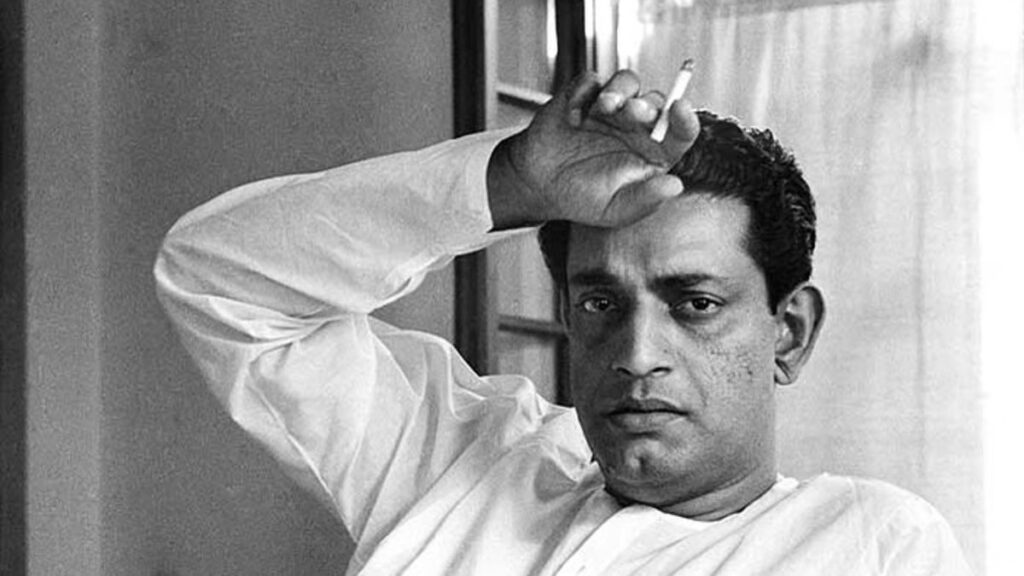

Satyajit Ray never shouted politics, but he never stayed silent either. His lens captured lives the system ignored, baring the myth of progress with quiet urgency. Pather Panchali wasn’t a plea for pity; it was a poetic rebuttal to state-sponsored dreams. While others marched with manifestos, Ray sculpted dissent in silences and shadows. His cinema didn’t argue, it revealed. Beneath the elegance of his frames lay a slow-burning resistance, asking: what if the story of India wasn’t the one we were told? As connoisseurs of good cinema across the globe observed the maestro’s 104th birthday on May 2, writer, film aficionado and socio-cultural observer V Vijayakumar presents a three part series that studies Ray films from a unique perspective. This is the first of the three part series.

Satyajit Ray’s cinematic politics remains largely uncharted, defying extensive scrutiny. In comparison to prominent Bengal directors like Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen, known for overtly political filmic expressions, Ray exhibited a discernible reticence toward overt political discourse within his cinematic realm. A closer examination unveils the political content even within Ray’s casual remarks and critiques regarding his cinematic creations. Works such as “Pather Panchali,” “Aparajito,” “Apur Sansar” (Apu Trilogy), “Devi,” “Charulata,” and “Mahanagar” (Women’s Trilogy), “Pratidvandi,” “Seemabaddha,” “Jana Aranya”(Calcutta Trilogy) deserve a political lens for optimal comprehension.

Recall Nargis Dutt’s assertion that Ray’s cinematic work served as a vehicle for disseminating India’s economic deprivation on the global stage. A quarter of a century following the premiere of “Pather Panchali,” the iconic lead actress of Bollywood’s “Mother India,” delivered a parliamentary address, which is often regarded as Bombay’s retort to Ray’s creation. This event marked a clandestine articulation of sentiments within India’s privileged echelons—a resolute, unequivocal response. Pather Panchali received acclaim as an epitome of humanity at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival, elucidating the profound content of rural existence. But Pather Panchali cannot be found as a film that fights with the social system for the sake of humanistic values. Nor was it a narrative about rural Indian poverty in the broadest sense. Yet it angered India’s elite intellectual life. ‘This is the real thing, those thugs have been deceiving us for so long’ – the realization gained by the common people through Pather Panchali was not acceptable to the elites.

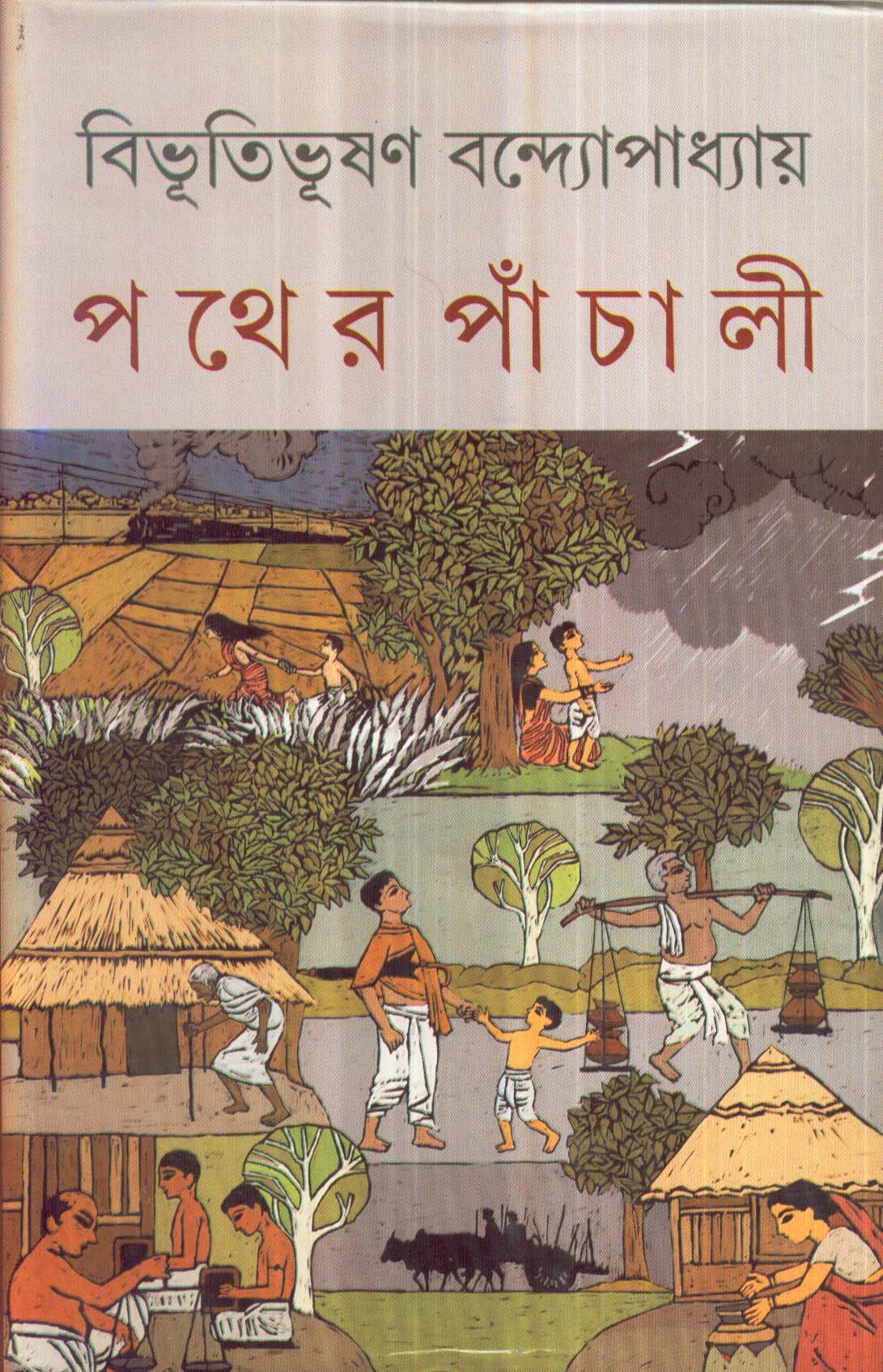

“Pather Panchali” unfolds in the fifties, conjuring the ambiance of pre-devolutionary times, coinciding with the clamor of slogans heralding planning and development under the native governance. The Awadi Conference of the Indian National Congress, Nehru’s socialist aspirations, Five Year Plans, and the Mahalanobis model pervaded the public discourse. The potential for actions to be swayed by the developmental visions of authority was substantial. During the film’s production, Ray grappled with dilemmas, necessitating outreach to the Bengal government for assistance. Financial constraints had temporarily halted the making of “Pather Panchali,” ultimately resuming with support from the Bengal government. Amidst discussions with Bengal Chief Minister Dr. B.C. Roy, regarding financing the film’s production, questions arose about the final scenes depicting Harihar’s family leaving their village. Roy inquired why the family was portrayed departing from their native land. Satyajit Ray, however, firmly resisted this suggestion. Before Ray could articulate his stance to the Chief Minister, Archana, a family confidante accompanying him, intervened in the dialogue. She argued that such an alteration in the film adaptation of Vibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s renowned work would distress numerous individuals, particularly the author’s spouse. Archana endeavored to persuade BC Roy, and she succeeded. Ray’s family confidante effectively shielded the film from governmental intervention driven by political motivations. Notably, “Pather Panchali” by Satyajit Ray exhibited hesitancy to embrace the prevailing developmental slogans of the establishment and the state. The film assumed a position of dissent. While “Pather Panchali” did not overtly articulate critical voices, it resonated with a fundamental protest against the system. The film distanced itself from the developmental ideology propagated by the reigning powers. This recalcitrant stance exposed “Pather Panchali” to the critical rebuff of the elite. Narrations portraying lives rife with adversity and affliction, whether in literature or cinema, perennially clash with the prevailing authority and the intellectual milieu under its sway.

Analyzing the Apu trio collectively, one can distinctly discern the parallel growth narrative of Apu mirroring the developmental trajectory of the nation. This observation beckons critical analysis, positing that these cinematic works inadvertently embed the prevalent ideological underpinnings of the developmental strategy of the system. Such critique is chiefly championed by the ‘committed’ critics, who perceive Satyajit Ray not as a political filmmaker but as an artist exclusively engrossed in cinematic technique and artistry. These critiques often manifest rigid, mechanistic stances, failing to grasp the nuanced tapestry of Ray’s creative vision. A comprehensive understanding necessitates an in-depth exploration of the development approaches propagated by the government during that specific period. It becomes evident that the prevailing development perspective was epitomized by the fervor to construct modern architectural marvels akin to Bhakranangal. Crucially, in those years, the fundamental tenets of development were seldom subjected to critical scrutiny. There existed a glaring absence of proactive examination, assessment of potential side effects, assimilation strategies, corrective measures, and transformative initiatives. The centers of power adhered steadfastly to a linear, tunnel-visioned approach to development, lacking the foresight to anticipate and mitigate unforeseen consequences. Contrary to this linear trajectory adopted by the power corridors, the narrative arc woven by Satyajit Ray in his films, particularly in the Apu trio series, deviates markedly. Ray eschewed the conventional narrative of linear progress and instead presented the lives of Harihar, Sarvajaya, and Apu as a complex tapestry interwoven with happenstance, fleeting joys, unexpected crises, and profound emotional breakdowns. Durga’s demise, abrupt village departure, existence with priestly father in Varanasi, father’s passing, mother’s occupation as a kitchenaid, reversion to familial abode with mother, her relentless aspiration for higher education conflicting with the father’s priesthood ambition, urban sojourn in Calcutta, the agonizing trajectory and eventual demise of Sarvajaya, a longing for literary pursuits, episodic writing endeavors, an inadvertent union with Aparna, Aparna’s passing, ensuing tumultuous phase, cessation of literary pursuits, and the eventual homecoming and reunification with his offspring — Apu’s narrative epitomizes an enduring saga of perpetual tribulations, wavering aspirations, and persistent scarcities, marked by tumult, disintegration, and resilient rebirths. Decidedly non-linear, starkly divergent from the contours of the state’s developmental chronicles.

Is the Apu trio engaging in a corrective endeavor regarding the state’s developmental narrative, endeavoring to steer it towards a more accurate trajectory? If so, it could be perceived as an alternative ‘Government mission.’ Observers point out the resemblance between Nehru’s policies and Soviet models, indicating a linear approach rooted in the socialist developmental ethos of that era. In this light, one might interpret Ray’s ‘state mission’ as a proposition for reevaluating socialist developmental paradigms, planning, and the public sector. Some posit that Ray’s work served as a cautionary signal to the administration. While Nehru’s policies and the Mahalanobis model were influenced by the Soviet Union, their alignment with the Bombay plan should not be underestimated. Notable instances of divergent approaches include efforts to consolidate World Bank influence in 1957 and the subsequent formation of the Aid India Consortium. The reality is that the concept of linear progress is more aligned with Western capitalist development than socialist ideals. This challenges the notion that Ray’s non-linear film narrative implies a developmental direction contrary to socialist concepts. Voices from the era, such as calls to address illiteracy in villages, Gora’s advocacy for reformers to identify with those needing reform, and Gandhi’s emphasis on India as a rural nation, resonate in Pather Panchali. Expanding on Chidanandadas Gupta’s profound insights, it becomes evident that Satyajit Ray’s initial conceptions of humanism, as depicted in Pather Panchali, undergo a transformation over time. Ray’s worldview progressively incorporates the deconstructionist tenets of Marxism, wherein he disengages from its prescriptive methodologies and rigid impositions. Implicitly, humanist artists like Satyajit Ray conveyed suggestions through their films on how Marxist practice should manifest in the country. Regrettably, those staunchly following Stalin’s doctrines may have overlooked these subtle nuances.

Ray’s expressive style transformed the film into a series of stumbling blocks, disconnections and their continuations, powerfully infusing the audience with traditional beliefs about destiny and the contingencies of life. Vibhuti Bhushan’s novel was characterized by continuous and highly detailed narration. In contrast, Ray used a style of expression that is more suited to the art of cinematography, with lots of interruptions and a focus on specific events. In Pather Panchali, Ray brought to the camera only carefully selected high-energy moments from Apu’s childhood. The length of time between two moments is sometimes very long. Thus, time in film enters our experiences as a world-eater that surprises and sometimes terrifies us. This sense of time made the audience think not only about the characters, but also about their own existence. It was giving the audience an atmosphere that would make anyone philosophical. Pather Panchali’s realistic style of expression was a novelty in Indian cinema itself. Ray adopted Jean Renoir’s views that Indian cinema should be freed from Hollywood influences by focusing on India’s unique reality. Ray had inherited the ideas of neorealism from Renoir.

In “Pather Panchali,” the system was brought into question regarding Harihar’s family’s departure from the village. Conversely, in “Aparajito,” Apu faced accusations of negligence and ingratitude toward his mother, a stance seen as incompatible with Bengali tradition. Bijoya Ray, in her autobiography, highlighted her prior concern that Bengali audiences would not accept such a resolution. She noted Manik’s disappointment when theaters emptied after the first show despite an initial enthusiastic turnout. Ray’s portrayal did not adhere strictly to conventional mother-son love dynamics. It would be amiss to assert that Apu was indifferent to his mother’s well-being. After running away from home and working hard to buy a train ticket, when the train enters the station, Apu returns to his mother and tells her that he did not get the train. Apu’s aspiration for higher education stemmed from his endeavor to surmount the responsibilities imposed by maternal love and traditional expectations. He symbolized Indian youth transitioning away from orthodox traditions, eagerly embracing the values of modernity. Apu’s determination to pursue education in Calcutta, contrary to his mother’s wishes for him to embrace the traditional priesthood, exemplified this shift. Ray understood that even the life of an ordinary woman in Bengal—Sarbajaya’s lonely and desperate life towards the end, her anguished and painful demise—was a product of historical circumstances. Such distressing life moments are recurrent in historical contexts where traditional values are challenged and supplanted by new ones. Life’s poignant instances become most evident when translated into personal dilemmas. “Aparajito” faced skepticism from Bengali audiences, who perceived Apu as ungrateful to his mother, as relayed by Bijoya to Satyajit Ray. However, it went on to win the Grand Prize at the Venice Film Festival, surpassing Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood.”

At the cusp of the previous century, “Apur Sansar” vividly portrays the dire living circumstances faced by educated youth in Bengal, stifling their creativity and exacerbating unemployment. Despite this, his teacher encourages him to persist in writing. Evidently, loud slogans clamoring for change resonate outside. Subsequently, we witness Apu’s quest for employment while steadfastly continuing his writing endeavors. His modest earnings stem from teaching children privately, a meager ten rupees. Despite grappling with such hardships, Apu maintains a contented and optimistic outlook. Apu’s longtime friend Pulu pays him a visit, leading to an invitation to attend a wedding in Pulu’s village. The narrative takes a pivotal turn when the intended groom falls ill, compelling Apu to step into the role of the bridegroom for Pulu’s aunt’s daughter, offering solace to a divorced girl destined for a solitary existence. Following the wedding, Apu engages in a heartfelt conversation with the bride, expressing his concern about leading a modest life with his limited income, reflecting his anxieties rather than a display of pride over his actions. Apu’s character evolution is beautifully depicted, transitioning from the glorification of his own persona to embracing a break from tradition and advocating for modern education. Ray skillfully portrays the blossoming of an unconditional and profound love between Apu and Aparna, emphasizing their deep understanding and connection. In a tender moment, Apu confides in Aparna, articulating the profound significance of writing in his life. He poignantly expresses, “Do you know how dear writing is to me? You are dearer to me than that.” As the storyline progresses, Aparna becomes pregnant, leading to moments of separation where the affection between the couple is conveyed through heartfelt letters. Tragically, Aparna passes away after childbirth, highlighting the prevalent grim reality of pre-arranged marriages and the harrowing conditions women endured during that era. Despite Apu’s progressive and empathetic outlook, living in Calcutta, he remains ensnared by the prevailing dire social circumstances in Indian villages, marked by high infant mortality rates and maternal deaths, underscoring the need for societal change.

“Apur Sansar” was filmed in an inland village, and during the shoot, Ray was accompanied by his wife, Bijoya, and their five-year-old son. Upon completing the shoot, their son fell ill with a fever, and there was no medical assistance available in the village. In her autobiography, Bijoya vividly recalls the distressing situation and the desperate journey they undertook to travel for two and a half days by train to reach Calcutta with their ailing child. It was a harrowing experience, and Bijoya, summoning her strength, made the decision to leave for Calcutta while Ray was deeply distraught over their son’s condition. Vibhutibhushan writes the story of Apu in the early part of the last century. Not only then, but in the early decades of the last half of the last century, when Apur Sansar was filmed, and even now, proper healthcare systems are not functional in rural India. It was such social circumstances that determined Apu’s fate as his bride’s. Aparna’s departure devastates Apu, leading him to abandon the novel he was passionately writing, a heartbreaking manifestation of losing the person he cherished the most. The narrative underscores how adverse social conditions can stifle creativity and deter the aspirations of motivated and committed individuals. The poignant tale of “Apu’s World” culminates with Apu embracing the role of a father, symbolized by his reunion with his son and the journey to Calcutta, signifying hope and a new chapter in their lives.

Part 02 follows tomorrow

Click here to related articles.