Imagine a goddess in a gilded room—adored, worshipped, but trapped. Satyajit Ray’s lens lingers not on divine reverence, but on the quiet rebellion of women locked in roles they never chose. In the genteel corridors of Bengal’s Bhadralok households, Ray stages subtle uprisings, where solitude becomes political, and creativity defies control. This isn’t just cinema, it’s resistance wrapped in silence, a critique veiled in grace. Through Charulata, Mahanagar, and Debi, Ray observes. He listens. And in doing so, he rewrites the politics of femininity in a way few dared to imagine.

As connoisseurs of good cinema across the globe observed the maestro’s 104th birthday on May 2, writer, film aficionado and socio-cultural observer V Vijayakumar presents a three part series that studies Ray films from a unique perspective. This is the second part of the series.

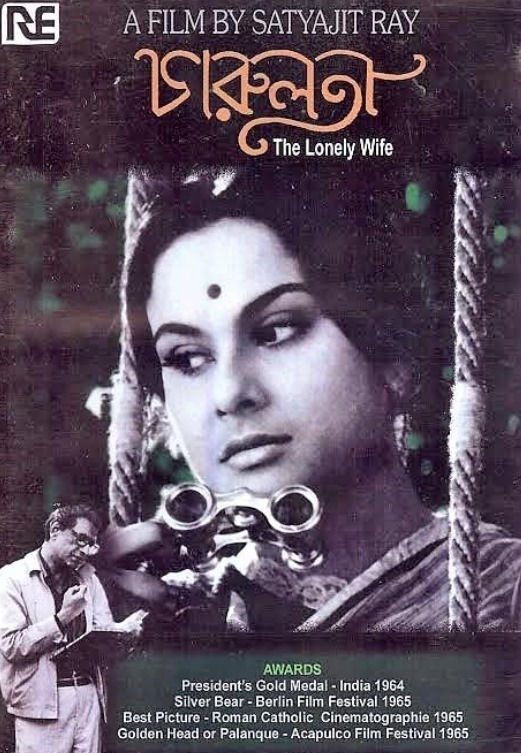

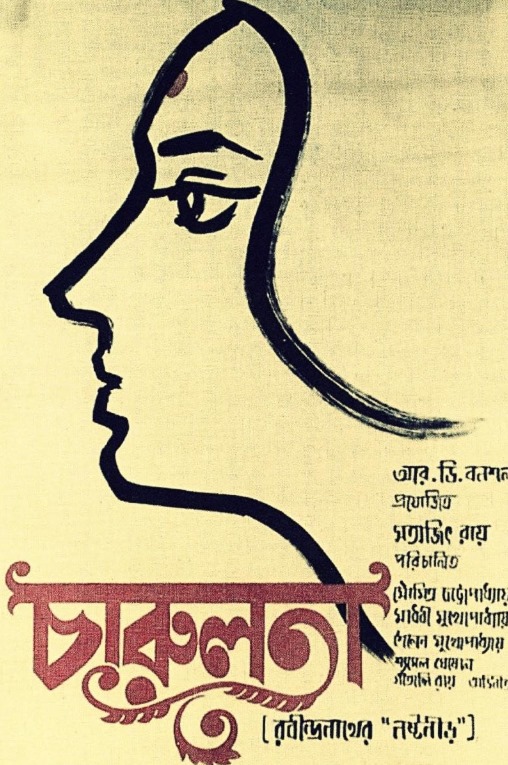

Ray’s female-centric trilogy delves into the lives of women within middle-class families, addressing pertinent issues that gained prominence in later times. Through these films, Ray narrates the stories of Bhadralok women in Bengal—individuals often revered like goddesses within the confines of their adoration rooms, yet grappling with complex inner lives. “Charulata” stands as a pinnacle achievement, acclaimed by Ray himself as one of his most astutely realized films. It was an adept film adaptation of Tagore’s renowned tale, “Nastanid” (The Broken Nest). Charulata, known widely at least beyond Bengal as Ray’s creation (not as Tagore’s creation), was brilliantly portrayed by the graceful actress Madhavi Mukherjee, embodying the content of the film. The name “Charulata” translates to “Charming Vine,” embodying a beautiful vine yearning to spread, analogous to the story of a woman aspiring to break free from the confines of being idolized as a goddess in the adoration room, to carve her own path. The film is situated in the late 19th century, a period akin to the time of Indulekha in Kerala, where the emerging consciousness of women like Indulekha mirrored a burgeoning sense of self-awareness. Indulekha boldly declared in front of Suri Namboodirippad, “I am” symbolizing the zeitgeist of the era when the intersection of Western education, Renaissance values and entrenched traditional beliefs stirred up a societal ferment across India. This clash of ideologies was particularly evident among the Bhadralok in Bengal, positioning them at the vanguard of this transformative period. Charulatha is Bhupathi’s companion who has acquired a sense of independence and political beliefs through western education. He runs a newspaper advocating for the rights of Indians. Bhupathi’s entire focus is on journalism and is passionate on Western liberal values. Just as Apu loves writing, Bhupathi loves journalism. Bhupathi tells Charu’s brother that my love for journalism is your sister’s rival.

In his palace house Charulata turns into a loner. The film begins with depictions of Charulata’s monotonous life. Remember the first scenes. Her monotony and weariness can be read in the graceful facial expressions, movements, body language and all the actions. Charu sometimes feels bored and disgusted even by activities she likes. She sews a handkerchief, shouts at the attendant, reads a book, and gazes outside through binoculars. Running from one window to another with a pair of binoculars, the heroine is freed from bondage and eager to know the outside world.

Meanwhile, Bhupathi comes out of the reading room, picks up a book and goes back to his office after reading it. He doesn’t see Charu standing in front of him. Bhupathi, who is engrossed in his reading even as he walks, pays no attention to her, even though he notices the elegance of his entire act. The director echoes the distance between them by showing Charulatha looking at Bhupathi through binoculars as he begins to fade from view. It is not out of love. We can be sure that they live in different mental worlds. We see Charu telling Bhupathi that she is very familiar with loneliness. Amal, Bhupathi’s maternal nephew, storms into Charu’s solitude. The director, who does not show the arrival of Charu’s brother and wife in the footage, depicts Amal coming in with the storm and heavy rain. Here, there is foreshadowing of the storm Amal will bring to the house. By showing the changes in nature, it points to the characters and the turning point of the story.

The heroine’s constant movements in the opening scenes of the film were a manifestation of her insatiable desires. Amal’s arrival accelerates these aspirations. Amal and Charu had a common world of interests to share. Charu is a good reader, a reader of Bankim Chandra Chattergee. Her reading reflects serious literary interests and the beauty of that mind. She is passionate about music. Charu couldn’t help but get close to writer-singer Amal. Ray uniquely captures their evolving relationship. See that garden scene that has been praised by all. The eleven minute long scene is full of romantic light. Sunlight, plants and trees, lawn, rhythmic swing, singing, poetry, writing, interesting gaze of Charu, pleasant conversations – in this environment the bond grows stronger unbeknownst to them. We feel Charu’s feelings for Amal growing every moment from the charms on her face. Amal becomes an inseparable part of Charu’s life, a blend of harmony and conflict, engaging in literary debates and occasional quarrels. Charulatha is exhausted when Bhupathi talks about Amal’s marriage and advises him to go abroad. She begs Amal not to leave the place. Meanwhile, Charu’s brother sneaks in with the newspaper’s money. Tested by his trickery, Bhupathi’s words about the loss of loyalty in human relationships were self-convincing to Amal of his ingratitude towards his brother. That night he leaves Bhupathi’s house without informing anyone. Bhupathi remains unaware of Charu’s emotional tie to Amal. Fatigued, he returns from a melancholic wandering. Charulata extends her hand to Bhupathi.

Satyajit Ray unveils Charulata’s feminine grace with poise. He locates the catalyst for change not in Bhupathi, an advocate of modernity, Indian interests and British criticism, but in Charulatha, secluded in opulent isolation within Bhupati’s palace. Ray emphasizes the significance of internal transformations in individuals, movements, and masses over superficial propaganda—a vital political insight. Ideas must resonate deeply inside the minds of people to effect change; otherwise, they falter. Political movements failing to grasp their own concepts or internalize them are destined to fail; a crucial political lesson often eludes those steering emancipatory endeavors. Conversely, reactionary forces sway minds by evoking emotions—a lamentable reality.

Bhupathi and Charulata’s differing tastes create a soul-searing divide. Bhupathi writes about politics. It is published for the public. Charulata writes privately, she wants it to be for private communications only. She urges to keep Amal’s garden-penned article private, refraining from publication. Beyond Bhupathi’s worlds of justice, beyond mechanistic prescriptive and ethical values, Charulata traveled in the world of creativity. It is in this world of creativity that Amal meets Charu. This is the content of Amal’s contrast with Bhupathi—he embraces creativity, guiding Charu. Bhupathi suggests Amal abandon poetry and writing, encouraging a move to England. However, Amal counters, highlighting the rhyming of “Mediterranean,” hinting at his poetic inclination. Humming lines from Bankim’s poetry, he conveys his desire to be a Bengali. The contrasts between Amal and Charu’s creativity and Bhupathi’s rational logic are at the heart of the film. Like Marx’s concept of dual missions of the British in India, Bhupathi’s duality emerges, valuing Charu’s creativity while asserting control over it. When he learns from his friends that Charulata’s article has been published, he feels both surprised and uneasy. At a time when it seems that Amal dares to talk about literature with Charulatha at Bhupathi’s instigation, Charu feigns a quarrel and withdraws, setting a nuanced tone. The director expertly crafts instances that underscore Bhupathi and Charulata’s distinct spheres.

Amal leaves Charu’s house under the conflict of ethical values. It must be said that the values of creativity fail. The film culminates with Bhupathi’s patriarchal ethos suggesting a tentative compromise to salvage the family, albeit with ambiguity. Bhupathi extends his hand towards Charu asking him to come inside the house, Charu extending his hand towards Bhupathi as if in response, the Director freezes the scene before their hands meet. Ray tries to keep the cage from collapsing. However, one may question whether Ray lost faith in the sanctity of family as an institution. This concluding scene echoes a longstanding endeavor to reconcile the conflict between tradition and modernity. Charulata and Bhupathi represent gendered spheres forged during the colonial era, navigating inevitable conflicts and tribulations. The internal struggles and efforts to find common ground, starting from Rajaram Mohan Roy’s dual focus on Vedanta and English education, persist beyond Tagore and even reach Satyajit Ray. Tagore’s narrative portrays Charulata’s refusal (‘No’) when Bhupathi invites her to accompany him. Could this signify Tagore’s desire for women to break free from confines and soar? Was the eminent poet articulating his wish for the collapse of the family rooted in masculine values?

We can find another answer. The story of Charulata was Tagore’s life story rather than a value distrust of the family based on masculine values. Bengalis believe that the story of ‘Nasatneed’ is an expression of the poet’s relationship with Kadambari Devi, wife of Rabindranath Tagore’s elder brother Jatindranath Tagore. Apart from this story, Tagore also wrote some poems about Goddess Kadambari. Kadambari Devi was a girl when she married the elder brother of the Great poet who was thirteen years older than Tagore. Rabindranath is only two years younger than Kadambari. Rabindranath and Kadambari grew up together. Kadambari was Tagore’s early companion in reading and writing. At the age of twenty-three, Tagore married Mrinalini. Four months after Tagore’s marriage, Kadambari Devi committed suicide. Later, in a letter to Amiya Chakraborty, the literary secretary, the poet talks about this suicide that emptied his universe. Andrew Robinson, who spoke to him about the matter, also writes that Ray believed that Kadambari was in Tagore’s mind when he wrote the story. The story of Charulata was also the story of Kadambari Devi. Thus, ‘no’ to Tagore’s Bhupathi by Charulata is symbolic of Kadambari’s disillusionment expressed through suicide. Charulata was life for Tagore and a story for us to read.

Ray’s film explores the possibility of intense love devoid of a physical dimension. While some viewers alleged a sexual undertone in Charulata’s obsession with Amal, sexuality isn’t a prominent theme in Ray’s major films. It’s suggested that Ray may have empathized with Madhavi Mukherjee, the actress who portrayed Charulata, akin to the feelings Tagore held for Kadambari. Bijoya Ray’s Bengali autobiographical notes shed light on the deep emotional connection between the great director and the blessed actress capturing an essence not fully translated in the later English version. Rituparno Ghosh’s film “Abohoman” seems to delve into the unseen aspects of this relationship, further exploring this complex emotional dynamic.

Ray’s “Mahanagaram” (“Great City”) is set in the backdrop of the 1950s, when the women of Bengal’s Bhadralok society moved away from being housewives and came out of the house for employment. This change, like all changes, brought conflicts. This is the story of Subrato and Aarati’s family. It is a family that follows the ideals of tradition, the ideal of a woman being a homemaker. There is a scene in the film where Subrato says to Aarati, the English phrase ‘A woman’s place is in the home’. Subrato’s casual reference to a friend’s wife’s profession triggers Aarati. She asks her husband if he agrees to go out and get a job. Subroto allows Aarati to take a job as a sewing machine saleswoman for a marketing company considering the household’s financial situation. This was a difficult thing for Subroto’s father and mother to accept. Aarati and the family grapple with conflicts between traditional values and the emerging modernity shaped by evolving social norms. Aarati adeptly navigates these transitions, symbolizing the fears, anxieties, and aspirations of women facing societal shifts. Ray empathetically captures this struggle, a feat uncommon among then male directors. Aarati, accustomed to covering her head with a sari before her husband, is now compelled to walk the city streets, sans a friend, and visit strangers’ homes for her job. She has to wear lipstick as part of her professional attire. But, freed from the domestic environment, Aarati becomes more energetic. She gains confidence. The head of the company praises her sincere dedication and efficiency in her work. Subrato becomes jealous of Aarati’s success and rise. He is shocked to learn that she is wearing lipstick. His concerns increase when he sees her walking down the city streets wearing cooling glasses over her eyes and interacting freely with men. Despite his internal struggle, Subrato allows Aarati to continue working, even as his own job loss exacerbates the household’s financial strain.

The film’s conclusion traverses through several problematic aspects. Aarati recognizes the unfair treatment Edith, her Anglo-Indian colleague, receives from the company head due to racial bias. He constantly says accusing words to her. Aarati asks him to apologize to Edith. Aartai’s demand shocked him. Naturally, he dismisses it with disdain. Aarti came in front of him ready to do an act that made him very nervous. Aarti goes out after giving him the resignation letter which he had to prepare earlier due to family pressure. The film ends with Aarati reuniting with Subrato, who consoles her under pressure and praises her sense of justice. They move in the hope that they can both find other jobs. Alternatively, it is an ending that can be quickly interpreted as a compromise with tradition and a return to old family values. A closer look reveals that this is not the case. It included the rejection of immoral and unjust interference maintained in the value system of the so-called modern along with liberation from the blind beliefs bound by tradition. The interpretation that the failures of modernity may lead to a return to the darkness of tradition is also not out of place. It is pointed out that as women start intervening in different discourses, the value system of men begins to shake and it falls into crisis. Ray says that women can bring femininity to any profession and that creates better relationships. Aarati’s ability to empathize with Edith is a sign of the pluralistic receptivity of the female world. Ray should have said that women could substitute the values of dialogue, equality, and pluralism for the authoritarianism and monotony of men, and that they stood closer to justice and virtue.

The film depicts humans facing the uncertainties of a changing world. The director creates many complex and ambiguous contexts for problematic situations. While Subrato is a good husband and father, he finds himself in a vicious circle when masculinity confronts his insecurities. Such moments of suspense have rarely been captured so compellingly in films. In one scene, Subrato is seen lifting Aarati’s sari to cover her head. In another scene, Edith writes lipstick on Aarti’s lips. There is also a scene where Edith gives Aarati a cooling glass. Aarati’s act of applying lipstick at Edith’s instigation had even shocked the female audience. The film drew large crowds of women in Bengal, a reflection of their aspirations and hopes resonating with Aarati’s character. The demand was so high that the film had uninterrupted screenings in Dhaka. Aarati became the focal point, capturing the audience’s admiration. The director meticulously crafted Aarati’s character, portraying her as loyal, honest, self-sacrificing, and emotionally profound. Madhavi Mukherjee’s exceptional acting skills elevated even the subtlest movements of Aarati, imbuing them with profound meaning. Through nuanced body language, she artfully portrayed the emotional turmoil of a woman leaving her child at home to work, the anxieties and shame associated with this decision in the eyes of her husband’s parents, and the pride of contributing to the family’s financial stability. Madhavi Mukherjee’s portrayal effectively conveyed the complexities and realities faced by women, resonating deeply with the audience.

If the depiction of Charulatha and Aarati being sentenced to life as goddesses in adoration rooms was metaphorical, then Satyajit Ray’s “Debi,” narrating the story of Dayamayi, can be seen as a literal portrayal of this lifelong detention. The theme of “Debi” revolves around Kalikinkar, a devout follower of Kali, who begins worshipping his daughter-in-law, Dayamayi, believing her to be an incarnation of Kali. This misconception leads to Dayamayi’s life taking a misguided course. Logical and educated Uma Prasad is unable to save Dayamayi from his father’s superstition. Dayamayi, who became a goddess, is touted to cure diseases and so on. Dayamayi herself doubts that she is a goddess. An attempt to sneak away to Calcutta with Umaprasad one night is abandoned due to her suspicions. Due to the conflict created by Kalikingar’s traditional beliefs and Uma Prasad’s modern logic, Dayamayi loses her balance, leading to mental and emotional breakdown, and ultimately untimely death. The film portrays how women, often devoid of authority in the realm of tradition or reason, become casualties in the power struggle between these forces. “Debi” faced objections from conservative elements, yet it doesn’t entirely align with reason; rather, it narrates the story of the early 19th century, shedding light on the consequences of rigid adherence to traditional beliefs. Kalikinkar, who transforms Dayamayi into the Goddess of Kali, is portrayed not as a villain, but as a victim ensnared by entrenched traditional convictions.

The men in “Charulata” and “Debi”; Bhupathi, Kalikinkar, and Umaprasad, are theoretically modern, yet they demonstrate a lack of awareness regarding the consequences of their actions. They represent a certain archetype of men, ostensibly modern but somewhat disconnected from understanding the implications of their behaviors and beliefs. This archetype is also reflected in the hero of the ‘Mahanagar’, illustrating that individuals confined to the male-centric world often struggle to grasp the realities until they undergo significant realizations. Satyajit Ray, much like his grandfather, was deeply concerned about women’s lives and had the ability to empathetically delve into their minds. He addressed this concern in his films long before the rise of political interventions that began recognizing women as a significant political category and acknowledging the distinct sphere. Ray understood that the complexities of women’s issues couldn’t be resolved through conventional reform activities alone. Ray’s films diverged from traditional themes that confined female characters to roles of motherhood, suffering, and service. However, it’s worth noting that Ray’s films predominantly featured Bhadralok women, underscoring the problematic aspect of the monotonous representation of women, showcasing a limited spectrum of female experiences.

Part 03 to follow.

Click here to related articles.