What the US proposal to break up Google means for tech monopolies

On November 22, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) proposed a set of solutions to end Google’s monopoly on online search and related advertising business. This came three and a half months after US District Court Judge Amit Mehta’s historic verdict that Google had unlawfully kept a monopoly on the internet search and search advertising markets. “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” the ruling stated, marking the end of a trial dubbed by many as a “battle for the internet’s soul.”

The DOJ’s proposed remedies seek to put an end to Google’s illegal practices in the online search business, allowing competitors and newcomers to enter the market. The proposals include plans to strip Google of control and ownership of the Chrome browser and Android operating system.

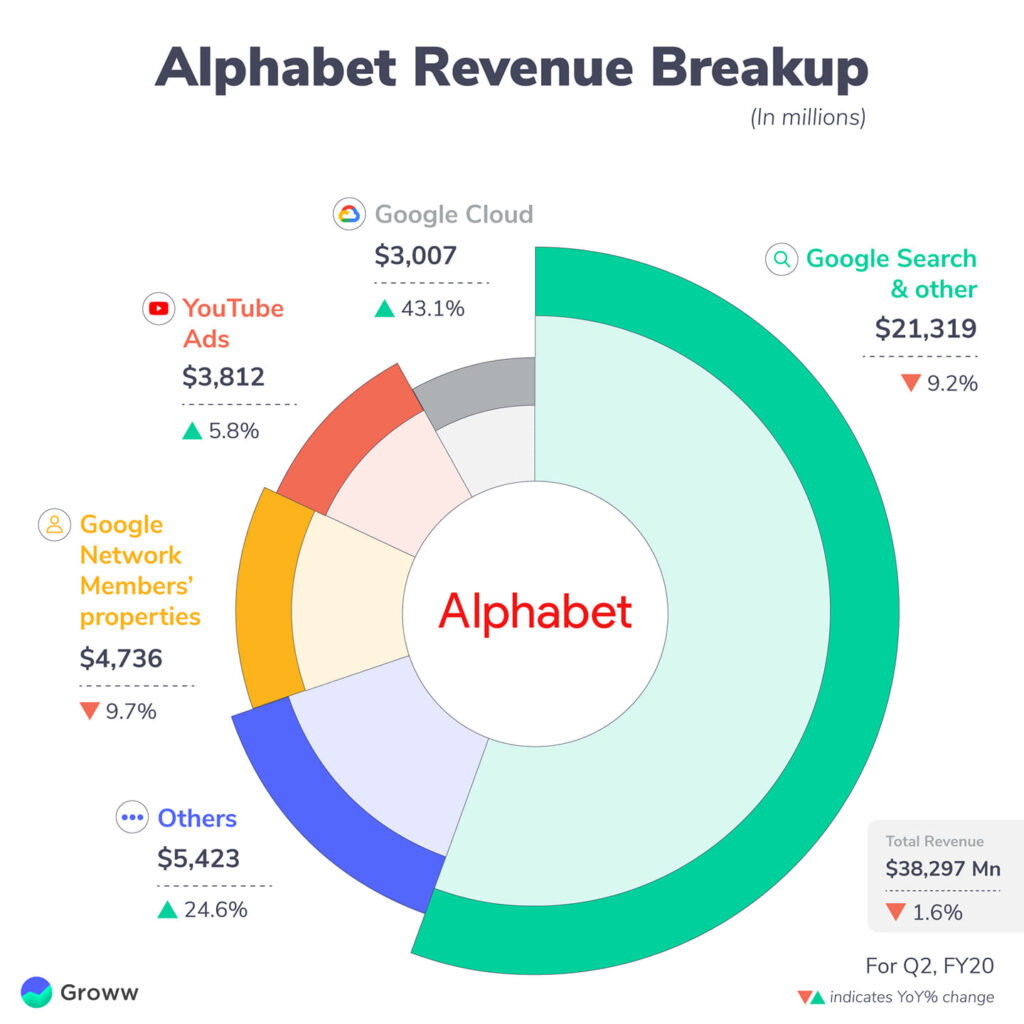

If the court accepts these remedies, the company’s operations will suffer significantly. Google’s parent company, Alphabet, is one of the world’s largest corporations thanks to search advertising revenues. In the third quarter of the current fiscal year, Google search advertising revenue was $49.4 billion, up 12% from the previous year. Advertising accounted for about 74% of Alphabet’s total revenue. Three-fourths of this advertising revenue is from Google search business.

In recent years, the technology industry has come under increasing scrutiny for potential anti-competitive practices. This antitrust case against Google is among the most significant of these legal battles. It was filed by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) during the previous Trump administration.

The outcome of this case will have a significant impact on how emerging digital technologies shape the market. This case also highlights the relevance of antitrust laws in limiting the unchecked expansion of corporate power in market economies.

United States et al Vs Google 2020

The DOJ sued Google in October 2020, alleging that it has been illegally monopolizing the markets for search services and advertising in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act. Later, several states in the United States filed similar claims, which were all combined into one lawsuit.

The plaintiff claimed that Google, which began as a scrappy startup providing an innovative internet search engine twenty years ago, has evolved into a monopoly gatekeeper for the internet. It has been able to do so by employing anticompetitive tactics to maintain its monopoly on internet search services, search advertising, and general search text advertising.

The most effective way for a general search engine to ensure de facto exclusivity is to become the default search engine on mobile devices and computers. Users rarely change their device’s default settings. The DOJ alleged that Google paid a sizable portion of its ad revenue to major phone manufacturers, distributors, and browser developers to ensure it was the default engine. This enabled Google to create “continuous and self-reinforcing monopolies in multiple markets.”

According to the DOJ, Google effectively managed to own internet searches with these exclusionary agreements and its anticompetitive conduct. General search engine competitors lack the necessary distribution, scale, and product recognition to compete with Google.

Google used this monopoly to make money from search-related advertising businesses, the DOJ said. Complex self-learning algorithms are required to determine the most potential ads that maximize revenue and the best results for each search. The successful implementation of such algorithms requires a massive data trove that can only be obtained through a monopoly on internet searches.

As expected, Google categorically denied these charges. The lawsuit failed to take into account the high-tech industry’s competitive dynamism, which benefits consumers, according to the company.

The trial and verdict

The pretrial discovery phase, which ran from December 2022 to March 2023, saw a large amount of evidence presented. A nine-week bench trial followed, during which top executives from Google, Microsoft, and Apple testified. After carefully considering the testimonies and evidence, the court found that Google is a monopolist and has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act. It upheld the majority of the plaintiffs’ claims.

The court determined that Google possesses monopoly power in the general search services and general search text ad markets. It attained this status by entering into exclusive, anticompetitive distribution agreements with Apple and other major players. Judge Mehta also noted that “Google has exercised its monopoly power by charging supra-competitive prices for general search text ads,” and this “allowed Google to earn monopoly profits.”

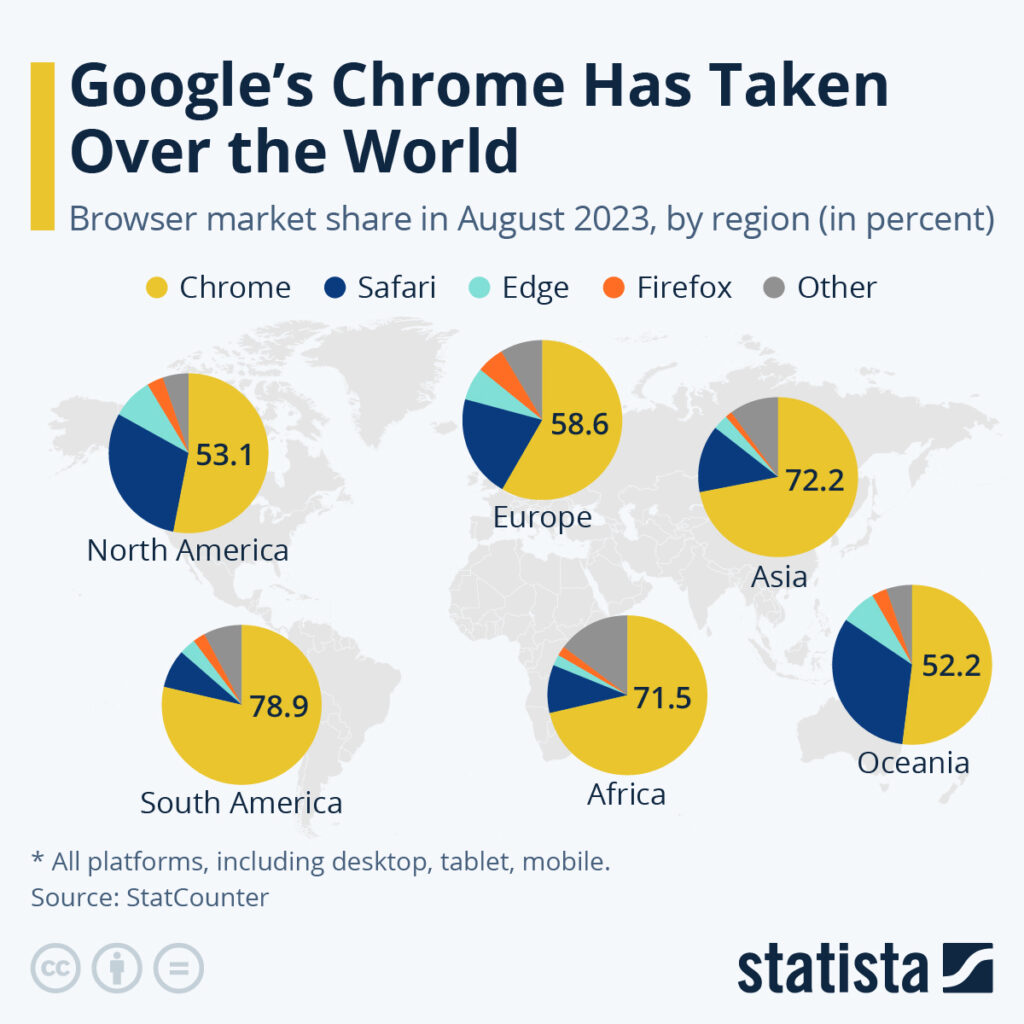

Google’s monopoly in the online search market is largely due to two products it developed: the Chrome browser with 67% market share and the world’s most popular mobile operating system, Android. Both products use Google search as the default search engine

Judge Mehta determined that the “default distribution” is a “largely unseen advantage” Google has over its competitors. He noted that Google spent $26.3 billion on traffic acquisition in 2021 alone. This is four times the total amount of money the company spent on all search-related costs, including research and development.

Key remedies proposed by the DOJ

As previously stated, the remedies outlined in the DOJ’s initial proposed final judgment for this case last month, if accepted, will have far-reaching consequences.

The first set of remedies includes proposals to end Google’s exclusionary agreements with third parties. This essentially means that Google would have to stop paying other companies, such as Apple, to include its search engine as the default in their products.

The most crucial remedies are those that prevent Google from excluding competitors by leveraging its ownership of products like Chrome and Android. The DOJ proposed that Google sell Chrome to a buyer chosen at the plaintiffs’ sole discretion.

On Android, Google has two options for not promoting its own services and undercutting competitors. It can either divest Android like Chrome or adhere to the detailed requirements provided in the judgement to prohibit self-referencing.

If Google selects the second option, there will be an assessment of the effectiveness of this decision five years after the judgment. If it turns out that Google’s compliance with the requirements has not resulted in a noticeable increase in competition in monopolized markets, it will have to devest Android. Or Google must demonstrate that its continued ownership of Android did not significantly contribute to the lack of a substantial increase in competition.

Furthermore, Google would be prohibited from investing in or purchasing “any search or search text ad rival, search distributor, or rival query-based AI product or ads technology.”

Another notable proposal is for Google to syndicate its search data, ranking signals, and search results to competitors for a marginal fee for ten years. This would allow rival search engines like Bing and DuckDuckGo to improve their products and compete more effectively with Google.

Some proposals benefit the advertisers too. The DOJ has proposed that Google give advertisers greater transparency and control over the performance and cost of their ads. This includes allowing advertisers to export their search text ad data so they can easily switch to competing platforms. These remedies will help to break Google’s monopoly on search text ads.

The US antitrust lawsuits: history of mixed results

Will the history of previous antitrust lawsuits provide any insight into the possible outcome of this case?

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first antitrust law in the United States. The law got its name from Republican Senator John Sherman, its primary author. At the time, public opinion was turning against the unfair monopolizing practices of large corporations. The breakup of Standard Oil in 1911 was one of the most prominent early antitrust victories.

Since then, antitrust lawsuits in the United States have produced mixed results. The Clayton and Federal Trade Commission Acts, enacted in the early twentieth century, strengthened antitrust laws. However, after the 1970s, government antitrust enforcement largely took a back seat. By then, the neoliberal ideology that champions an unrestricted free market had triumphed.

Even so, the antitrust tradition in the United States had not died completely. The 1974 lawsuit against AT&T resulted in the company’s split into several smaller entities in 1984. At the time, the company held a monopoly on the telephone business in the United States. The split provided enormous benefits to customers and fueled subsequent telecommunications innovations.

But the current Google lawsuit is more reminiscent of the 1998 antitrust case against Microsoft. The complaint alleged that the company was bundling its web browser, Internet Explorer, with the Windows operating system, preventing rival Netscape from entering markets. The court determined that Microsoft violated Sherman Antitrust Act provisions and asked the company to divide it into two separate entities. But Microsoft appealed to the decision. It ultimately avoided splitting and instead started sharing programming interfaces with other companies.

Google also will appeal. Reacting to the DOJ’s proposals, Kent Walker, President of Global Affairs and Chief Legal Officer at Google & Alphabet, wrote that “DOJ chose to push a radical interventionist agenda that would harm Americans and America’s global technology leadership. DOJ’s wildly overbroad proposal goes miles beyond the Court’s decision.” He stated that Google is in the early stages of a lengthy process and will file its own proposals next month, with a broader case coming next year.

Some commentators are of the opinion that Judge Mehta may not fully accept the DOJ’s proposals. They believe the court will settle for less severe remedies rather than ordering the breakup.

Another factor that will have a bearing on the outcome of this case is the new Trump administration’s position. Ideologically, it favors deregulation, and one of its major concerns is the ongoing trade and tech war with China. However, the lawsuit began during Trump’s first presidency, and he has never had a favorable opinion of Google. Early this year, Vice President-elect J.D. Vance also tweeted that the breakup of Google is long overdue.

But recently Trump seemed to have changed his mind. In a recent interview, he stated that breaking up Google is a very dangerous thing, especially in the light of threats from China.

It appears that the state’s ideological predilections, realpolitik concerns, and leaders’ personal biases will all play a role in the case’s final outcome.

Wider implications

Regardless of the outcome, the Google case will influence the current wave of litigations against tech companies around the world. Regulatory agencies in the US, Europe, Australia, China, and India are suing big tech companies for their market dominance and business practices. Judge Mehta’s ruling that Google is a monopoly provides impetus to these cases.

What is it about big tech companies that has sparked global discontentment? States of all political stripes, from Western capitalism to socialist China, seek to regulate these companies in similar ways. It reveals something about the emerging digital economy.

For starters, the very nature of internet-based businesses precludes free market competition. In these industries, as more people use a product or service, its value increases. This phenomenon, known as the “network effect,” allows only market behemoths to dominate and reap massive profits, making it difficult for new companies to enter and compete in such industries. Google is just one example.

Secondly, the digital revolution has dramatically altered both people’s daily lives and market capitalism beyond recognition. In the process, technology companies have evolved into colossal platforms. They are now formidable forces wielding extraordinary power over people’s wants, needs, desires, preferences, and opinions. What gave them this power was the massive data extraction made possible by digitization in all aspects of life, combined with algorithmic control.

These transformations were not without negative consequences. With their enormous power, these platforms pose serious threats to people’s security, privacy, and liberty. And they challenge and disrupt traditional market models through previously unknown rent-seeking behaviors. While some critics see this as capitalism gone rogue, others see it as capitalism being transformed into a new system reminiscent of feudal fiefdoms. Either way, one thing is certain: this represents serious ruptures in contemporary global capitalism.

Another issue is that despite spectacular technological advances, the global economy is in a long-term stagnation. Indeed, since the 1970s, the global economy’s average annual GDP growth rate has slowed. Historically, technological advancements provided long-term economic stimulus and helped them recover from recession. It appears that the current digital technology revolution is unable to provide such stimulus to the economy. However, at the same time, the large tech companies have become the world’s largest companies in terms of revenue and market capitalization, allowing unprecedented accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few.

These issues make nation-states’ relationships with major technology companies uncomfortable. On the one hand, governments cannot ignore the negative consequences of these corporations’ monopolistic power: stifled competition, disruptions to traditional market models, and the impact on people’s lives, such as threats to civil liberties and privacy. But on the other hand, the enormous wealth of these companies and the strategic importance of the new digital technologies in the increasingly polarized world make them the most desirable partners.

It is not surprising that the dilemmas of this love-hate relationship are increasingly evident in ongoing regulatory efforts to control big tech.