‘Vikasanam’ Sans Memories

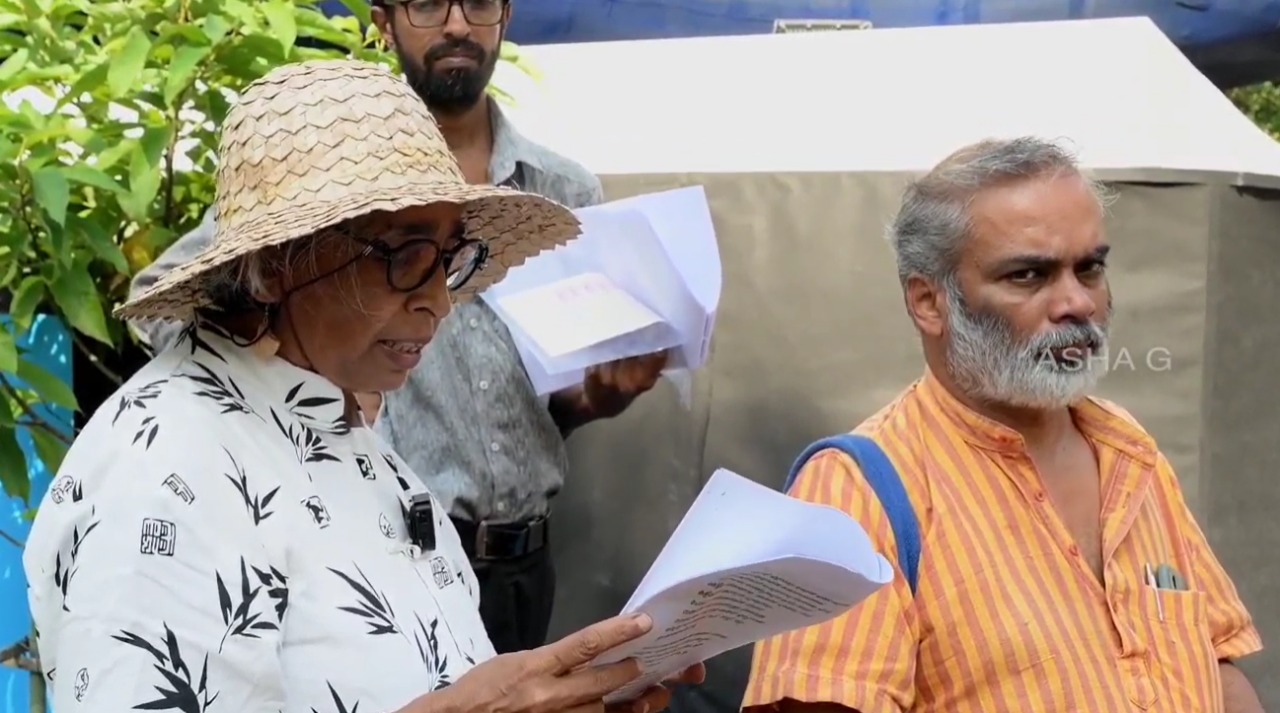

International Biodiversity Day was observed on May 22, 2025. Kerala too had some functions on this day. However, the observance also raised questions as to how committed we are as a society to the concerns related to biodiversity. In this first person account, writer and neuroscientist Asha Gopinathan draws from her life and experiences to look at some so called development oriented events in Kerala wondering whether it upholds the concepts of biodiversity.

In October 2012, my mother and I took a journey.

She was already in her eighties then—Dr. K. Saradamoni, a social scientist whose hands had gathered decades of fieldwork, whose eyes could read both statistics and silences. That autumn, she held my hand as we climbed the weathered stone steps of Hampi. The river Tungabhadra flowed behind us, wide and brown like old silk. We crossed it by boat, and later, at our guesthouse—called Mowgli—we sat on a porch looking out at paddy fields. In the distance, the river shimmered. At night, the darkness was alive—with frogs crooning from the edges of the paddy fields, their voices rising like small, insistent prayers. No hoardings, no headlights, no loudspeakers—only the ancient chorus of a land allowed to breathe.

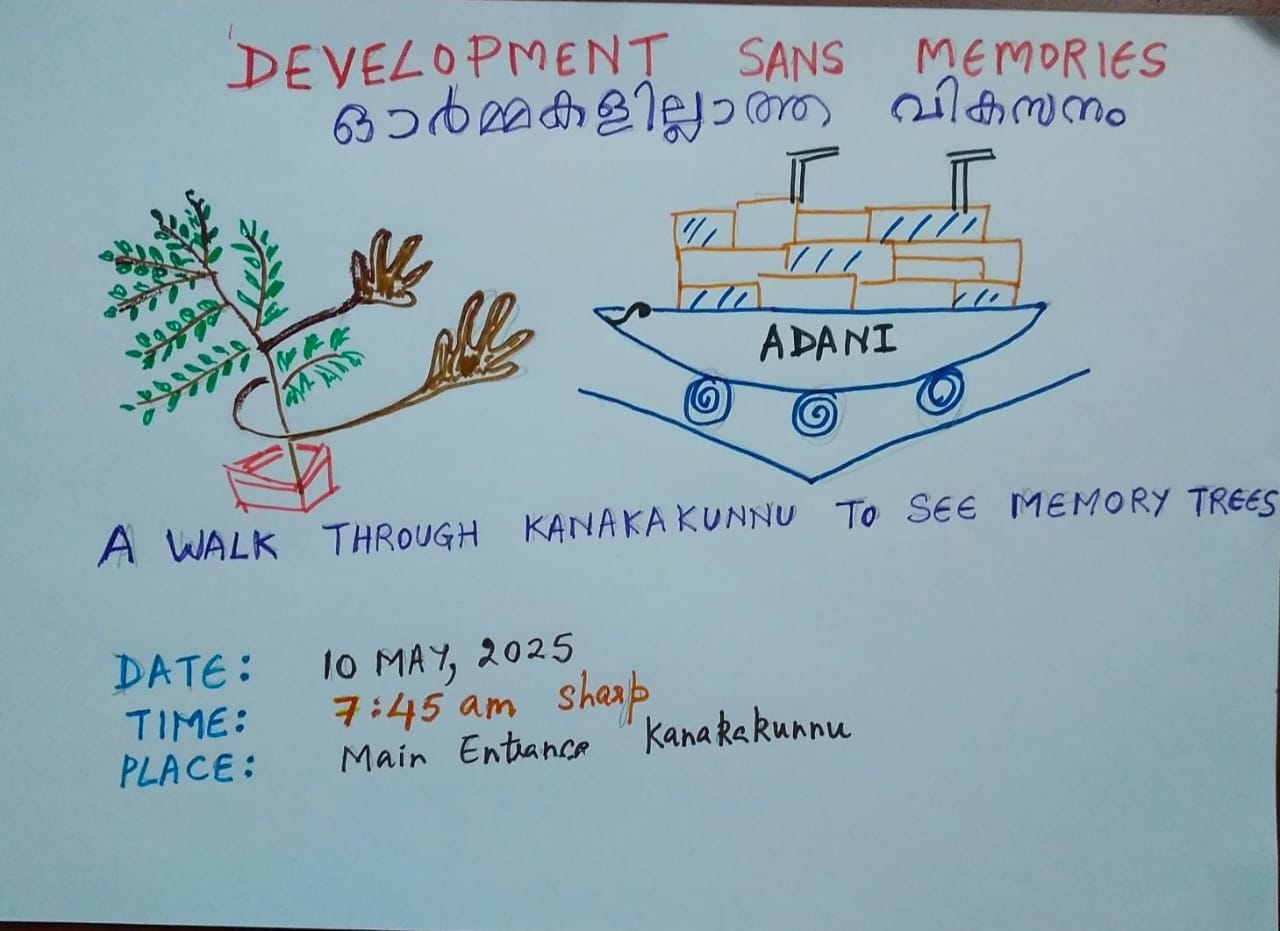

She wrote about that trip the next year, in August 2013, in a Malayalam article titled Krishi, Tourism, Vikasanam— “Agriculture, Tourism, Development.” I found it recently, folded neatly in a book, her handwriting curling into the margins. That day, I read excerpts from it aloud at a Memory Tree Walk I organised at Kanakakunnu Palace grounds in Trivandrum.

We had planted three trees there in October 2021—my sister and I—in memory of our parents and grandmother. A jamun, a mango, and a chempakam (Magnolia champaca) for Amma. That day, I also pointed out two other trees, planted by others in remembrance. But unlike what many Trivandrum residents may imagine, Kanakakunnu is far from ideal for nurturing memory.

There is no water source nearby. The only taps are in the bathrooms, so I carry buckets back and forth across the palace grounds to water them. The mango sapling was once damaged by a Christmas prop. The jamun, twice, was pushed under a temporary police control room. Each time, I feared we had lost them. But with the help of Binu Maash, a Vriksha Ayurveda expert, we brought them back to life. He understands what trees need—light, shade, silence.

The chempakam, my mother’s tree, had been spared. Until now.

A large shipping container has been installed inside the heritage grounds—a promotional installation for the Vizhinjam seaport project. It has been placed right against the chempakam’s tree guard. Had it not been for that thin barrier of iron, the tree would likely have been chopped. Two massive floodlights now beam directly at it, casting an unrelenting glare day and night. The tree has begun shedding more leaves than usual. It is stressed. I can tell.

This is not just carelessness—it is a violation.

The matter of Kanakakunnu has been sub judice since the controversial nightlife project was proposed two years ago. There is also a High Court order that clearly prohibits the erection of billboards, flags, or installations in public spaces. And yet, here it is—metal, wires, and arrogance—planted without permission.

Kanakakunnu is not just an event venue. It is an INTACH-certified Grade A heritage site, including its grounds. Any change to the landscape, any structure, any installation—must be cleared by the Arts and Heritage Commission. The Tourism Department, which took over the property from the PWD, did not seek such clearance. They simply acted.

They treat the grounds as a revenue-generating stage—renting it out for fairs, exhibitions, festivals. After every event, the earth is bruised: cables knotted around tree trunks, waste scattered across the lawn, delicate saplings crushed under careless feet. They forget that this is not a venue, it is a living space.

Recently, MLA V.K. Prashant spoke to the Tourism Department. They have now instructed the agency to remove the container. But will it stop here? Or will we have to fight this again—next season, next festival, next “development” dream?

What we need now is not just promises, but vigilance. A citizens’ committee—people who love this land, who watch, who remember—must speak up again and again. Because this is not only about a tree. It is about the ownership of the commons. It is about memory, and who gets to shape it.

Two years ago, we surveyed visitors to Kanakakunnu. Over 90% said they wanted green space—not concrete, not chaos. They came for trees, not towers. But their voices are drowned in the machinery of tourism. The Department dreams of footfall; we dream of footsteps softened by grass.

My mother would have seen through it all. She always did. In her Hampi reflections, she asked—why do we think a place is “undeveloped” simply because there are no shopping malls, no high-rises, no traffic jams or neon lights? She praised the guesthouse owners for building something beautiful without destroying lakes, without flattening hills.

That was her definition of vikasanam—not conquest, but care.

Now, her tree stands under a harsh spotlight, its leaves curling, its roots disturbed. And yet it stands. I see her in its quiet resistance.

Kerala could learn from this. We could grow differently—if only we listened to the land, and to those who loved it.

Sometimes, in the late evenings, I walk to the chempakam, place my palm against its bark, and wait. If you listen closely, you can hear the memory rustle in the leaves.

And in that rustle, a question: Is this development?

And still, no answer.

Only the soft hush of falling leaves.

Watch the full video from the latest Memory Walk below:

Did anyone reach out to you from the government or municipality . Curious to know

No. I reached out to several people and now that the fair Ente Keralam is over, the boat has been removed.

Well researched and sensitively handled ! Thought provoking as well. Enriching write up dear Asha.