From Cuba to India: Che Guevara’s Ideals in the Age of Democracy

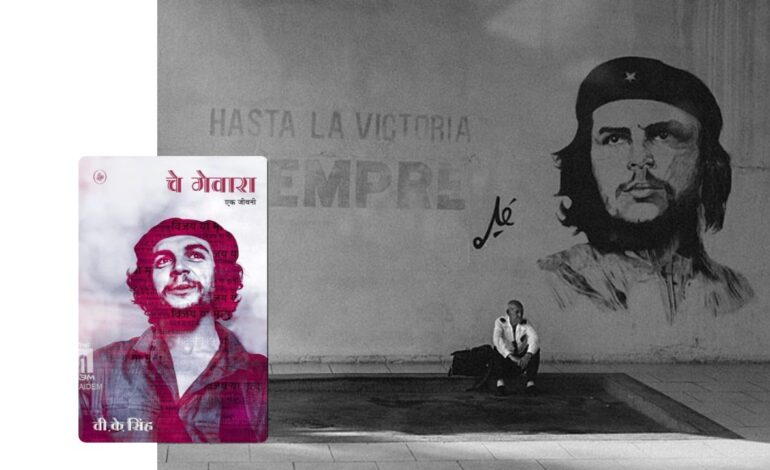

This discussion is a part of the ‘Book Baithak’ series, a collaboration between ‘The AIDEM’ and ‘Ka, The Art Café’, Varanasi, aimed at discussing books and authors relevant to contemporary India. In the latest episode of ‘Book Baithak’, author V.K Singh joined in to discuss his Hindi biography published by Rajkamal Prakashan, which focuses on the life and ideology of Che Guevara. This discussion delved deeply into Che’s early life, his profound humanitarian vision, and the relevance of his revolutionary ideals in the age of democracy.

The dialogue not only highlighted various facets of Che’s ideology but also shed light on the modern relevance of his perspectives in 21st-century democratic societies. Presented here is the written account of this session, offering a fresh perspective on history, politics, and contemporary issues.

Gaurav Tiwari: In the third segment of the ‘Book Baithak’ series, we are joined by Vinod Kumar Singh Ji to discuss his book ‘Che Guevara.’ Compared to the first two episodes, available on The AIDEM’s YouTube Channel, this episode is particularly fascinating for me.

The previous discussions were with professors, academics whose profession inherently involves writing books. However, today’s conversation with Vinod Kumar Singh Ji is very different and uniquely inspiring. He worked for LIC, and after his retirement, he began writing books.

For readers like me, who enjoy reading books as a hobby, this discussion is both intriguing and motivating, as Vinod Ji’s journey transitioned from a passion for books to becoming a full-time author.

So, Sir, how did this transformation from being an LIC employee to becoming a full-time author happen?

V.K Singh: I joined LIC in 1972, and soon after joining LIC, I was introduced to trade unions. Alongside initiating trade union activities, I developed an interest in leftist movements, which naturally led to the process of struggle. Fortunately, the trade union I was associated with was recognized as one of the most dedicated unions in India.

It had a rich tradition, and let me add that the Life Insurance Corporation of India, which is a public sector institution, was established in 1956, where the India Insurance Association played a pivotal role. I was connected with that very association. It was from there that my journey and transition began. Gradually, my interest in reading and writing started to grow.

From then on, I became acquainted with the ideologies of figures like Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, and Ho Chi Minh. Writing for magazines, documenting the history of trade union movements, and similar activities continued simultaneously. When I retired, I decided it was time to repay the debt I owed to society.

At the age of 75, repaying this debt to society was the only way I knew—something I had been acquainted with for the last 50 years. Even while working, I retained my hobby of writing, which continued without interruption.

Gaurav Tiwari: As a full-time author, what differences did you find when publishing a book compared to writing while working a job? What challenges come with being a full-time author, and how is it different for those who write and read while managing a job?

V.K Singh: You see, my experience of writing while working a job was quite different. I don’t have direct experience as a full-time author, so it’s difficult to comment on that. However, I believe that wherever we are, we should perform our duties with complete honesty as workers and laborers.

While working, I was fully involved in movements alongside handling my official work. I take pride in having worked with integrity throughout my life. That’s why, while being deeply engaged in my work, I didn’t have the capacity to open a ‘fourth chapter’ of my life for writing. When I finally got time, I began writing.

In this journey, my interest in Che Guevara began to take shape. I read Gabriel García Márquez’s dialogues with Fidel Castro, Fidel’s voluminous books, and other related materials. Once, during discussions on these topics, someone suggested translating them into Hindi. As I started translating, I realized that instead of mere translation, I needed to present these extraordinary personalities—Fidel, Che, and Ho Chi Minh—in my own way for Hindi readers.

These three individuals are deeply interconnected. You can’t truly understand Fidel Castro and Che Guevara separately. This is where my interest in Che Guevara grew and the process of writing about him truly began.

Gaurav Tiwari: What inspiration and lessons can today’s youth take from Che Guevara? What can be learned from his early life, especially his time as a student, and what inspiration can be drawn from his later life?

V.K Singh: To understand this, one must first reflect on what Che Guevara represents to you. Do you see him as a symbol of guns and violence, or do you perceive him as a symbol of humanity and humaneness—someone who envisioned transforming a society of individuals taking lives into a society of individuals cherishing each other’s lives? Che Guevara was not someone who took lives; he is regarded as someone who was ready to sacrifice his own life.

When you view him from this perspective, only then will you grasp why it is important to know and understand Che Guevara. He never advocated for revolution through guns or violence alone. Whether it was Bolivia, Congo, or Cuba, whenever he was involved in a revolution, he spoke of people’s uprisings. He led by example, inspiring people to join the cause.

Today’s youth must realize that Che Guevara was an ordinary child, just like any one of us. To become Che Guevara, one does not need to be superhuman. History has repeatedly shown us that extraordinary accomplishments are carried out by ordinary people. The power and capacity to achieve the extraordinary rest only with ordinary individuals—common people, the masses.

This is where the youth must draw inspiration from Che Guevara and reflect on how they relate to his thoughts and personality. His ideology finds its roots in this very understanding.

Gaurav Tiwari: Che Guevara was born into an upper-middle-class family in Argentina. By training, he was an MBBS student, but at a young age, he participated in the anti-colonial struggles in Cuba and Bolivia. He stood alongside the local people in their fight against colonialism, even though he was not a citizen of those countries.

Did Che Guevara’s life have experiences that instilled in him the empathy to understand and connect with the struggles of citizens from other countries? What in his life inspired him to transcend his upbringing and the environment of Argentina to stand against injustice?

V.K Singh: Che Guevara’s family belonged to the feudal middle class, but it was a feudal middle class that was on the brink of collapse. The complexities of that background were with him. However, during his studies, especially when his journey began with ‘Motorcycle Diaries,’ it wasn’t driven by any specific objective. He didn’t set out thinking that he wanted to lead a revolution or achieve something grand.

During the journey, his experiences began to influence him. It was here that the process of detachment from his familial background started. When he stepped out into the world, immersed himself among the people, and encountered their struggles, his perspective started to change. He visited entire colonies of leprosy patients, lived with them, and began to understand the reality of their problems.

The center of his revolutionary transformation was Mexico. At that time, Mexico was the hub of revolutionary movements across Latin America and South America. Young individuals fighting against tyrannical regimes gathered there. It was in Mexico that Che Guevara’s perspective began to mature.

There, he engaged in dialogues with Fidel Castro. As he became more closely associated with Fidel, their thoughts became inseparable. At first, he joined the revolution as a physician, but soon he had to make a decision—whether to pick up the gun or the medical kit. It wasn’t practical to carry both, and survival demanded a choice.

Che Guevara decided to abandon his profession as a doctor and embrace the role of a revolutionary soldier. The Cuban revolution was a testament to the strength of ordinary people. No outsider overturned the regime there. The farmers of Cuba formed their army, and the revolution was carried out using weapons seized from the armies of the tyrant Batista.

Che Guevara’s decision exemplifies that ordinary individuals are capable of extraordinary achievements. The Cuban revolution proved that the essence of a revolution lies with the common people. This was where Che Guevara’s journey of dedicating himself to the cause of revolution truly began.

Gaurav Tiwari: When reading Che Guevara’s biography, three aspects of his early life particularly stand out. First, he was deeply passionate about reading. He read books on every subject, even though he later pursued medical studies. He even created his own dictionary, where he documented all philosophical terms. He read works by philosophers from India and around the world and included ideas from the European Renaissance and Indian Oriental philosophy in his dictionary.

Second, he had a profound love for traveling. In a previous discussion, Prasadanand Shahi pointed out how, in India, the tradition of reasoning among Bhakti poets was derived from their experiences and travels, with traces of Buddha’s influence evident. Similarly, Che Guevara also traveled extensively during his school and college years. He documented these experiences in his book ‘Motorcycle Diaries,’ which captured the essence of his journeys.

Third, and what I find most inspiring about his youth, is the empathy he developed to understand the problems of others. Even during his studies, he was actively volunteering. As you’ve mentioned, he also volunteered for leprosy patients.

V.K Singh: During his studies, it became evident that Che Guevara had a deep desire to understand and learn about things. His curiosity and thirst for knowledge came naturally. When you’re in school, books serve as the primary source of information. For this reason, he immersed himself completely in reading books.

He made efforts to learn and understand every subject. That’s why I described him as ‘multifaceted,’ because he wanted to understand and explore the entire world. He sought to comprehend not only its essence but also its philosophy and behavior. For him, combining the philosophical and practical aspects of life was essential.

When he had the opportunity, books became a major part of his passion. His love for books didn’t remain confined to reading alone. Later, as he embarked on motorcycle journeys, his passion for exploring the world grew. And when the zeal for revolution ignited, he embraced it wholeheartedly.

Gaurav Tiwari: Now that more than 50 years have passed since these events and you wrote Che Guevara’s biography after 2010, which revolves around events of the 1950s and 1960s, what did you feel while writing? Could Che Guevara have done anything differently? Were there aspects of his methods or lifestyle that he should have reconsidered or changed?

V.K Singh: It wasn’t up to Che Guevara to decide what he could or should do—it depended entirely on the socio-political circumstances of that era. When you look at the history of the 20th century, at that time, solutions to most problems were being sought through the use of weapons. If you’re confronted by a barrage of bullets, trying to offer a rose is simply not feasible.

You have to choose your weapons, strategies, and tactics according to the time and circumstances. In this context, there wasn’t much room for change. However, it would be absolutely wrong to claim that Che Guevara—or any revolutionary, for that matter—sought to change the world solely through violence. Picking up arms was a necessity forced by the conditions of the time.

This is why the arsenal of revolution included not just guns, but also violins and roses. Revolutionaries had to determine, based on the circumstances, when to wield a gun, when to use a pen, when to play a violin, and when to present a rose. The 20th century was an era of weapons, and at that time, there was no alternative to taking up arms.

The real revolution begins afterward. Alongside political revolution comes the work of ideological revolution—when the process of winning over the masses begins. Guns alone cannot win over such a large population. You have to bring people to your side with love and ideological engagement.

The destructive phase ends, and the constructive phase begins. Change then starts with love and empathy. That is the essence of true revolution—a revolution that conveys the message of love and creation to humanity and the masses. This entire process of transformation begins from here.

Gaurav Tiwari: “How was a balance established between revolutionary zeal and the principles of non-violence and peace? Is it possible to harmonize these two ideologies?”

V.K Singh: “Striking this balance is essential, and it remains equally relevant today. You see, reconciling revolutionary fervor with change has always been a challenge. Even now, if you examine our society, the circumstances have not entirely changed.

For instance, consider how many people are still imprisoned under UAPA (Unlawful Activities Prevention Act) in our jails. Who are the individuals being lynched in mob violence? When Graham Staines was burned alive, the question arises—who were the ones who set him on fire? Violence has still not been entirely eradicated from our society.

However, today’s context is different from the compulsions of the 20th century. You cannot simply pick up a gun and march into a revolution anymore. First, the conditions are no longer the same, and second, the disparity created by power and technology has significantly widened. There was a time when you could seize weapons from rulers to carry out a revolution, but today, the ‘Military-Industrial Complex’ has altered that equation.

Take the pandemic for example. During COVID, the entire world was shut down for a year. Despite this, the capitalist class managed to multiply its wealth several times over. In such a scenario, relying on mass movements becomes the most viable option.

Eventually, even endurance has its limits. For change, you must take to the streets, but it is clear that in today’s time, direct armed conflict will not achieve change. For example, in Mexico’s Batista movement, Sub-commandent Marcos explicitly stated that they were not there to stage a revolution or rewrite the history of the world. He made it clear: “We cannot write your history for you, but we can say this much—your history must be written by you, and you alone.”

This is the essence—change and revolution must come from the people and be for the people.

Watch the full interview with VK Singh from the Book Baithak Series here.