From Free Trade to Trade Wars: Trump’s Tariffs and Growing Global Turmoil

Once upon a time, trade built bridges. Now it’s building walls.

Make way for a new chapter where trade talks sound more like threats and globalisation is gasping for air. Trump’s tariffs haven’t just rattled markets, they’ve shaken the very idea of a borderless economy. World leaders are sounding alarms, alliances are shifting, and suddenly, everyone’s asking: aren’t we moving towards a global shift?

In a week marked by rising global tensions and economic uncertainties, world leaders are issuing distinct warnings as the U.S. President Donald Trump’s new tariffs set off alarms across continents. With the United Nations voicing urgent concern and the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer declaring the “end of globalisation as we know it,” the world is struggling with a historic moment in the evolution of international trade. This isn’t just another bump in the road. For many, it signals a sharp rupture in how the global economy is structured—and raises serious questions about what lies ahead.

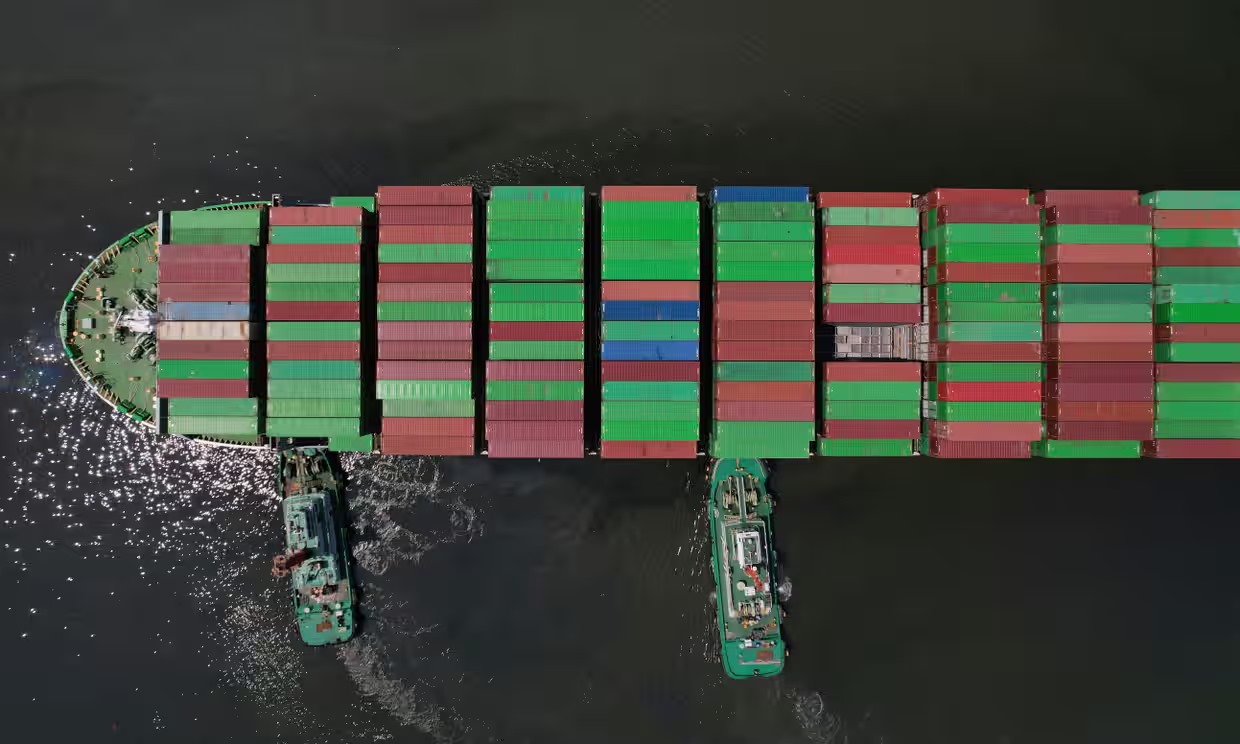

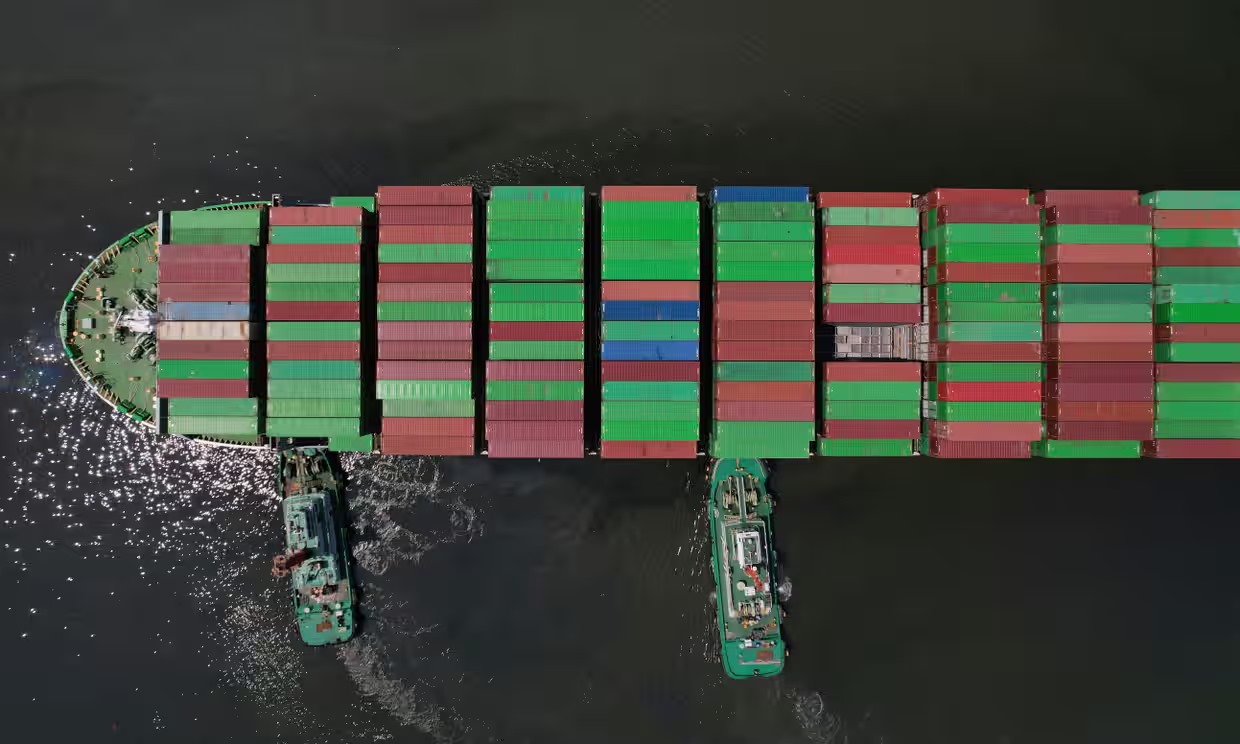

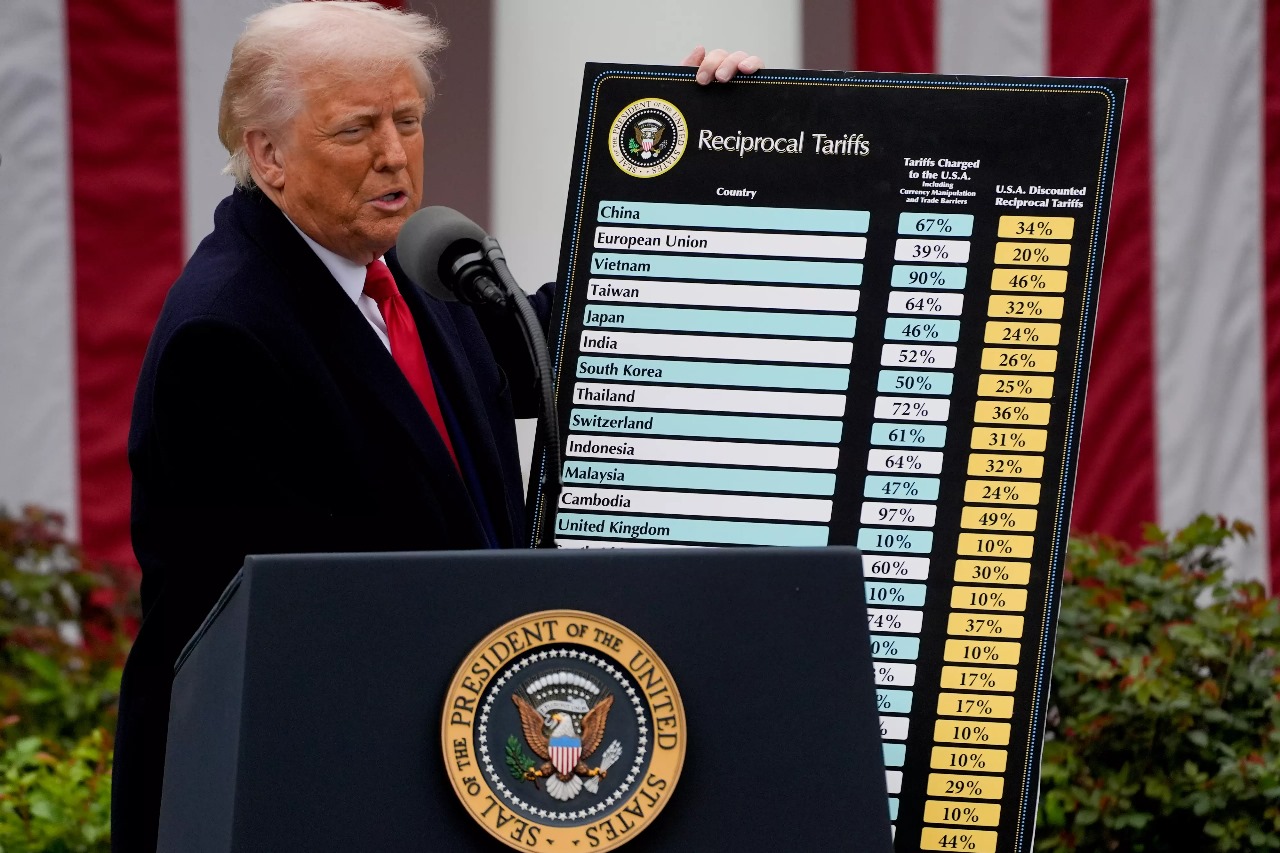

In a move that surprised many, U.S. President Donald Trump reimposed and expanded tariffs on a wide range of imported goods, particularly targeting China, the European Union, and several developing economies. Trump’s administration claims the tariffs are significant to “rebalance unfair trade” and protect American workers. Markets across Asia and Europe tumbled in response, and major exporters have begun amending supply chains. These developments mark the continuation of Trump’s “America First” economic vision, which deeply diverges from the multilateral, cooperative trade philosophy that has been prevalent in the last three decades.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has responded with sharp criticism, stating, “Nobody wins in a trade war.” Guterres emphasized that history has shown protectionist policies often backfire, further leading to inflation, instability, and hardship—especially for third world economies and developing nations. “These tariff hikes will not only escalate tensions but will also disproportionately hurt the most vulnerable—the poor, the working class, and small economies that rely heavily on export markets,” he said. The UN chief also drew attention to how this could worsen the already fragile global recovery post-pandemic and amid ongoing conflicts. With many nations still dealing with the repercussions of COVID-19 and regional wars, the new trade barriers could push some economies into outright recession.

In a landmark statement, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer declared that we are witnessing “the end of globalisation as we know it.” The remarks, made amid growing concern over the Trump administration’s unilateral economic aggression, highlight a significant departure from the UK’s traditionally free-market stance. “The international trade order that lifted millions out of poverty and shaped the post-Cold War world is now in retreat,” Starmer said. He also announced the UK’s readiness to act in coordination with allies to stabilize the global economic environment. He indicated that Britain could introduce its own trade measures to shield its economy and support multilateral institutions.

While condemning the tariffs, China appears to be viewing the moment as a strategic opportunity. Beijing has expressed deep opposition to the U.S. measures, warning that retaliation is inevitable if negotiations fail. Yet, Chinese analysts suggest this trade war could allow Beijing to accelerate diversification efforts—pushing trade further toward Asia, Africa, and Latin America. It could also help China champion a new trade framework that reduces dependency on U.S. markets and institutions. However, there’s concern as well. China remains the world’s largest exporter and is highly integrated into global supply chains. Disruption at this scale could undermine key industries, particularly tech, textiles, and electronics.

Further complicating the picture, Iran has refused direct nuclear talks with the United States, warning regional actors not to support any U.S.-led economic or military aggression. While separate from the trade issue, Iran’s hardline stance contributes to a broader scenario of global distrust and fragmentation. Iranian leaders suggested that Trump’s re-election and aggressive foreign policy encourage destabilizing moves. Any economic sanctions or trade restrictions in the Middle East could have ripple effects—particularly on oil prices and shipping routes.

To understand how we got here, it’s important to revisit the history of globalization.

The late 20th century saw an unprecedented rise in economic integration. The fall of the Soviet Union, the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995, the rise of emerging economies like China and India, and the digital revolution all contributed to the rapid expansion of global trade. Multinational corporations and bilateral agreements flourished. For many, globalization meant prosperity, consumer choice, and growth. But for others, it meant job losses, wage stagnation, and cultural homogenization. The 2008 global financial crisis exposed structural weaknesses in the global economic system. Though it didn’t end globalisation, it marked the start of growing skepticism. Populist leaders from Trump to Brexit advocates joined this discontent, campaigning against trade deals, foreign labor, and international institutions. Now, with Trump’s second round of tariffs and major world powers reacting defensively, it appears we’re witnessing the culmination of that backlash.

While the debate around trade wars often revolves around economic strategy, the real casualties are often invisible: small business owners, farmers, low-wage workers, and vulnerable communities in developing countries. Tariffs make goods more expensive. For example, when U.S. companies are forced to pay more for imported components, they either raise prices for consumers or cut costs. Developing countries that rely on exporting agricultural products or textiles to the West may suddenly find themselves locked out of the markets they depend on. As Guterres pointed out, these consequences often deepen inequality and hinder sustainable development goals (SDG).

Another casualty in this trade war is trust, particularly in global institutions designed to mediate disputes and coordinate economic policy. The World Trade Organization (WTO), which once served as the backbone of the post-Cold War trade regime, has been sidelined in recent years. Trump’s administration has consistently undermined the WTO, refusing to pursue unilateral measures. This has weakened one of the only international mechanisms capable of resolving trade conflicts peacefully. Without credible institutions, trade disputes are more likely to escalate and go out of control, possibly sparking broader economic or even military conflicts.

With the rules-based international trade order crumbling, the world faces a critical crossroads. One path leads to a new era of economic fragmentation, where nations prioritize short-term gains, protectionism, and bilateral power politics over global cooperation. On the other hand, the second path demands a reinvention of globalisation itself. It would involve reforming trade institutions to make them more equitable, updating trade rules to incorporate environmental and digital realities, and addressing the structural inequalities that fueled the backlash in the first place. Keir Starmer hinted at this and implied that while the era of unregulated, hyper-globalised capitalism may be fading, the need for shared rules, mutual benefit, and economic diplomacy has never been more important. Trump’s tariffs may have triggered this round of tension, but the underlying issues run much deeper. As UN chief António Guterres starkly warned, “In this trade war, all will lose.” With China recalibrating, the UK pushing for international action, and the developing world bracing for impact, the choices made in the coming months will shape global trade for decades. Whether we move toward a cooperative, inclusive system—or retreat into nationalism and conflict—remains to be seen.

But one thing is certain: the age of globalization, as we knew it, is over.