Senior Journalist and author Nalin Verma’s fortnightly column in The AIDEM titled ‘Everything Under The Sun’ continues. This is the second article in the column.

“We are Hindus. My Dad had a Muslim as his bosom friend who often visited our home. My mother, however, would serve tea to the Uncle in a ceramic cup, while my father got his in a steel cup. Yet, both Dad and Uncle sipped their tea without any fuss, enjoying their usual gossip and banter.”

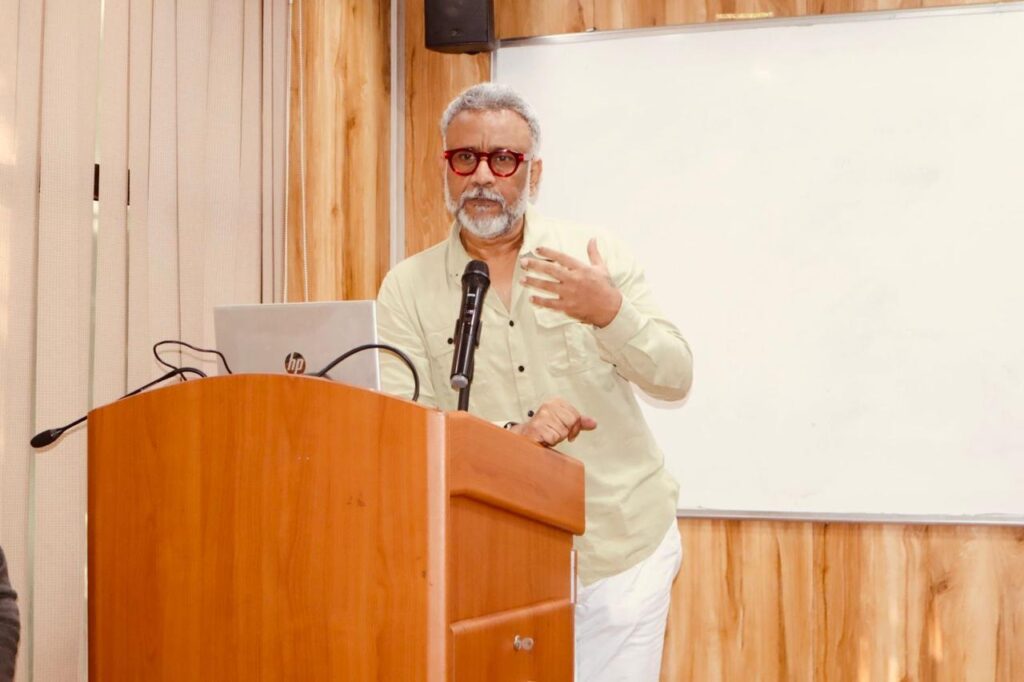

This was how Anubhav Sinha began narrating the journey of his life.

Anubhav, who has achieved stardom in Indian cinema with a series of socially and politically poignant films like Ra.One (2011), Mulk (2018), Article 15 (2019), Thappad (2020), Anek (2022), Bheed (2023), and his latest, IC 814 – The Kandahar Hijack (2024), was addressing students and scholars at Jamia Hamdard University, New Delhi, on December 7.

The sensitive director, producer, and writer, aware of the curiosity of students in the formative phase of their lives, chose to share his story in a way they could relate to. His speech on “Indian Cinema and Social Change” began with a deeply personal anecdote, recounting a dilemma he faced as a young adult.

“Why do you serve tea to Uncle in a ceramic cup and to Dad in a steel cup?” I once asked my mother. She replied nonchalantly, “Woh Musalmaan hain” (he is a Muslim). Your granny served tea or beverages to Muslim guests in ceramic utensils. Your great-grandmother did the same. I learned this custom from my elders.”

“So what if Uncle is a Muslim? He is Dad’s best friend. Why should he be served in a different cup?” I persisted. Eventually, my parents decided to serve tea to Uncle in the same kind of cup.”

Anubhav’s story reflects a practice that has existed in many Hindu homes of North India for generations—small, almost unconscious acts of “otherisation.” Yet, these moments rarely disrupted personal and social relationships between the two communities. They did not escalate into broader social conflicts either.

The question arises: when and how did the practice of serving tea or food differently to members of another community begin? After all, tea remains unchanged in taste or character, whether served in a steel or ceramic cup. Moreover, utensils like steel and ceramic cups likely became commonplace in dining traditions long after the emergence of Islam and Hinduism. So, how did the ancestors of individuals like Anubhav decide to serve the same beverage in different cups based on religion?

Social Constructs:

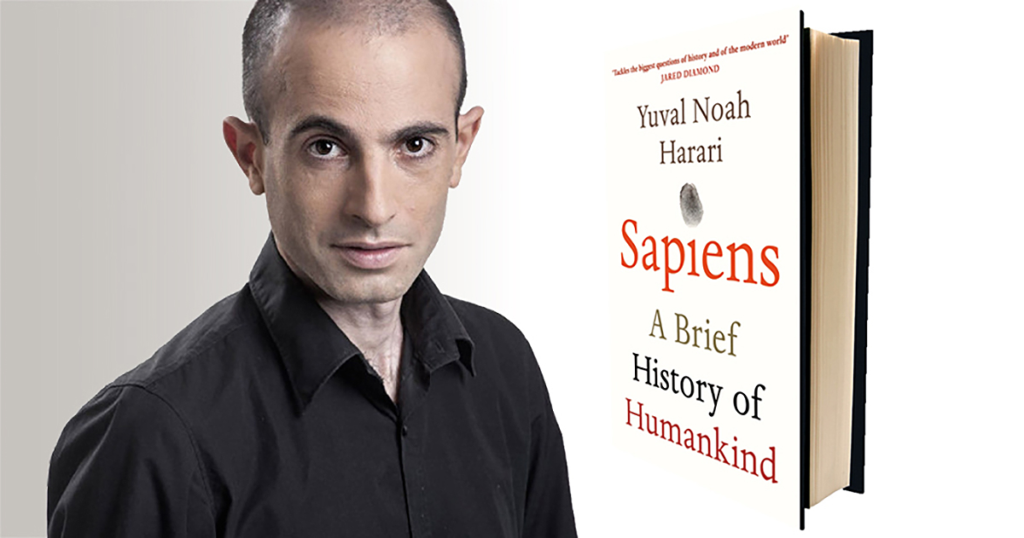

Charles Darwin, through meticulous empirical research, debunked the theory of divine origin of species and established that all species share a common ancestor. This groundbreaking idea sparked outrage among religious groups worldwide. Yuval Noah Harari, the modern historian and philosopher, took this further, asserting that concepts like God and nationalism are “myths” that unite people by shaping their collective imagination.

In his widely acclaimed book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Harari writes, “Large-scale human cooperation—whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city, or an archaic tribe—is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s imagination… States are rooted in common national myths. Two Serbs who have never met might risk their lives to save one another because both believe in the existence of the Serbian nation, the Serbian homeland, and the Serbian flag.”

A comparative analysis of Harari’s work, building on Darwin’s theory of natural selection and various empirical studies of human evolution, highlights that cultural, customary, and religious practices are social constructs. Harari goes further, pointing out how politicians—driven by their insatiable desire for power—exploit these “mythical realities” with destructive precision.

The Indian Context:

In 2015, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while addressing an election rally in Bhagalpur, Bihar, remarked, “The anti-nationals can be identified by their dress and attire.” Ostensibly, this targeted Islamic terrorists, but the underlying message sought to alienate Muslims, whose clothing differs from that of Hindus. Following this, Hindutva zealots picked up the cue, identifying minorities based on their distinctive dress and eating habits.

Speeches delivered by Hindutva extremists, often disguised as religious leaders, in gatherings such as Dharm Sansads and Kumbh Melas, amplified such divisions. These inflammatory statements, delivered in cruder language, fueled unrest and destruction across India. Yet, these divisions served the political agenda of the Sangh Parivar, solidifying their power.

Back to Anubhav Sinha’s Story: In Anubhav’s anecdote, serving tea to a Muslim guest in a separate cup was once an innocuous social practice, confined to the boundaries of local society. However, when the political class—particularly those wielding radicalism as a means of control—amplify such differences, they drive deep wedges into society. By exploiting myths and collective imagination, they turn subtle cultural nuances into tools for division, all to serve their political ambitions.

Uniqueness of Indian Spiritual Tradition

The works of Darwin and, more recently, Harari have caused outrage in much of the monotheistic world. Yet, these theories have made little impact in the Indian subcontinent. It’s not that Indian saints—whether from the Sanatan tradition or the Islamic one—have accepted Darwin’s or Harari’s ideas about human evolution. Instead, Indian spiritualists have consistently questioned numerous social constructs that emerged at various stages of humanity’s development.

Saint Kabir, for instance, was a pioneer in exposing and ridiculing the societal divisions between Hindus and Muslims. One of his verses highlights this beautifully:“Jo tu Babhan-babhani jaaya, aani dwar kah-e nahin aaya / Jo tu Turuk-Turukini jaaya, bhitare khatna kah-e na karaya”

(“If you were begotten by Brahmin man and woman, why didn’t you arrive from a separate path? And if you were born to Turuki parents—Muslims, as referred to in the Varanasi folk lingo—why weren’t you circumcised in the womb itself?”)

In essence, Kabir emphasized the shared origin and evolution of all human beings, regardless of their religious labels.

Kabir’s sentiments echo even older ideas rooted in Vedic tradition. The dialogue between King Janaka and the sage Ashtavakra—whose body was distorted in eight places—also confronted societal norms and spiritual misconceptions. This dialogue, preserved in the Ashtavakra Gita, was later explored extensively in a series of discourses by Osho Rajneesh.

Even modern philosopher-poets have questioned divine constructs while remaining anchored to spiritual inquiry. In his celebrated Shikwa, Allama Iqbal challenges the Almighty:

Tujhko maloom hai leta tha koi naam tera

(“Did anyone even know Your name before the advent of mankind?”)

Mirza Ghalib, meanwhile, injects humor into such existential musings, quipping:

Hamko maloom hai jannat ki hakikat lekin / Dil khush rakhne ko Ghalib ye khayal achha hai

(“I know the reality of heaven, but this thought is good for keeping the heart entertained.”)

Indian Cinema and Social Change:

Instead of delving into his films—Ra. One, Mulk, Bheed, Article 15, and Thappad—Anubhav Sinha chose to share a more personal anecdote at Jamia Hamdard University. He explained what brought him to the campus: the invitation of his friend, Vice-Chancellor Prof. (Dr) Afshar Alam, for a delicious lunch. Both Anubhav and Afshar are alumni of Aligarh Muslim University.

“He (Afshar) knows my weakness for good food. I couldn’t say no when he lured me with a tasty meal,” Anubhav joked. Afshar responded warmly, “I’ll keep inviting him with good meals to bring him back to campus.”

Their light-hearted exchange carried a subtle but profound message: while Anubhav’s father had once served tea to a Muslim friend in a separate ceramic cup, today, Anubhav and Afshar shared their meal on the same plates.

Anubhav’s films embody this very spirit. They challenge destructive societal dogmas, but in a style that resonates with younger generations. His narratives raise serious questions in a seemingly lighthearted, accessible manner—an approach that mirrors his own lifestyle. This blend of engagement and depth is what makes his work widely accepted and successful.

I am not aware of Mr. Anubhav Sinha’s work, so my comments have their own limitations. However, the title “Questioning Construct: Spirituality, Society, and Cinema” covers a larger domain, so there is a need to expand the elaboration further. Jumping Darwin to Modi is a wider gap, difficult to cover even by a Hanuman.

I hope Anubhav has not failed to notice that in many Hindu Households, cooking of non-veg was not allowed inside the main kitchen and it was also consumed outside the main dining place. There must be something common between the two practices: serving tea to a Muslim Friend in a ceramic cup and cooking and eating non-veg at a separate place even by the members of the same family. Therefore, there is nothing related to Hindu-Muslim here. I do not know if his mother served tea to a Dalit guest in the same steel cup.

Darwin was a genius to see the link between different species as a development process but in the end, everything is nothing but a different construct of the tiny particles, electrons, protons, and neutrons. As a result, a synthesis between the religion and the science is not impossible.

The practice of using a separate set of utensils for non-Muslim friends in villages reflects deep-rooted social and cultural dynamics that can stem from religious beliefs, traditions, or perceived notions of purity and dietary restrictions amongstmany Muslimfamiles. In some communities, it is tied to the idea of maintaining ritual cleanliness or avoiding cross-contamination of food habits, particularly when religious codes like halal play a significant role in daily life. Such practices may be accepted as part of cultural norms in some areas. Promoting dialogue, education, and mutual understanding can help address these practices in a way that respects tradition while encouraging inclusivity and communal harmony.

. At his Hibbert Lectures in the early 1930s , Tagore told his Oxford audience, with some evident pride , that he came from “a confluence of three cultures Hindu, Mohammedan and British “, this was both an explicit negation of any sectarian confinement, and an implicit celebration of the dignity of being broad based rather than narrowly sequestered . Religious identity can be rightly distinct from political self recognition.🙏