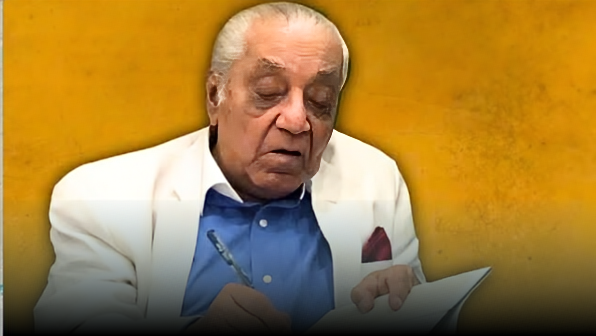

Abdul Ghafoor Majeed Noorani (September 16, 1930 – August 29, 2024)

Abdul Ghafoor Majeed Noorani (September 16, 1930 – August 29, 2024)

It was when I was a trainee sub-editor at the Indian Express office in Bangalore that I saw for the first time Abdul Ghafoor Noorani, a regular edit-page columnist in the newspaper when it was under the ‘rule’ of the iconic Ramnath Goenka, Arun Shourie, the national editor and T.J.S. who was the Resident Editor of its Bangalore branch. His stature was too intimidating for me to go near him, let alone speak to him. That was in the mid-1980s. Little did I realise then that he would become a much-read, much-appreciated and equally much-reviled columnist of Frontline, which was barely a year old then, and I would be speaking to him every fortnight for about two decades first as the Associate Editor in charge of the magazine and later as its Editor.

The second time I saw him and had, by then, acquired the confidence to speak to him was in the late 1990s. On a humid afternoon, Noorani walked into the Frontline office to meet the News Editor. As the News Editor was away on leave he spoke to me. Just before he left the office he asked me to suggest a good non-vegetarian restaurant in the city.

Immediately, the name Karaikudi came to my mind. It was popular then for its specialisation in Chettinad cuisine. He thanked me and left.

A month or so later, there was a phone call and I had to attend it.

It was Noorani with his stentorian voice on the line. He wanted to know who he was speaking to. As I mentioned my name, he said immediately, “So, you were the gentleman who suggested the excellent restaurant in Chennai. Thank you. You know I took ‘parcels’ worth thousand rupees back to Mumbai! Thank you once again!’

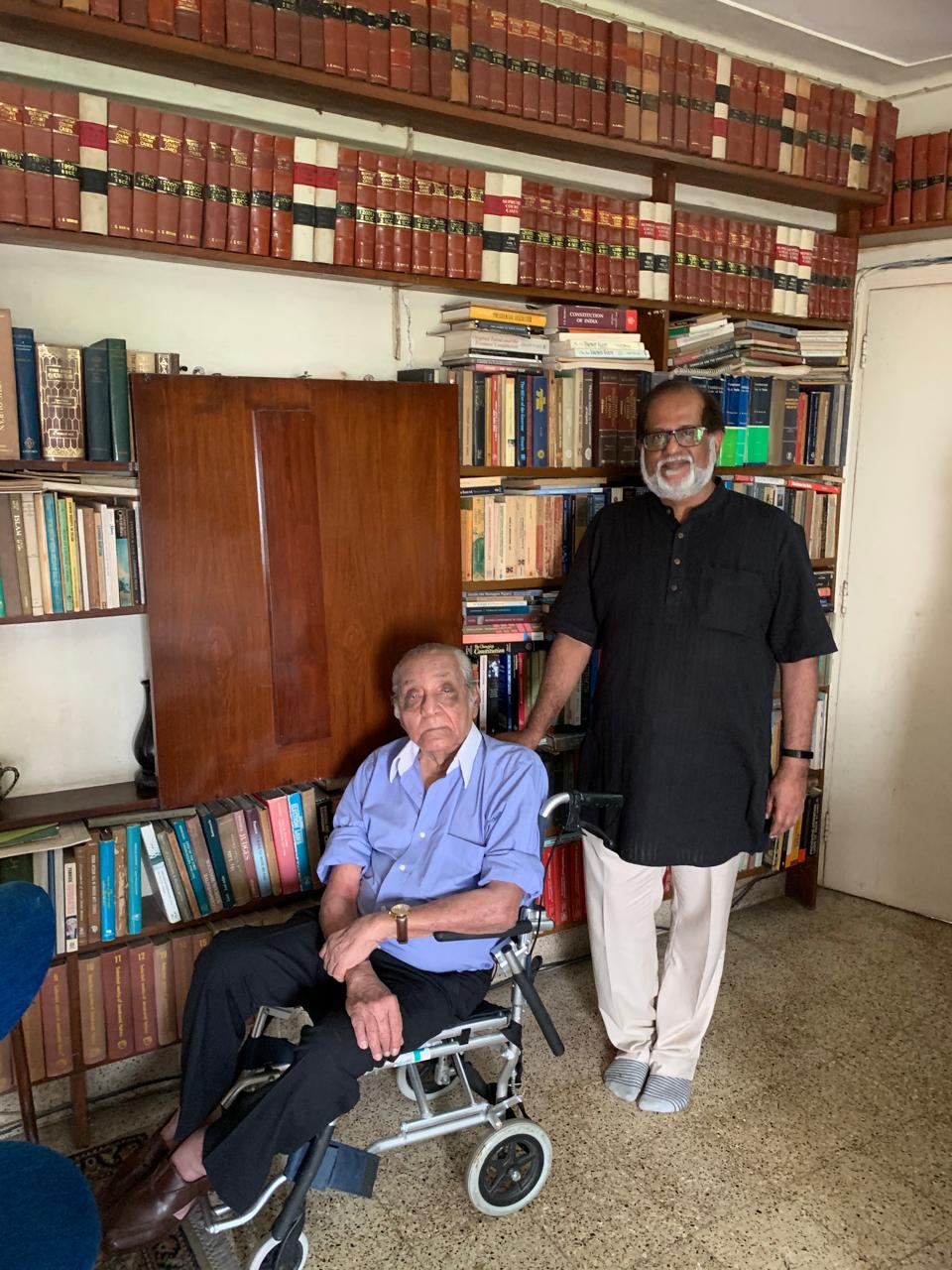

That was the unlikely beginning of a long association between a scholar, thinker, writer extraordinaire and a senior editor of a serious socio-political magazine. That association, which was predominantly professional, occasionally strayed into to the personal when the undying foodie in him sought my advice on where to eat and what to eat when he visited other Indian cities than his much-beloved Mumbai, or when he shared flattering and not-so-flattering anecdotes involving some of the big names in politics, government, journalism and the world of diplomats. The professional association came to an end about four months before my retirement as he wanted to complete his book on the Demolition of the Babri Masjid, which, incidentally, he wanted to dedicate to Frontline. By then he was wheelchair-bound and had to be dependent on a personal assistant. His contribution to Frontline became few and far between. The personal association came to an end yesterday (August 29) when he passed away at the age of 93 in Mumbai.

I had the rare privilege of speaking to him every fortnight a few days after the issue had been uploaded for printing at a press in Hyderabad. He’d call me around mid-week on my direct landline (only landline until he unwillingly acquired a mobile phone in the late 2010s) and discuss with me his article idea not just for the subsequent two or three issues of Frontline. Such was his dedication and discipline that he would mark his schedule in his table calendar. And for every article he proposed he would ask me for permission. Little embarrassed, I’d say, “You have a blank cheque. There are readers who subscribe to Frontline just to read your articles. You need not ask for my permission.” He’d reply: “No, my friend. You are the Editor and I have to get your approval every time I write for you!”

The first ever article he wrote for Frontline was in the issue dated April 28-May 11 and the headline was ‘Taming the RAW’. It gave an idea of the shape of things to come from him. They did come unfailingly for three decades. A back of the envelope estimate done by my former colleagues at The Hindu Archives shows that he might have written about 500-odd articles. There have been about 1000 entries in the name of A.G Noorani, which include citations, footnotes, letters to the editor, and so on.

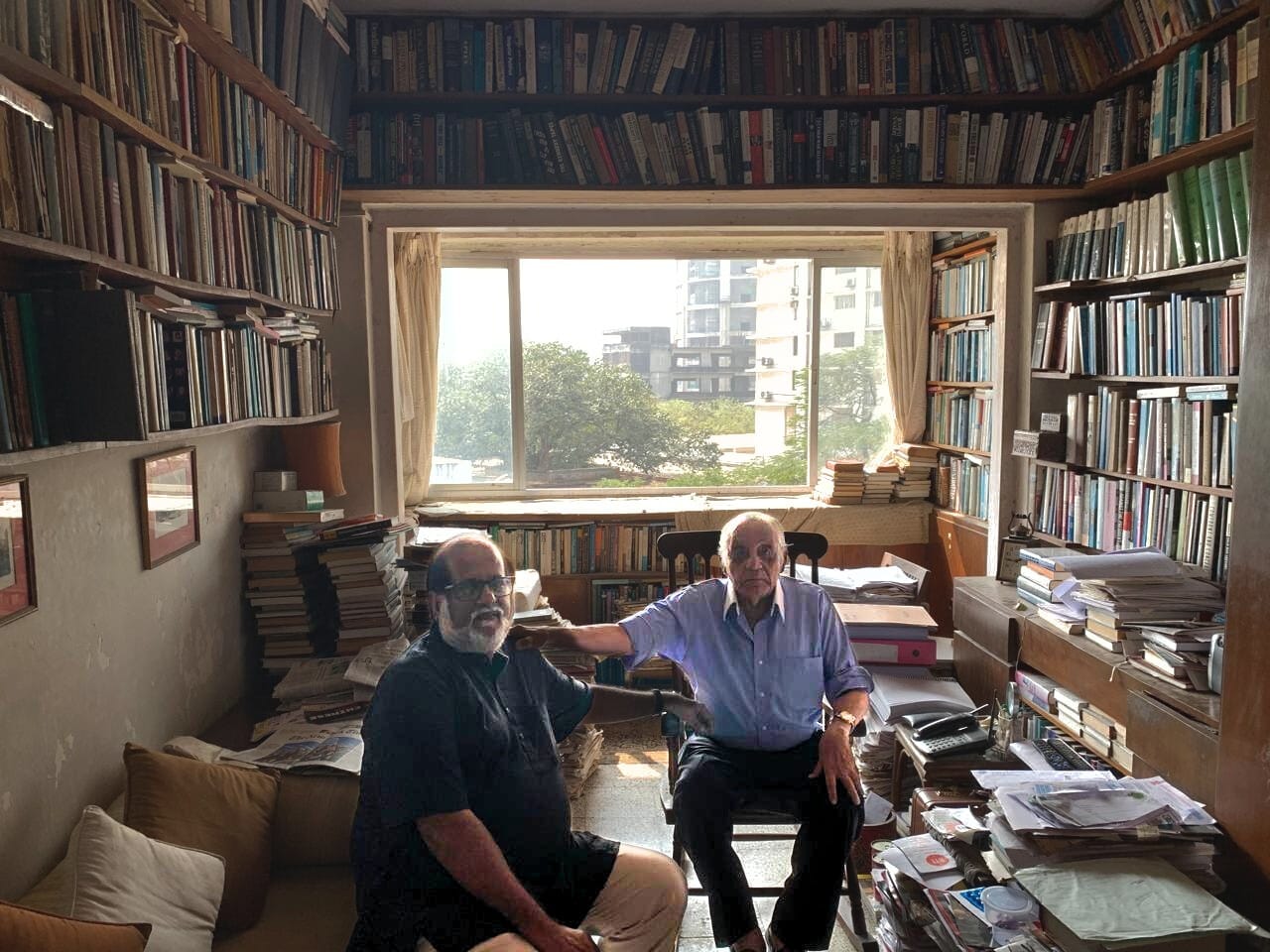

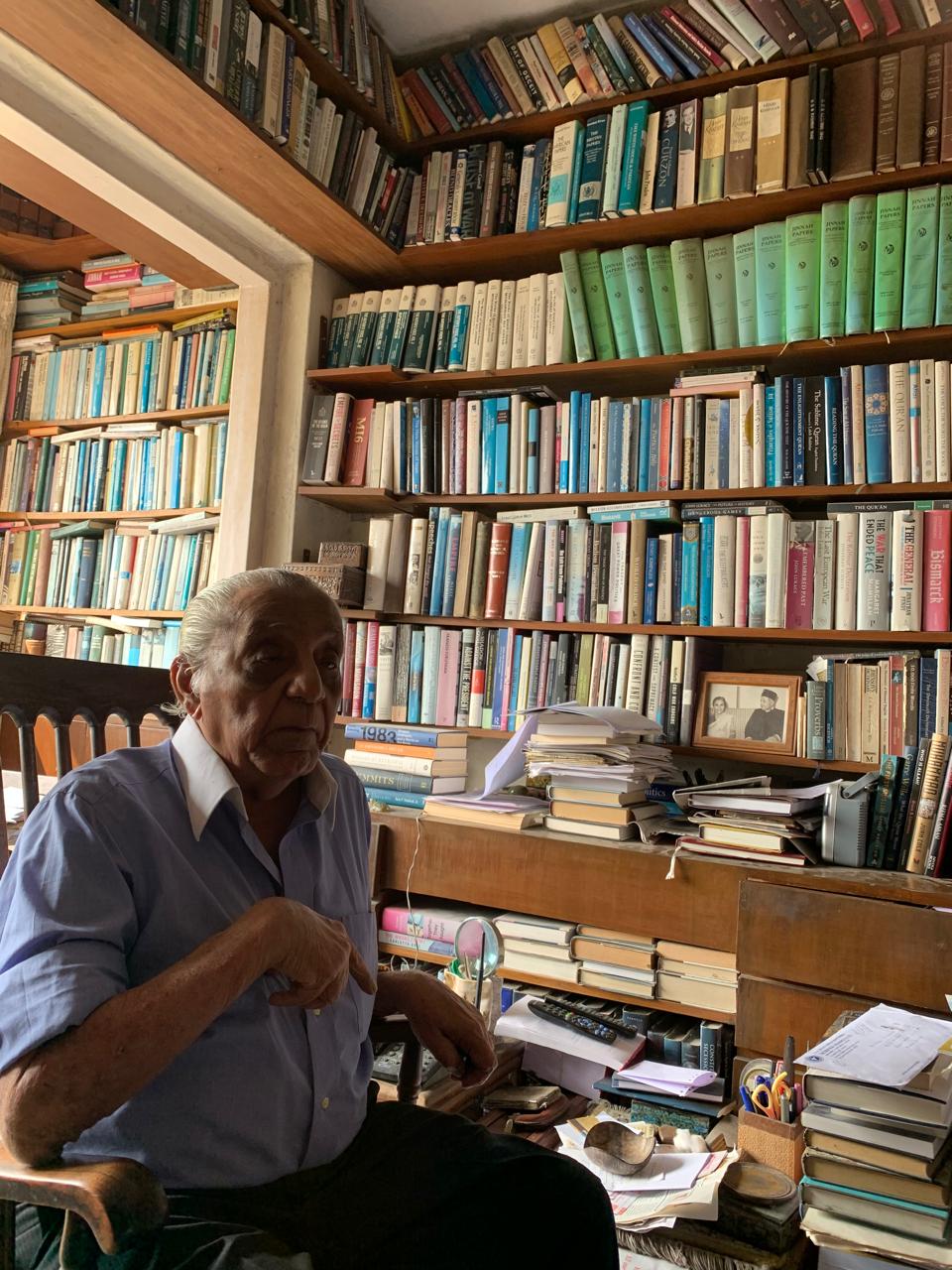

And his last contribution to the magazine was in the issue dated September 9, 2022 with the headline ‘Judges and their bogus collegium’. It was written at the ripe age of 92 – an indication that despite his troubling physical inconveniences his intellect remained untamed and never flinched from speaking truth to power. It may not be an exaggeration to say that it must be a world record for a writer to write continuously, profusely and courageously on subjects ranging from Indias struggle for freedom, the decline and fall of the Congress and the rise of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-backed Bharatiya Janata Party, India’s troubled relations with its neighbours such as China, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, searing critiques of controversial verdicts from the judiciary, Jammu & Kashmir, the constitutional history of not only India but the big powers, human rights… the list is too long to be exhausted in an article. And each of these articles was based on rock-solid historical, legal, legislative and literary sources, the collected works of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose, Vallabhbhai Patel and painstaking research at the prominent libraries of India. A crucial, unassailable source was his personal archives of newspaper clippings dating back to the 1950s. An interesting anecdote he narrated in this connection was the visit of intelligence officials to his two-room apartment in Mumbai enquiring him about a piece of information which until then was considered in official circles as ‘classified’. Noorani pulled out a file and showed the newspaper clipping carrying that piece of ‘classified’ information. His humble residence would pass for a mini library. Even the kitchen was stacked with books. He lived among books.

My fortnightly conversations relating out anecdotes relating to his encounters with politicians, bureaucrats, diplomats and journalists, passages from books and articles, laws and constitutional provisions, slices of contemporary history, and so on, were as enlightening as his articles and books. After witnessing a political conclave of opposition parties in Lucknow he said this about DMK president and former Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi: “None can beat him in repartee.” On being introduced to former Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalithaa by a political leader, he said, “I am Noorani.” Pat came her reply: “I know you Sir. I regularly read your column in Frontline.”

Dealing with an old-timer like him was professionally challenging and cumbersome exercise. His routine was to write down his articles running to about 3000-4000 words, send them to a stenographer, read the typed sheets and make corrections, send the corrected version to the Mumbai office of The Hindu for it to be faxed to the Chennai office of Frontline. The original article would then be put in an ‘office packet’ and despatched to the Chennai office. As soon as we received the faxed article, we would send it for typesetting. The next task of the Frontline desk was to read the typeset article along with the original and make corrections, if any. All this, about two decades after newspaper offices transitioned to computers and online editing. Typewriters were part of history but Noorani, the man who made history in a way, wouldn’t ask his stenographer to give up those machines of old world charm. Mr. N. Ram, the Editor-in-Chief of The Hindu Group of Publications, offered to gift a computer to his long-time friend ‘Ghafoor’ (the name Noorani preferred) so that we at Frontline could cut short the production time. Noorani would have none of it. Though his stenographer shifted to computer in the middle of 2011, Noorani would not give up his pen and paper. However, all the tedium of getting his articles published would vanish once you start reading his erudite, stinging, occasionally acerbic, intellectually stimulating article’s proof.

If and when I called him to get a clarification about a characteristically powerful sentence or two, he would give three or four equally powerful alternatives. Another notable attribute of his writing was that he would not be content with just citing a newspaper article; he would cite it with the byline of the correspondent or writer concerned. This was contrary to the general media practice of not giving due credit to a ‘rival’ newspaper or its correspondents.

Apart from the enviable collections of books, documents, and newspaper cuttings, what struck me when I visited his residence was the humble 2 feet-high-cot sitting on which he wrote articles that kept long-form journalism alive and voluminous books that made politicians, policymakers and diplomats sit up and listen to him.

It was not as if Noorani only spoke truth to power and the powers-that-be received his wisdom passively. He was an important name in what is known in officialese as Track II diplomacy. He was not just an intrepid critique of foreign policy who did not offer insightful ideas for regional peace achieved through negotiations.

In this connection, A.S. Panneerselvan, former Executive Director, Panos South Asia says:

“Panos South Asia, in association with Himal Southasian, has held nine India-Pakistan ‘gatekeepers’ retreat’ since May 2002, when the first get-together was organised near Kathmandu. These retreats, which bring together senior journalists and experts with in-depth knowledge of the bilateral processes, spring from the faith that in a world of changing equations and moods, rapprochement between New Delhi and Islamabad is a key factor for a safe and prosperous South Asia.

“We invited some prominent editors and owners of media houses from both of the countries for an open, informal and informed sharing of experiences and information.While we had diplomats and domain experts to provide both context and the potential way forward, the most erudite contribution for the mutual dialogue came from A.G Noorani when he spoke about the composite dialogue between India and Pakistan at a retreat held in Bentota, Sri Lanka, September 2004. Noorani located the bi-lateral relationship between the two countries on a larger register that was inclusive of the following themes:

- Internal factors in India influencing relations with Pakistan, including issues related to political equations, vote banks, radical groups, popular will, and militancy.

- Internal factors in Pakistan influencing relations with India, including the role of the military, radical groups, political factors, popular will and militancy.

- External influences on bilateral relations vis-à-vis Pakistan, including the ‘US factor’, the West’s positioning and the Islamic world, energy needs and the role of China.

- External influences on bilateral relations vis-à-vis India, including the ‘US factor’, energy needs and the role of China.

Noorani’s plea exemplified the need for a permanent place for reasoned debate and mature deliberation in the India-Pakistan dialogue for enduring peace and development of the region.”

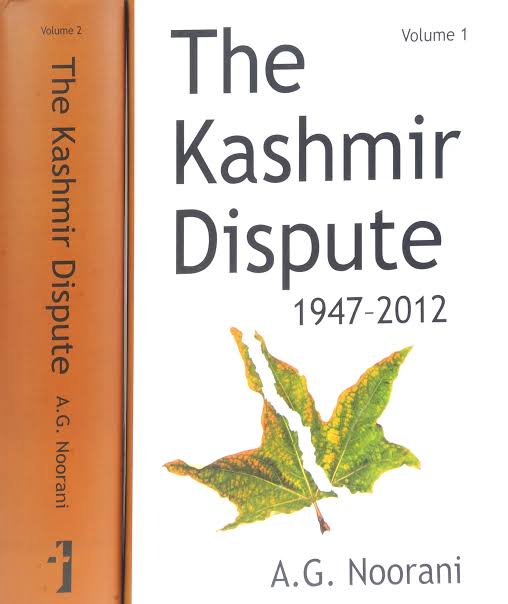

You can disagree with Noorani but you cannot dismiss his insights based on archival and contemporary documents. Take for instance, his two-volume treatise titled The Kashmir Dispute (Tulika Books, New Delhi, 2013) Part 1 in which, as the publisher puts it, Noorani ‘traces the complex history of this long-standing dispute, and the political discontent and dissent surrounding it _ relating to the question of the accession of the State of Jammu & Kashmir to the Union of India.’ Volume 1 has 153 pages of the main text and 134 pages of contemporary and historical documents.

His engagement with the Kashmir issue began when he was a young lawyer at the Bombay High Court in the 1960s. Iftikhar Gilani gives a glimpse of this in his article in the latest issue of Frontline: “Noorani’s involvement in the Kashmir issue began with a crucial introduction by Mridula Sarabhai, a rebel Congress leader and sister of eminent scientist Vikram Sarabhai. An ardent supporter of Sheikh Abdulla (the first elected Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir), Mridula Sarabhai was disillusioned with the Congress party’s treatment of the Kashmiri leader. When Abdullah was arrested again in 1958 as part of the Kashmir conspiracy trial, a British lawyer decided to contest the case at the behest of Pakistan, However, New Delhi made it clear that it would not allow any foreign lawyer to appear before an Indian court. Sarabhai hired Noorani as part of Abdullah’s defence team in 1962. This introduction to Kashmir was a defining moment in Noorani’s life. He often recounted his first visit to Jammu, where he met Abdullah in the special jail, and described it as a moment that sparked his lifelong commitment to the region.’

Another work of astonishing scholarship and incisive expose of a sinister force that is out to destroy the idea of India: RSS: A Menace to India. (LeftWord Books, New Delhi, 2019) In the introduction to the book, Noorani not only sounds the alarm bell but also exudes a fair amount of optimism: “The poison has spread alarmingly since [the time Nehru told a meeting of officers as far back as 1964 that ‘the danger to India, mark you, is not communism. It is Hindu right-wing communalism’.] But the forces that spread it are not invincible. They can be defeated provided that those who oppose it are ready and equipped to meet the challenge at all levels: not least at the ideological level which sadly few care to meet. But ‘if the trumpet gives an uncertain sound, who shall prepare himself to the battle?’ What is at stake is not only the Indian Dream. What is at stake is the soul of India.”

But the sound from Noorani’s trumpet was not uncertain. It was loud and clear, and would serve as an ideological weapon for those who are prepared for the battle. This masterly work has 16 appendices running to about 100 pages. The section could have been much longer had the font size not been reduced for production related reasons.

I had the privilege of translating this book into Tamil (820 pages). Whenever I told Noorani about the progress of my translation work, he would say with his characteristic sense of humour, “My friend, your translation would be better than my English original!”

Here is list of books that exemplify the range of subjects that was deeply interested in and extensively researched on: The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour; Savarkar and Hindutva, The Babri Masjid Question 1528-2003: ‘A Matter of National Honour’, in two volumes; Constitutional Questions in India: The President, Parliament and the States; Islam and Jihad: Prejudice vs Reality; The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice, Constitutional Questions and Citizens’ Rights; Indian Political Trials 1775-1947; India-China Boundary Question 1846-1947: History and Diplomacy; Jinnah and Tilak: Comrades in the Freedom Struggles, Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir; Islam South Asia and the Cold War, the Destruction of Hyderabad, Destruction of the Babri Masjid: A National Dishonour.

One can go on writing about Noorani. Only a comprehensive biography or a compendium of his writings can do justice to the greatness of a man of his stature in all his varied dimensions. Ravi Nair, a freelance journalist, offers some hope in this regard. Writing on his association with Noorani in the online portal Leaflet, he has this to say: “When I became more familiar with international human rights law, Noorani and I cooperated on many issues. He was generous in his praise of my work in many of his articles. He wrote a fulsome paragraph in this magnum opus on the RSS on my efforts at the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations to deny membership to the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP).

My organisation, the South Asian Human Rights Documentation Centre, jointly authored with Noorani a book titled Challenges to Civil Rights Guarantees in India, published by Oxford University Press in India in 2011. With Noorani’s permission, I have been working on anthology of his earlier writings. I am devastated that he will not be there to see its publication.”

My association with him came a full circle and it was food that completed the circle. Whenever we talked about good food he used to tell me that he would take me to ‘his’ Gymkhana Club if and when I visited Mumbai. He kept his promise in 2021 when I visited the city. It was a long luncheon meeting and he recalled our conversation about Karaikudi, the Chennai restaurant. I didn’t know that would be our last meeting.

A wonderful homage to an exceptional individual. Thank you, dear Vijay Shankar.

Vijay, thank you for a most befitting tribute to a writer who will be missed.

A vivid, nostalgic rememberance and tribute to the legend Noorani by Vijay Shanker . We too travelled along with thim in his memory lanes. Nice

Thank you Vijay sir , for this illuminating article . We could see the creative essence of both Noorani saab as well as you through this .. and of course , your deep bonding and camaraderie .. big salute to both of you sirs …

A touching piece that embraces the rigour, vigour, vastness, intensity, doggedness and acumen of this man of letters, this man of the match of letters.

Thank you for writing and sharing it.

Bests