In the smoke and static of 1970s Calcutta, Satyajit Ray turned the city into a crucible—where ambition, unrest, and fading ideals collided. His Calcutta Trilogy doesn’t just portray youth in crisis; it dissects a society on the brink. Job interviews become political trials, promotions demand moral erosion, and revolution simmers beneath every conversation.

With scalpel-sharp precision, Ray captures a generation trapped between rebellion and rot—where the real question isn’t what you want to become, but what you’re willing to lose. As connoisseurs of good cinema across the globe observed the maestro’s 104th birthday on May 2, writer, film aficionado and socio-cultural observer V Vijayakumar presents a three part series that studies Ray films from a unique perspective. This is the third and final part of the three part series.

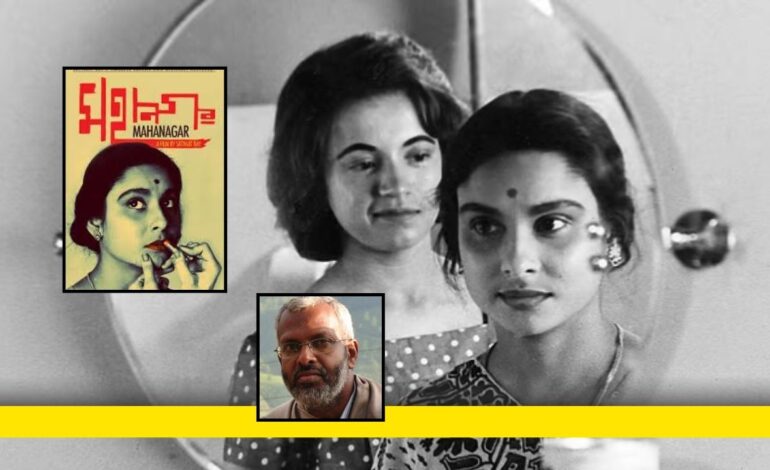

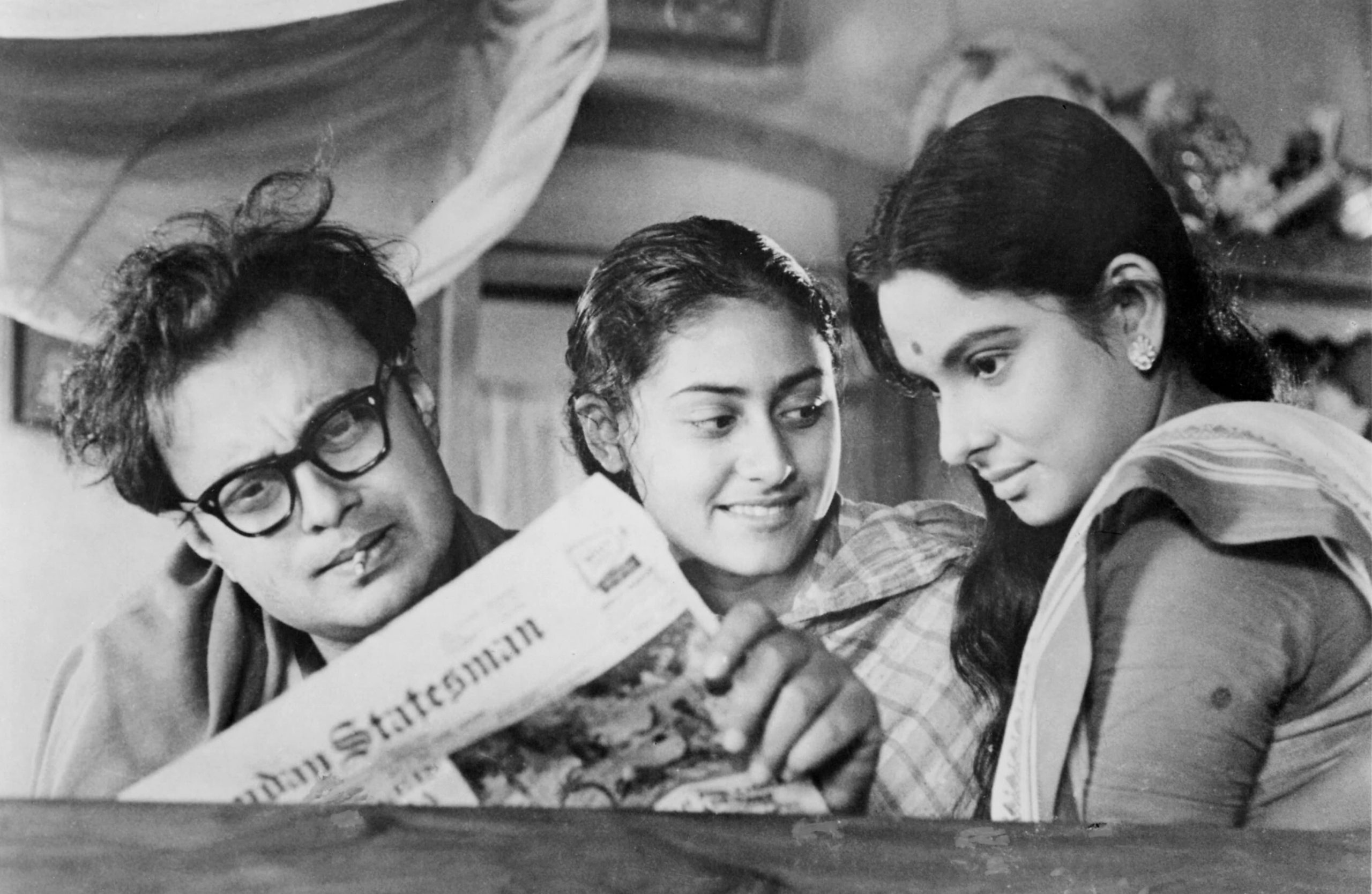

In Satyajit Ray’s “Mahanagar,” the city doesn’t occupy a prominent space. The film primarily showcases the offices where Aarti and Subroto work, with occasional views of the city from these settings. Ray’s exploration of the urban landscape becomes more pronounced in his films from the seventies. During this period, particularly in the turbulent seventies, Ray chose Calcutta as the backdrop for depicting urban life. The city grappled with the significant issue of unemployment of academics, a major concern affecting civic life. Additionally, the encroachment of capitalist development schemes was shaping new preferences and power dynamics. Traditional values of humanity and morality were being challenged by the emerging capitalist ethos centered on capital and profit. This turbulent thematic background set the stage for Ray’s Calcutta trilogy, consisting of “Janaaranya,” “Seemabaddha,” and “Pratidvandi.” These films revolved around the lives of the youth and carried implicit political statements within their narratives, offering a poignant exploration of the societal shifts and challenges during that era.

The film “Pratidwandi” vividly portrayed the life of the youth in Calcutta during the early 1970s, a time when the Naxalite movement was gaining momentum. Siddharth, the film’s protagonist, symbolized the disillusioned and protesting youth of that era. He embodied the political consciousness and commitment prevalent among the youth during that time. In one of the opening scenes of the film, Siddhartha is seen attending a job interview. An interviewer asks if you like flowers. Only with conditions, replies this young man. When questioned about the most significant event of the last decade, he answers unequivocally—the Vietnam War. This choice showcases Siddharth’s acute political awareness and underscores his belief in the importance of human struggles and resistance. In a pivotal moment, Siddharth’s reply regarding whether the moon landing or the Vietnamese struggle was more important serves as a powerful testament to his political consciousness. He distinguishes between the predictable triumph of technology (moon landing) and the remarkable resilience and bravery displayed by the Vietnamese people in their war for liberation. Hearing Siddhartha’s answer, the chairman leans back on his chair. The question arises from him whether you are a communist. Siddharth replies that it doesn’t have to be like that to honor the war of the people of Vietnam. Even long years after the release of Satyajit Ray’s film, this interview has entered the conversation of the youth. It points to the values that inspired the youth of that time. This scene resonated deeply with the youth, sparking conversations and highlighting the values that inspired and influenced the youth of that era.

Siddharth’s family is in the midst of complications. The film begins with the death of his father. He had to stop his medical studies. The sister, on the other hand, is obsessed with modeling and new costumes and lives subservient to the interests of the elders in the family. Her relationship with the office boss becomes unbearable to his wife and that lady breaks down in tears telling Siddharth’s mother about it. Siddharth’s younger brother is an activist of the Naxalite movement. Conversations about selling two books to study medicine and buying Che Guevara’s book suggest that Siddhartha also went through that movement. Broken clock symbolizes halted time in his life, its unfixable state reflecting his misery. Cinemas, brothels, coffee shops, pubs, streets, long journeys in the tram, love…the young life in Calcutta through Siddhartha’s life is narrated by Ray. Memories, dreams, and nightmares etched in the canvas of his existence. Childhood village sounds and chirping resurface in his recollections. Siddharth grapples with the allure of city life, drawn by friends who revel in its glory, making it hard to break away. Film’s climax: Siddharth arrives for another job interview. It culminates in a scene where he storms into the interview room and overturns the table and chairs in protest. Siddharth goes to a village after accepting a job as a medicine seller suggested by a leftist friend. There, while sitting in a lodge room, he hears the chirping of that bird in his memory. Mirroring leftist sympathizers like Mrinalsen, he adopts a profession akin to public service. Siddharth’s move to the village echoes his brother’s revolutionary departure from the city. Unconscious absorption of revolutionaries’ city-encircling from the village’s slogan manifests. The interview scenes and the film within the film, coupled with the newsreel showcasing Indira Gandhi’s subtle smiles and tax relief announcements for the affluent, distinctly hold political undertones. The backdrop includes the International Situation of the Vietnam War and the Paris Student Riots, while at the national level, the fading hopes of Nehruvian policies signal an impending economic crisis. The nation grapples with depreciation of the Indian currency and widespread agitation, foreshadowing the looming emergency. Satyajit Ray, once reticent about discussing his films, now openly engages in politically charged platforms, underscoring the urgency for artists to engage during pivotal times. He recognized the artist’s duty in critical junctures. Satyajit Ray, who infused politics at micro levels in Apu trilogy and Woman trilogy, speaks openly through Pratiwandi.

Sunithi Kumar Ghosh, a Bengal intellectual and politician, notably theorized the broker-like attributes of India’s big bourgeoisie. His book sparked significant discussions within the political realm. Ghosh contended that these brokers, acting as intermediaries, aligned their interests with the imperialist bourgeoisie. He argued that the wealthy class, prospering under colonialism’s patronage, embodied the negative facets of colonialism and capitalism, bearing the weight of imperialism. The mercantile essence of the upper class naturally permeated into the bureaucracy and the middle class. Satyajit Ray’s film “Jana Aranya”, portraying the betrayal and anguish of the middleman, echoed this narrative. The film’s protagonist is an educated individual, the son of an idealistic father, with strong convictions about values and politics. He secures a business deal by impressing his friend’s sister. Ray skillfully illustrates the gradual transformation of the honest and idealistic Somanath. Initially seen as compromises for survival, these actions later unveil capitalism driven by greed and apathy. All ideals become irrelevant under the magic of the social system that desecrates everything.

“Seemabaddha,” much like “Jana Aranya,” is a cinematic adaptation of Shankar’s novel, highlighting the tale of a young man ensnared in the snares of capitalist economic structures, ultimately losing his ideals. Shyamalendu’s aspirations for upward mobility within the corporate world lead him down a path of corruption and anti-people activities. His sister-in-law, who knew Shyamalendu from his educational days, is astounded by the transformation in his character. Tutul, who once admired Shyamal’s idealism and envied his marriage to her elder sister, now witnesses his orchestration of a fake strike by colluding with the labor officer at the factory to keep the company’s export contract extended. Workers get injured during the strike. The factory is temporarily closed. Through this fake strike, Shyamal saved not only the export contract but also his promotion to the post of director. Tutul, bearing witness to the erosion of Shyamalendu’s ideals, is his conscience. The film concludes with Tutul returning the watch he had given her and leaving. “Jana Aranya” and “Seemabaddha” present a clash between ideals and life’s harsh realities, showcasing how money taints everything, leading to the breakdown of human relationships. Tutul’s disillusionment signifies not only the collapse of an idealized image but also the deterioration of values that once nurtured a nation’s youth.

During the 1960s, Satyajit Ray faced criticism for not capturing the pressing socio-political issues the country was grappling with, as pointed out by notable critic Chidanandadas Gupta. Gupta emphasized the absence of depictions of burning trams in Calcutta, communal riots, refugees, unemployment, inflation, and food shortages in Ray’s films. Despite residing in the city, Ray seemed disconnected from the vengeful poetry prevalent in Bengali literature during that decade. Quoting left-wing critic Amitav Chattopadhyay, Monique Biswas highlighted the growing sentiment that Ray, once a revered humanist and the creator of masterpieces like “Aparajita” and “Pather Panchali,” was gradually becoming alienated from the people and their day-to-day struggles. This criticism seems to have been taken to heart by Ray, prompting a shift in his filmmaking approach with the creation of the Calcutta trilogy. The Calcutta trilogy represented a departure from Ray’s earlier works, specifically aiming to depict and interpret the tumultuous times the country was undergoing. Filming and showcasing the trilogy during times of crisis and upheaval allowed Ray to provide immediate interpretations, acknowledging the need to engage with current events. By immersing himself in these historical moments and intervening in their portrayal, Ray transformed from a mere observer to an active participant in the unfolding societal processes.

Click here to related articles.