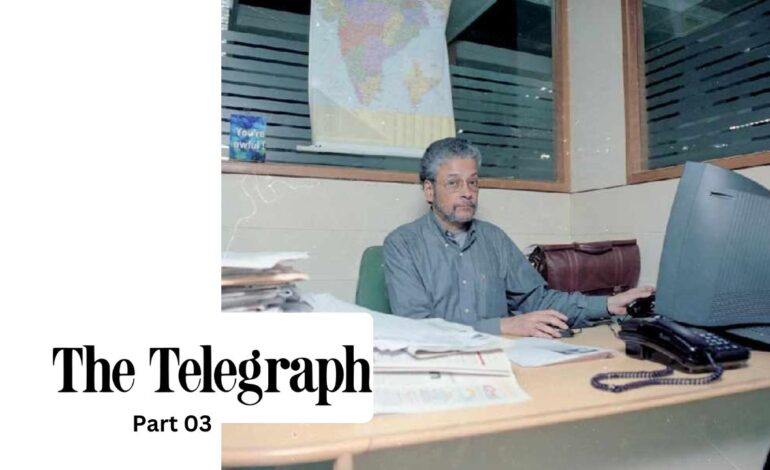

The following is the third part of a tribute to Deepayan Chatterjee, who transformed The Telegraph in the late 1990s and produced some of the most breathtaking news pages in India from 1997 to 2006 as the deputy editor in charge of news and played a key advisory role until 2016 when he retired. Chatterjee passed on March 3, 2025. This part covers apology, our home, the review and rut of history.

Apology

Rajagopal: Several newspapers have the inexcusable habit of hiding corrections in the Siberia of pagination, calling corrections “clarifications” and flashing the fig-leaf of “the error is regretted” when caught red-handed. This virus still runs wild in many newsrooms.

One of my proudest takeaways from Deepayan’s newsroom was the format he laid down for corrections. Don’t make lame excuses. Call a spade a spade: a mistake is a mistake, it is not an error. We apologize for the mistake. It is not enough to say “the error is regretted” as if God is issuing a commandment from high up.

I consider this policy one of the most important legacies of Deepayan because it shows how much he respected readers. Sadly, few newspapers in India follow such a policy these days.

Harshita: Here I will add one more point. While Deepayan made us step forward and take ownership of our mistakes, he also asked us not to shout from the rooftop when a report we had carried was proved right or when other newspapers followed up on a story that we broke. Under him, you never crowed.

Our Home

Rajagopal: When the ABP office caught fire in 1999 and we had to move across the road to the classified section to bring out the paper that night, we were stuck for a headline. As usual, Deepayan did not take long to scrawl on the headline sheet: FIRE ENGULFS OUR HOME.

But there was a problem. Possessive adjectives and pronouns were a no-no in headlines then — made all the more sensitive by the fact that we were reporting about the publisher of the paper. Editor Aveek Sarkar, Arup Sarkar and others were seated in another room around a small table that would function as their office that night, the devastating fire having ravaged the top floor of the ABP headquarters. Deepayan sent me to the table with a laser print of the page: “Show Aveekbabu the page. I am a bit iffy about the ‘our’ in the headline.”

I walked over and showed the page. Aveek Sarkar glanced at it and handed the print to Arup Sarkar. Usually tongue-tied, I cheated Deepayan and framed the best question of my life: “‘Our home’ in the headline is very good, isn’t it?” Deepayan had not assigned me to ask that. He wanted me to ask if “our” is all right as it goes against the usual headline norms.

“I suppose it can be excused for today,” Aveek Sarkar deadpanned. When I turned with the satisfaction of having accomplished the mission (our future was in doubt and my father had called me during the day from Trivandrum, asking if he should send money as he saw on TV smoke rising from the gutted floor of ABP. And here I was, whooping in silence about a headline!), Aveek Sarkar called me back. He stood up, placed his hand on my shoulder and told me: “Tell Deepayan that I thank him.”

Aveek Sarkar knew. It was crystal clear. He had figured out that only Deepayan could have given such a headline. ABP was home to Deepayan.

In hindsight, it was probably then that I realized that I would never be able to leave Calcutta on my own.

Harshita: Deepayan made The Telegraph home for many of us. It was our comfort zone, where we could speak our minds, where we did not fear being judged or misunderstood, and where we looked out for each other. An illness, a wedding, a school admission – we relied on each other for everything.

A friend and former colleague, Chandrima Bhattacharya, remembers how Deepayan, a tentative driver, drove her to the hospital for an emergency after a surgery. Another time, he loaned money for the hefty deposit to be paid for a child’s school admission. Devadeep Purohit has written about how Deepayan was with him at the hospital when his twins were born. Sujan Dutta has written about how Deepayan held his hand as he was losing his young son. He was the elder who holds a family together, through thick and thin. He was our cementing force.

I remember the New Year’s Eve when he hung around in the office after the paper had gone to bed. The pages were released much earlier than usual but he was still there after midnight. I asked him why he wasn’t going home. He did not reply but stayed till the end of night shift and took the 2.30am drop with us. Only Raja and Sumit Dasgupta knew that it was his last working day as deputy editor. He went on leave after that and returned to tell us he was stepping back from the daily grind. He called each of us into his room to break the news. I found myself fighting back tears, it seemed that the ground had shifted under my feet. I was not the only one who felt this way.

The Review

Rajagopal: Once Deepayan withdrew from active news operations and moved on to a consulting role but never too far from the newsroom, Aveek Sarkar asked him to do a daily review of The Telegraph. What followed was a master class in journalism.

Logbooks (in which the desk would enter page release timings, and editors would rip apart the paper by pointing out mistakes) have always been a nightmare for the desk. Anyone could see the book, which was actually a graveyard of reputations because most colleagues could figure out who had been singled out for the roasting each day.

But Deepayan’s review was different. Of course, it was merciless but he never went after individuals and always came up with a far better alternative if he criticized a news decision, placement, story, intro or headline. In fact, one of the few private mails he had sent me was related to the review. Deepayan was worried if the review was hurting some of his colleagues, which was not his intention.

In that mail, he also paid me a rare and great compliment: “I don’t hesitate to say anything I feel about the main section in the review because I have confidence in you. But if you think I’m being too harsh on (a particular section of the paper), please let me know….”

It would be great if ABP publishes the Review as a book with visuals of the actual pages that had been flagged by Deepayan, along with his comments. That would be a fitting tribute to his legacy.

Harshita: I hope the Review gets published. Deepayan gifted me my copy of Harold Evans’s Essential English, but I have learnt more from his daily reviews and the thrice-a-week training sessions he held for us. To quote from A Sub’s Manual that he drew up for these sessions, here are some of the qualities he said made a good text editor: “Sympathy, insight, breadth of view, imagination and a sense of humour.”

Rut Of History

Rajagopal: Deepayan rarely, if ever, wrote anything under his byline. But he did play an important and active field role in the coverage of the Agra summit of 2001 when Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Pervez Musharraf held talks. The Telegraph had considerable presence in Agra: reporters from Delhi and Lucknow and Idrees Bakhtiar, the Karachi-based journalist who covered Pakistan for The Telegraph from the 1980s. Deepayan decided to go to Agra, too, because summits do not care much for newspaper deadlines and he wanted to clear copies from the spot and at regular intervals.

We did not have mobile phones then. Deepayan would call me on the landline and tell me when he would call me next so that I could be near his office room to take the call. The calls from Agra were some of the most difficult I have had with Deepayan. They were also an eye-opener although I had known Deepayan for nine years by then.

I could make out Deepayan was disturbed when he called me. Several TV channels were reporting drivel like “talks were held in a constructive manner”, etc, and spewing the usual hyperbole. But Deepayan said that this was not the mood at the venue. Idrees Sahab also told him that something was wrong. More than worrying about what we should report, I was concerned about Deepayan’s despairing tone. It was then that I realised how deeply he cared about the need for peace between the neighbours and how he was losing hope. That was a revelation for me.

The following day, Musharraf held his infamous breakfast meeting with select Indian editors, unethically telecasting it live in Pakistan without telling the participants and pulling a PR stunt on the Kashmir issue. Many felt that the showman dictator had the Indian editors, except Prannoy Roy and a few others, for breakfast. Idrees Sahab was right. The talks were not going well and Musharraf had decided to gain maximum mileage back home from the misadventure in Agra.

When the summit ended, Deepayan and the team of reporters wrote one of the saddest reports in my career. Since the collapse of the talks was widely reported by TV channels through the night, Deepayan chose the delayed intro for the report that appeared under the sterile “our special correspondent” byline.

The report began thus: “History, President Pervez Musharraf will realise after tonight, is not easy to make. It’s as difficult to break.

“Years of mistrust and suspicion prevailed at the end of the summit at Agra, described by President K.R. Narayanan the other day as a city of love and reconciliation, as hour upon hour of talks between Musharraf and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and between the respective delegations did not yield the document the two sides had hoped would lay the ground rules for future interaction.

“The summit ended without a joint declaration that would have tied the leaders down to certain positions. Even the modest expectation of a joint statement that would have simply said that Musharraf and Vajpayee discussed so and so issues also did not come at the end.”

The conclusion of the long report shows the care Deepayan devoted to the entire copy, including the very last line that was linked to the intro: “Musharraf had come to ‘make history’. The only time he came close to history was when he visited the Taj.”

(This reportage is also an example of how informed opinion can be woven into copy without editorialising it.)

I could make out that Deepayan was depressed when he called to confirm whether I had got the copy. I confirmed it and paused. He realised that I was struggling for a headline. “Do you need a headline?” he asked. “Yes,” I replied.

Again, in the hour of adversity when he was down and out, the rapid response that showed how complete a journalist Deepayan was: “AGRA STUCK IN RUT OF HISTORY.”

The upcoming fourth and concluding part of the series covers DC, the Biscuit Girl, the mentor and big lessons.

To read blogposts from this tribute, click here.

“ AGRA STUCK IN RUT OF HISTORY.” .. that’s a headline and a half . Really awestruck by Deepayan’s personality and its creativity even in times of despair .? , salaams to Deepayan da , Rajagopal and Harshita

Oh! What an all-rounder Deepayan Da had been, as brought out by a transparent, painstaking recap by Rajagopal and Harshitha. Only someone who has lived thd pain of history sees the value of Peace. Salutations to a heartwarming tribute to Him.