A Chair, Bruised But Still Standing And Speaking

“Walking point” is a dreaded task in the army – the soldier on point takes the first and most exposed position in a combat formation. They are often the first to be ambushed, shot, blown up or captured. Of course, they must be valorous but often, there is no choice. “When your commander asks you to walk point, you neither say ‘yes’ nor ‘no’. You simply clench your teeth and do the job,” one German paratrooper has written, unlike in most Hollywood propaganda movies and fiction.

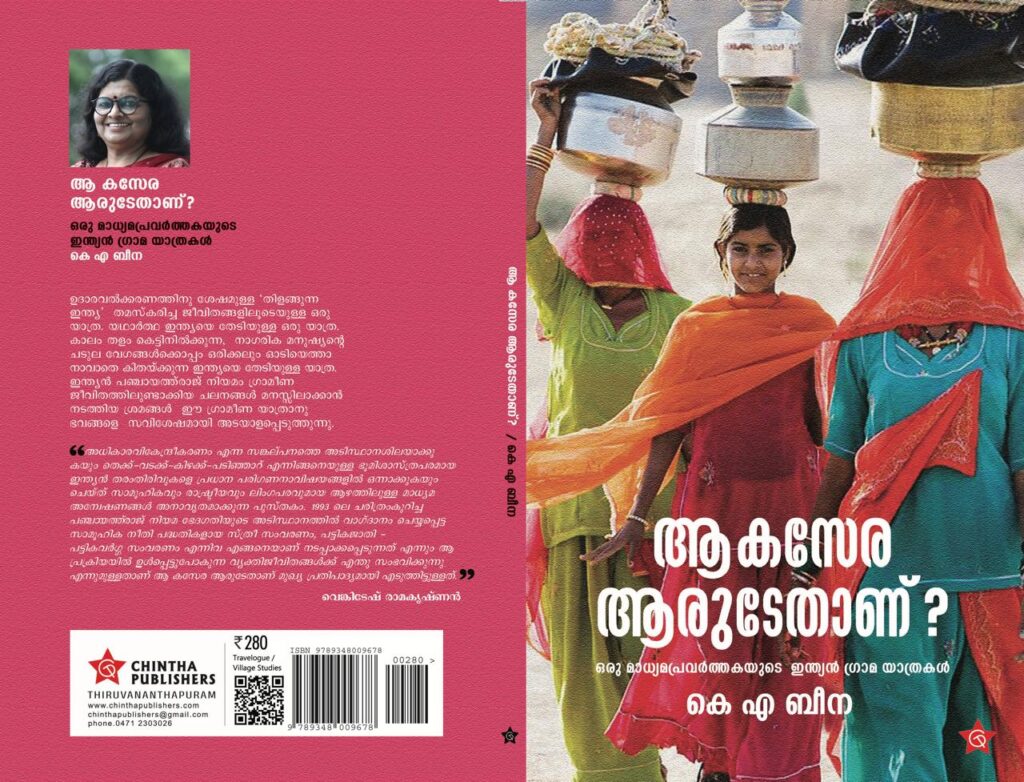

KA. Beena would, understandably, be horrified, if not outraged, at the martial reference in a response to her new book. Aa Kasera Arudethanu (Whose Chair is That?), brought out by Chintha Publishers. Aa Kasera Arudethanu is an assessment of the impact of the two amendments to the Constitution in 1993 that reserved seats for women and Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe candidates in local self-government.

The journalist in me cannot escape the news value of the book although it might have been a coincidence. The book is published at a time Kerala is discussing Sanatana Dharma. Beena’s book is a vocal response to advocates of Sanatana Dharma, reminding the reader that the atrocities revisited are not from a hoary past but from the time when most policymakers and decision-makers had come of age in India in the 1990s.

Dalits terrified of contesting elections for years, fleeing after filing nominations and dropping dead mysteriously in daylight after winning elections and elected candidates having to sit on the floor and leave the chair vacant for fear of antagonising the upper castes…. The list is long — and lashing. All because of the caste system and the varna system nurtured, aided and abetted by faith-based majoritarianism that seeks legitimacy through Sanatana Dharma.

I was reminded of the military phrase “walking point” because of the extraordinary people Beena has managed to track down and speak to. Like the soldiers walking point, these fighters were the tip of the spear, the first wave that took the full impact of the strikeback. And unlike many of the soldiers who do not have much choice once they enlist, the vanguard that Beena profiles volunteered to do so when few would cross the rubicon.

Sujatha Ramesh, Baluchami, Periya Karuppan… all paid a heavy price for breaking through barriers and stepping into a forbidden zone that had become the last mile of democracy in India. Their sacrifice is not limited to themselves but their families also continue to suffer. These leaders need not have plunged themselves headlong into the unknown when even the mighty Indian State had stopped dead in its tracks in the face of a caste- and prejudice-fuelled backlash. They could easily have minded their own business and continued to flourish. But they did not. Or, they could have been like Ganesh, who learnt to conform and survive.

It is rough and hard. There are few happy endings, which makes the original question more relevant and intriguing: why did they do what the others would not?

Beena met some of these gamechangers twice — and separated by several years. This is the holy grail of journalism: the rare willingness and ability to establish where the story went after the headlines died down. The course their lives took is not a pleasant picture — unlike the feel-good stories you read in the western media.

I think in the 1980s, a toddler sneaked out of his home in America and took his parents’ car for a drive, spooking cops who thought a driverless car was cruising down the road because the child was too short to be seen through the windscreen. The New York Times reporter who covered the phantom ride waited for years and was present when the child attained the legal age to apply for a driving licence and passed the test. The reporter accompanied the boy for the second drive — and the first legal — in the child’s life and filed a story that eventually made it to a collection of the best “human interest” stories in The Times in the 20th Century.

Related: Permanently On the Precipice: Sujatha’s Life As Panchayat President And After

A correction is in order. The road and mobility story made me realise that. Beena’s book does have some feel-good stories — and they are far more far-reaching than a story that originated from careless parenting and averted disaster by pure chance. Luck or chance had nothing to do with the women who cycled out of feudal shibboleths in Pudukkotta. It was nothing short of a revolution — and it has survived unscathed, so much so that a new-generation hospitality staffer was bemused by Beena’s interest in her cycling that has become a given in Pudukkotta now.

The journalist’s hawk eye picks out details others may miss: such was the demand for cycles after the collector launched the initiative that some women commandeered the cycles of the menfolk, which had an unexpected fallout. Men’s bicycles have a horizontal frame, which helped the women carry children on the frame and water on the carrier in the rear, which in turn helped the women stay away from home for longer hours and pursue income-generating vocations.

The other feel-good story is from Bengal where I lived for three decades. The 1993 experiment has worked well in Bengal — unlike in some other States where proxies, dummies and a “consensus” scam have undermined the original intent — probably because the stranglehold of caste has loosened somewhat, thanks to multiple social reform movements and the long years of the Left in power. The problem in Bengal appears to be linked more to power politics manifested in the denial of resources to panchayats where the Opposition is in power.

Beena’s style of writing that is remarkable for its clarity and absence of gimmicky language helps in providing what I felt was a fair assessment. This style of storytelling should be contrasted with the breathless celebrity journalism now in vogue and the rubbish in several mainstream publications that passes off as coverage of rituals in places of worship.

Overall, the picture that emerges post-1993 is one of success, albeit limited. I am still mesmerised by the plunge pioneers like Sujatha, Baluchami and Periya Karuppan took. I also cannot help but feel that the policymakers made an inexcusable mistake: they should have put in place a lifelong safety net to take care of these vanguard citizens and their families and at least the next generation.

We can’t fight centuries-old prejudices with a mere five-year plan. It requires long-term investments, perhaps spanning generations. You can’t leave your fighters behind and move on. A constitutional democracy should be able to afford it if it wants to graduate itself into a social democracy. This, along with the indispensability of education, is the lesson I learnt from reading Beena’s invaluable book. I hope the incumbent and future policymakers take note of this lesson.

Available to read in: Malayalam, Hindi