July 4th, Shamli, Uttar Pradesh: The Lynching That Wasn’t And Other Crucial Questions

The context: The results of the Lok Sabha Elections that came out on June 4, 2024 signified the return of the Narendra Modi led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)- National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government for a third term, albeit with the BJP not having a majority on its own. These results had instilled hopes, in a significant number of social and political observers as well as a section of political practitioners, that the sectarian and aggressive Hindutva agenda of the BJP as well as the larger Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) led Sangh Parivar, would get controlled since the saffron party was dependent on allies such as the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and Janata Dal (United) – JD (U) for majority in the Lok Sabha.

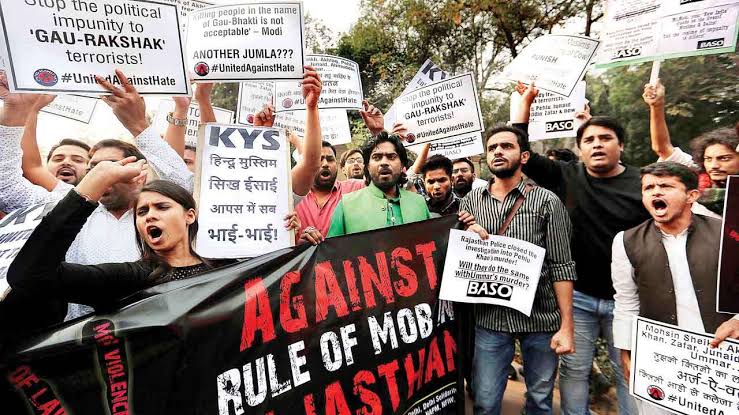

An important aspect of the BJP’s Hindutva agenda – of serial lynching, particularly of Muslims and in some cases of Dalits – that was reported from different parts of the country since 2014, the year in which Modi became Prime Minister for the first time, had also been referred to in the context of the 2024 Lok Sabha election results. This point was about the reported increase in lynchings after the year 2014. The media, civil society at large and several rights activists had pointed out that there was a correlation between the BJP led calls for the uniting of Hindus and the violence against Muslims. The hopes on the basis of the complexion of 2024 results was that the lynchings would not happen.

However, since June 4 as many as ten lynchings were reported from different parts India, including West Bengal, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh (UP). When lynchings first became a prominent part of the recent politics of hate, there were many conversations in the media on how to report on it. It is not always easy to differentiate a murder from a lynching. The Hindustan Times and then the news portal ‘India-Spend’ ran hate-trackers, both of which were shut down by 2019.

Since then, the conversations on how to tell the difference between a murder, a hate crime and a mob lynching have thinned. So this report seemed necessary, especially when our fact-finding revealed that one of the alleged cases, from UP, seemed not to be a lynching after all.

We, the people who keep a close eye on human rights excesses must also have conversations about how we tell our stories and when there may be an error in what we have seen. This story of a non-lynching would have been a non-story expect that it captured the political imagination. Therefore, it made sense to open it up forensically.

A fact-finding report by the Sarfaroshi Foundation, Shamli

There is a certain kind of fog and filthy air hovering over the district of Shamli in UP. It is a thick grease stain from 2013, when a local fight between Hindus of the Jat caste and Muslim Qureshis led to murder and then the worst communal violence Uttar Pradesh had seen in its recent history.

The twin districts of Shamli and Muzaffarnagar, where the violence played out, have been marked ever since as places where Hindus and Muslims have a new history of hate. The clashes that took place 11 years ago, resulted in over 90 people being killed and about 50,000, mostly Muslims, being displaced. It also led the BJP to drive a campaign across UP that Hindus are in danger and must unite against Muslims.

A decade later, UP, and Shamli in particular, is being seen as the place that is witnessing an interesting turnaround. From being the very epicentre of communal politics, promoted and steered by the Sangh Parivar, the State and Shamli are becoming the places where ruling BJP is becoming unstuck. In 2022, in the assembly elections, the BJP candidates lost all three seats. And in the general elections that concluded in June 2024, the candidate that won was a 27-year-old Muslim woman – Iqra Hasan on an opposition INDIA-Alliance ticket from the Samajwadi Party (SP). She ran a perfectly ordinary, non-communal election campaign which was her main victory and also that of the district, actively erasing its communal past.

As Iqra was sworn in to the 18th Lok Sabha or legislature, India’s new criminal code also became law – the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023. Many critics of the new law, such as the former additional solicitor general Indira Jaising pointed out that it gives draconian powers to an already centralised form of governance, advanced by the administrative and political leadership of the Modi government.

It is in this background that a Muslim man called Firoz was killed by being beaten repeatedly on the 4th of July, in a colony inhabited by Hindus from the Kashyap caste, in the village of Jalalabad in Shamli. A first information report (FIR) was filed by the police on this happening, naming three members of a Kashyap family.

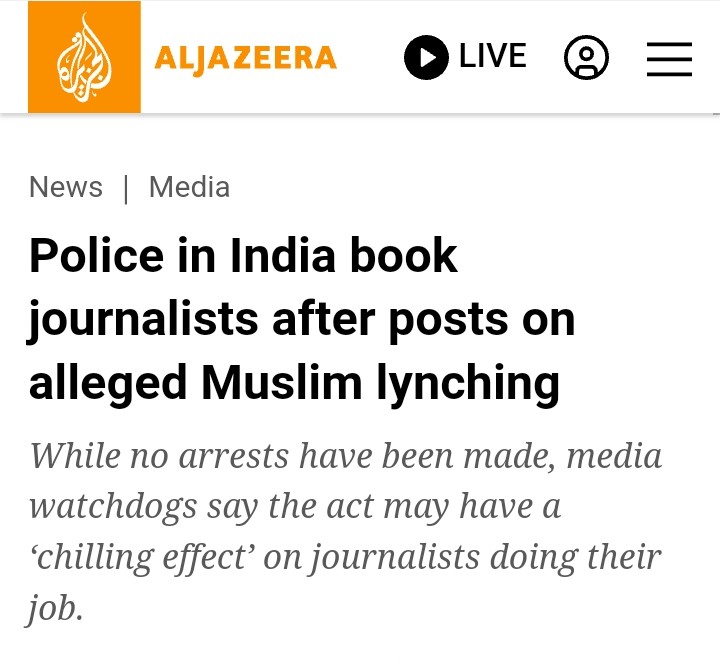

Two days later, on July 6, another FIR was filed by the police against five journalists who reported on Firoz’s death. The reports included a tweet on X, by Wasim Tyagi, saying this looked like a mob lynching.

In the atmosphere conditioned by communal polarisation on the one hand and the recent political reversals suffered by the BJP on the other, many stories were spun, principally circling around very sketchy information. It was being said that Firoz who traded in spare parts and discarded mobile phones had gone to the Arya Nagar colony at 8pm. The rest of his family was away attending a wedding. Firoz got into a scrap with three Hindu men from the Kashyap community. They killed him.

Some reports quoted one of Firoz’s brothers, saying he was killed because he sold his wares on a cart by playing out a pre-recorded message on a loud-speaker that offended Hindus. For this, it was being alleged, he was lynched. The plot-line was somewhat like this – Muslim man in polarised geography is synonymous with hate. Man plays his loudspeaker at a high volume. He is lynched.

As people who live and work in Shamli, and run a civil rights NGO called the Sarfaroshi Foundation, we felt we must cut through the clutter and find out what had in fact happened. My colleagues Ashvani Singh and Furkan Ali went to Jalalabad on the 9th of July. The first and most obvious thing they found was that Firoz was allegedly killed by three members of the same family, all of whom were mentioned by name in the FIR. That by definition is not a mob. Three people from one family killing one person suggested that Firoz perhaps knew them. Was this even a hate crime was the next question we needed to try and answer.

There were no obvious signs pointing in this direction. For one, Firoz never sold his wares at 8pm because nobody in Shamli does that, especially not street-cart vendors going from one gully to another in a village. Firoz’s brother Amjad confirmed that. If he wasn’t out selling, what was he in fact doing that late in the evening in Arya Nagar while the rest of his family was at a wedding?

Second, there seemed to be differing versions of the story from one of Firoz’s brothers to the other. One brother claimed that Firoz did drugs and the other vehemently denied this. One brother also claimed that some people in the gully Firoz visited and the family accused of killing him could possibly be dealers. We could not verify any of these claims because there was an eerie silence in the gully where the murder allegedly took place. No one wanted to say anything. But we were left wondering what Firoz went there for.

A sample of his viscera, being forensically tested should reveal in the postmortem report, whether in fact there were drugs in Firoz’s system, how his body had gone blue and why he was frothing at the mouth and near-dead when his brother found him. Especially since his family also told us he had a history of epilepsy and convulsions.

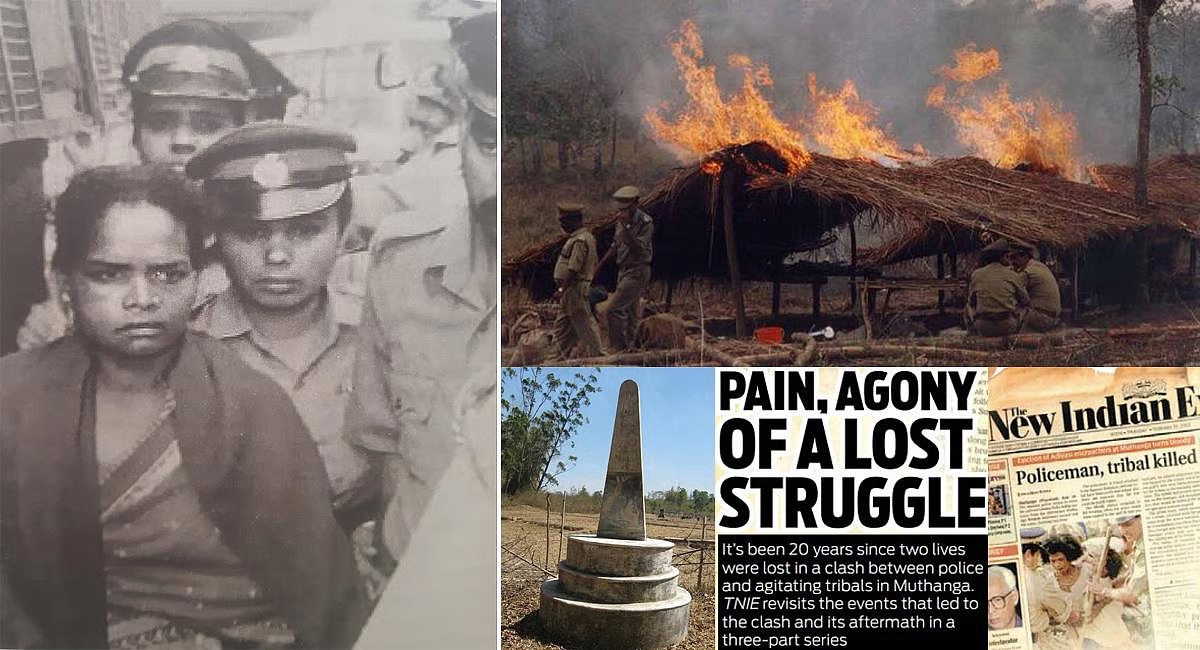

There also remain questions that an organisation such as ours have on the conduct of the police. How did the police end up filing a complaint against five journalists, under sections of the law that accuse them of promoting enmity between different groups (section 196) and making statements conducive to public mischief (section 353 b and c). If the police argues that there is nothing to suggest that Firoz was lynched by a mob, the same question must equally be asked of the police. What do they have on the reporters to suggest that they were deliberately promoting enmity or provocation? In this regard, we stand with collectives like DIGIPUB News India Foundation, the Press Club of India and the Indian Women’s Press Corps (IWPC) in condemning this action.

In the end, the story of Firoz is not about Firoz. It is about us and the stories we live with. If this was a murder, plain and simple, where should it be situated in the political and criminal landscape? Two weeks before Firoz’s murder, on the 21st of June, 2024, a Hindu man from the Kashyap caste, a man called Ram Niwas was killed by a group of six Muslim men from the Sheikh community.

When my colleagues Sahdev Goutam and Rajan Singh visited Ram Niwas’s family, in the village Khedi Gani in the neighbouring district of Muzaffarnagar, they said it felt like the mirror opposite of the Firoz story.

In the mirror: In Shamli, Firoz – a Muslim man from a dominant Qureshi caste is killed. Three members of one family from the Hindu Kashyap caste are accused, at the moment of culpable homicide, not amounting to murder. The Muslim family said they had trouble registering the case and had to rally around a large group, including political people to get an FIR.

Facing the mirror: In Muzaffarnagar, a few kilometres away, was the flip side of the story. A Hindu man from the Kashyap caste was killed by Muslim Sheikhs. The family here too, said they leaned on leaders from the Kashyap caste and then their complaint was filed.

In the arc of the mirror: Abutting Muzaffarnagar and Shamli, in the district of Saharanpur, a trained nurse, Seema, from the Dalit community of Chamars, was found dead and dumped on a cot outside the private clinic she worked in. Her sister said it took her and her father a day to get a complaint filed, after she elicited political support.

Members of the Hindu right wing Bajrang Dal and Dalit rights Bhim Army party clashed at the district headquarters over who was going to get the job done of having the FIR filed.

The context for Firoz’s murder, seems to us to be this. Placed not in a string of lynchings that have unfortunately taken place in this last month, but alongside these two other murders. In all three cases, people with little financial means and no political or social capital had to resort to whatever mode they could, to be heard.

Report filed by Ashvani Singh, Rajan Singh, Sahdev Goutam, Furkan Ali and Revati Laul of the Sarfaroshi Foundation.

Sarfaroshi Foundation is a human rights organization based in Uttar Pradesh, India, actively engaged in grassroots social and economic empowerment, with a special focus on building communal harmony.