasizing social equity, intersectionality and gender justice, this framework addresses systemic barriers that have historically marginalized vast sections of Indian society. The model’s recognition of unpaid labor is particularly significant in India, where women perform an estimated 297 minutes of unpaid care work daily compared to men’s 31 minutes. The recognition of unpaid labor could transform economic policies, especially in relation to the contribution of Indian women to the care economy, of which household maintenance, childcare and elder care are key components. These crucial components remain invisible in conventional economic metrics. When unpaid domestic labor is incorporated into economic calculations, there is a distinct possibility of the creation of policies targeted to better address gender inequalities. This could also lead to a support infrastructure, which would reduce women’s unpaid work burden.

The Doughnut model’s emphasis on social reproduction challenges conventional economic thinking, where conventional development metrics tends to focus overtly only on GDP growth while overlooking the essential work of maintaining households, communities and social relationships. India has the distinction of the role played by social bonds which plays a crucial role in enabling economic resilience, acknowledging the importance of this could lead to effective and enhanced poverty alleviation and social security programs.

India’s complex social fabric, woven with caste, class, religion, and regional identities, makes the intersectional approach particularly valuable. The model helps identify how multiple forms of discrimination interact and affect different groups. For instance, Dalit women face unique challenges at the intersection of caste and gender discrimination, requiring targeted policy interventions that conventional economic models overlook.

Implementing the Seven Principles in India

Evidently, the principle of inclusivity deeply aligns with India’s constitutional values. It can also strengthen existing affirmative action programs, especially while extending them to new areas of economic participation. Another key principle around social equity considerations can potentially support and help redesign welfare schemes to reach the most marginalized, addressing not just income poverty but also access to education, healthcare and economic opportunities. Furthermore, even as we witness a push-back from developed countries around gender policies, the Doughnut Model’s gender justice principles could help India by way of supporting the transformation of sectors like agriculture, where women comprise 75% of the workforce but own only 13% of land. The implementation of Doughnut Model’s gender justice principles would be particularly significant in terms of promoting land rights and access to resources.

Within the environmental domain, India would gain by learning how the Doughnut model’s environmental ceiling provides achievable and measurable ways to outcomes. For instance, women in India’s villages need to be seen as primary resources managers since they possess valuable real world knowledge about sustainable practices. These practices and their varied experiences have the potential to not just inform climate adaptation strategies but can also help in the formation of natural resource management policies.

Just as there are enough ways to implement the Doughnut model in India, we must also understand that its implementation can face several challenges beginning with institutional resistance to recognizing unpaid work and big push-back from certain lobbies interested in maintaining the status quo of deep-rooted social hierarchies that perpetuate inequalities. Another big obstacle emerges in the form of lack of real data around intersectional experiences. Further, since this model requires the upending of the existing way of looking at the economy, it will also face resource constraints in implementing comprehensive programs.

However, within these challenges we must also see opportunities. Could India given its still vibrant civil society, growing digital infrastructure and existing social welfare frameworks create a foundation that could help implement the Doughnut model’s principles? The way forward could work if we proactively engage with policymakers and urge them to invest in the creation of mechanisms that value and support unpaid care work. Further we will need to advocate for the creation of systems that could develop intersectional data collection methods to better understand overlapping vulnerabilities. Enable policy making to inherently design policies that explicitly address multiple forms of discrimination even as it strengthens participatory governance to include marginalized voices in economic decision-making. Raworth’s feminist intersectional Doughnut model offers India a pathway to development that is both inclusive and sustainable. By recognizing the interconnected nature of social, economic, and environmental challenges, it provides a framework for policies that can address India’s complex development needs while ensuring no one is left behind.