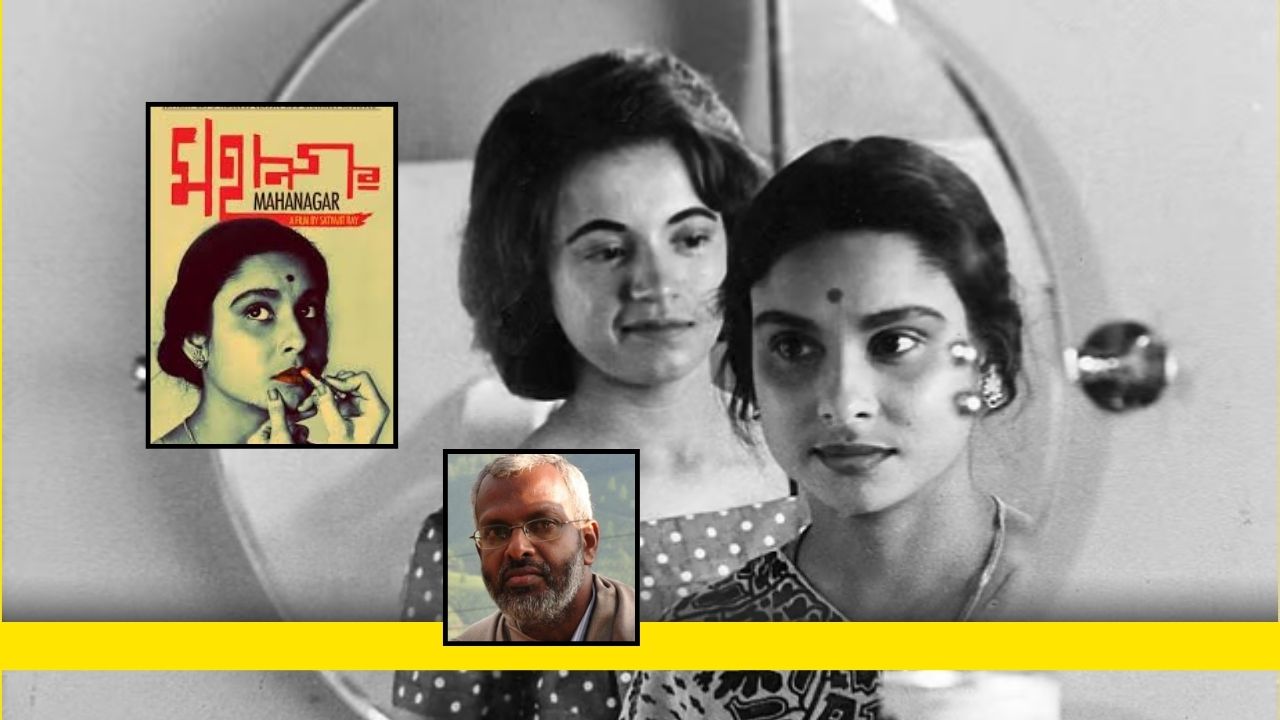

The following is the fourth and concluding part of a tribute to Deepayan Chatterjee, who transformed The Telegraph in the late 1990s and produced some of the most breathtaking news pages in India from 1997 to 2006 as the deputy editor in charge of news and played a key advisory role until 2016 when he retired. Chatterjee passed on March 3, 2025. This part covers DC, Biscuit Girl, the mentor and the big lessons.

DC

Rajagopal: Colleagues in Business Standard called him “DC”, abbreviating Deepayan Chatterjee. The irrepressible Nantooda (Nantoo Banerjee) would call him “Dipu”. I could never summon the courage to call him anything other than “Deepayanda” but I found the name “DC” fascinating. For headline junkies, the DC (double column) is the most challenging headline space in a newspaper. All other headlines are manageable because there is enough legroom. The single column has less width than the DC but single columns use smaller fonts, which means you have more space to play around with headlines. But the DC is a hard nut to crack, especially because the bigger fonts debut with the DC.

I used to think once that if I ever wrote a book on headlines, I would call it “DC”. That brings up the elephant in the room.

What did DC think of my headlines? The honest answer is, I don’t know. I know that he had staunchly advocated my name to succeed him. But knowing his elegance and sense of fair play, I suspect or speculate that Deepayan would not have agreed with my style of in-your-face, loud and editorialised headlines. It is a testimony to his greatness and grace that he never raised the topic with me. As editor, I also took several decisions that I know had pained Deepayan. Those are the private demons I have to battle on my own.

I would request Harshita not to comment on this topic as it would remain in the realm of speculation until and unless someone else comes forward with their account in case Deepayan shared his opinion with them.

Harshita: I will comment on this, Raja, because I did recently ask someone whom he was very close to what he had thought of the front pages. “Why are they editorializing so much?” is what he would say to this friend. To what extent he disapproved I do not know.

The Biscuit Girl

Rajagopal: When the Boxing Day tsunami struck in 2004, it would have been inexcusable if we carried anything else as the main story on the approaching New Year’s Day. Death and destruction marked every report in the previous few days and The Telegraph needed something to break the chain and offer a sliver of hope to the readers.

Deepayan then spotted the picture of the child at a relief camp, the stirrings of a smile and a few biscuit crumbs around her lips making it an unforgettable image. Deepayan wrote an entire Page 1 story based on that AFP picture, flying blind, without knowing anything about her and underscoring what many Indians and the world were doing to help those wrecked by the tsunami. The picture and story covered the full page. The headline gut-punched you as well as offered hope: CHILD, WHO ARE YOU? I AM THE DAY SOON TO BE BORN.

A quote below by the then President, APJ Abdul Kalam, captured the mood of the country: “I was thinking what to convey as New Year greeting to you for the year 2005…”

Under another headline, INDIA SHARING (yes, a political statement that put down the infamous “INDIA SHINING” slogan that was in vogue a year earlier), Deepayan wrote: “She runs in joy, the child in the picture. Like drops of sunshine, crumbs of a biscuit hang from her lips stretched by a widening smile. Four biscuits are clutched between her tiny fingers in one hand and a half-bitten one peers out of another. Having lost home, certainly – perhaps family members, too – the little girl at a relief centre at Cuddalore lights up the world around.

“Someone has reached a few biscuits to her.

“With a toll that is swelling beyond 125,000, the Christmas Day-after disaster is demanding of the world a relief effort it has never mounted before. And the world is responding as never before….”

Sympathy, insight, breadth of view, imagination…. You can see in the copy almost all the qualities, as Harshita pointed out, that Deepayan expected in a text editor. The front page had a graphic that listed the “Big Hearts” that donated money to the global relief effort. In the roster of crores donated by behemoth organisations, the last entry shone bright: “Sex workers in Maharashtra: Rs 13,000.”

Almost a year later, M.R. Venkatesh, who covered Tamil Nadu then for The Telegraph, tracked down the girl, Komalavathi.

The 2005 New Year’s Day Page 1, featuring the then unknown Biscuit Girl, touched lives in Calcutta in ways we had not imagined. Monidipa Mondal, then a Class XI student of Calcutta International School, wrote the following poem, inspired by the photograph in The Telegraph:

The Lost Mermaids

We called them our mermaids,

The little girls. Dainty little feet

Running bare about the shore, to greet

Father’s fishing boat home, or playing hadoodoo;

Unbothered by anything else

But the grains of gold and pristine seashells

Bordering the seamless blue ahead.

For they were children of the blue.

And that morning, the blue came to claim them back.

It took us too, our lives, our world, our home;

But to its realm we guests were unwelcome

And were flung back, upon this living hell

It carved for us. But on this battered shore

Will never play our mermaids any more.

The Mentor

Harshita: Deepayan built a newsroom that had depth and breadth. We were a diverse group, very different in our interests and temperaments and not always in agreement with each other, but there was room for everyone. He taught us the ropes and then set us free. He was like the trainer who teaches you to ride a bicycle, puts you on it and then lets you go, standing by watching, sometimes catching you before you fall and at other times helping you back on your feet after. He did not grab the handle and try to guide the bicycle’s course, but you always knew he was there and had your back. It takes immense confidence to be able to do that. When he stepped back, he left a newsroom that had at least three rungs of sub-editors who could bring out a decent edition independently.

Rajagopal: I am yielding this space to Harshita for two reasons. One, I could not have described Deepayan’s role better than the way Harshita has. Two, I don’t know where to begin and where to end. Ella Dutta, the art historian who worked for Business Standard, once said the way Deepayan and I worked together made her “jealous” – by then, only a year had passed since I met Deepayan. I cherish it as an invaluable compliment for me. If I write about how Deepayan mentored me, it will become an autobiography about the best years of my life.

The Big Lessons

Rajagopal: What was the biggest lesson Deepayan taught me? Always respect the reader, never stop learning and never forget the basics.

Deepayan never told me in as many words but this is what I learned from his work: respecting the reader does not mean giving what they want or pleasing them or massaging their ego or playing safe so as not to test them. It means sharing only information that you are certain is correct when you wrote it and have the confidence to tell the reader that you don’t have the full information and that you don’t know if something is true or not.

You are finished the day you think you are better than the rest and that you don’t need to learn anything. I emphasize this point because my narration above could create an impression that Deepayan was better than the rest or that others did not matter. That is far from the case. As I said, he never claimed that he reinvented the wheel. What he did was he never allowed us to forget how the wheel was invented in the first place by those who came before us and those who were far better than us. When I grew tired working on a headline, I thought about CP Kuruvilla, Deepayan, Aveek Sarkar, Arun Roy and many others who had the knack of making headline-writing look like child’s play and I kept at it.

With the deadline hanging over our heads and the clock sprinting, when a headline clicked into place, Deepayan would get off his chair with a spring in his steps, a glint in his eye and steel in his voice: “I got it. There is always a headline.”

Yes, there is a headline. Every story has a headline. Always.

Harshita: From Deepayan we learnt to work hard, to put the reader at the centre of everything we did as journalists, to think independently, to be unafraid, and to always look at the big picture. He also taught us to take responsibility for our mistakes, to be honest and never sugarcoat or deceive, and to lead from the front.

Deepayan drove a ramshackle white Zen, did not accept the membership of Tollygunge Club that ABP had offered him, and stayed firmly out of the limelight. He taught us that what we preach in the newspaper, we must practise in our own lives. It was because of him that I told my family we could not buy a diesel car after The Telegraph had run a campaign against vehicular pollution. That campaign against katatel, a lethal mixture of petrol, kerosene and naphtha used in autorickshaws, eventually helped reduce Calcutta’s air pollution.

He also showed us how to let go. How many people at the top of their game can step back like he did, at age 51, and never interfere? If there was anyone whose word Raja would have found difficult to brush aside, it was Deepayan’s. He knew that and never commented on the paper Raja edited, allowing his protégé the freedom to find his own voice and make his own mark. A secure and generous leader and a warm human being whose eyes sparkled and smiled, Deepayan was the teacher who shaped my life. He shaped many lives.

To read blogposts from this tribute, click here.

This four-part meditative or reflective memoir about the Journalistic qualities and days of Deepayanda of ‘The Telegraph’, and that too in a dialogue mode by two his former senior colleagues, R. Rajagopal and Harshitha Kalyan, has drained out the probability of any subjectivism to almost nil. A disguised blessing in itself when we wish to speak truthfully about people and places.

This, notwithstanding the warmth and candour with which they have recounted the story for us. It also has several lessons for those in the profession and even outside it. A very rare and excellent tribute indeed to Deepayanda! Regards