“When I remember all that now, it retches up a fourth-rate movie scene, stinking of vomit. Sometimes our lives seem more absurd than cinema, right?” A monologue that is swathed in irony. This is how Najeeb, the protagonist, thinks aloud about the wretched phase of his life in Benyamin’s celebrated novel Aadujeevitham (Goat Life). Days after the release of the Blessy-Prithviraj film based on this novel, as audiences began commenting on its classic structure and its international appeal, what strange thoughts, memories and experiences will this monologue conjure up in us?

A critical evaluation of the literary or artistic value of the film can be found in this remark from the novel. This monologue appears in the novel when Najeeb, imprisoned, remembers how when going abroad, as he was bidding farewell to his pregnant wife, tells his unborn child that he might only see him when he returns. While many readers who approach literature seriously see the novel Goat Life only as an average piece of writing, it went on to become a major bestseller in Malayalam and is now a part of Kerala’s literary history. And indeed, the narrator’s life, which he himself saw as a fourth-rate movie scene, is now an international film that has no parallel in the history of Malayalam cinema.

Goat Life, the novel, was not marked by startling experiments in the narrative, it did not have phenomenal philosophical dimensions nor was it characterised by uniqueness of language. Yet, the novel created an unprecedented readership record. Actually, it was Najeeb’s life, reproduced authentically throughout the novel that ensured its success. It is the emotional rollercoaster of a narrative of this intense life story, autobiography or biography called Goat Life that helped it cross the usually limited readership of literary works. When Blessy reworked the novel Goat Life into a cinematic form, it turned out to be something that actually helped him perfect his own medium.

On the day of the movie’s release, I watched the morning show with a bit of excitement and wrote a Facebook note that day – ‘Benyamin’s novel Aadujeevitham is based on the real life of Mr. Najeeb, whose intense suffering forms the narrative. Prithviraj’s Blessy-directed film based on this story had its first show today. Goats living goats’ life is only natural, however human life without even the dignity of a goat – a life of slavery – is in fact the darkest and harshest reality that Goat Life unfolds. The director and the actor – Blessy and Prithviraj – can be said to be recording the extremes of human experience, cruelty, tragedy, helplessness, misery and terror through this film. If Prithviraj’s Najeeb brings tears to our eyes unawares it is because it truly reminds us how ‘heavenly’ our lives are. It is the crowning achievement of a work of art. Similarly, the tenderness of the goats and camels in a couple of instances in the film left me speechless. So let me just stop by mentioning that Aadujeevitham is unparalleled in the history of our cinema’ the Facebook post said.

Now it comes down to the fact that there are some important reasons why a comparison of Goat Life with other films does not seem easy. It is a fact that the film adaptation of a work that has made its own name in literature has led to heated debates among Malayalees. But here Blessy, while doing justice to the real life story of Najeeb and also the narrative technique of the novel form, convinces us that cinema is basically a visual art.

When he appears in the title frame of the film with the goat, exhausted, in the dark, drinking water from the tank set up for his goats or when the film opens with a frame where we struggle to distinguish between the faces of the goat and the man, we see Blessy’s Goat Life establishing its identity as a unique work of art. It is because Blessy depicts Najeeb’s water world in his homeland and the Sandy desert he is forced into ingeniously, that we experience the heat and parched air of the desert land even in the air conditioned cinema hall.

The entire desert ecosystem accompanies Najeeb on his journey. Snakes as well as other creatures of the locales combined with the manifold lurking dangers of the desert. And, of course, there are the oases.The incredible hidden world of the desert, symbolising emptiness, struggle for survival and profound spirituality in many forms, has already been depicted in works like ‘Road to Mecca’. Still, a remarkably different emotional sphere and its conflicts manifest in Goat Life. There are very many instances of these manifestations in the movie. One of the striking images that would haunt the viewer for long is the one where Hakeem, parched and unable to find drinking water, spits up sand and vomits blood. In a sense, this is a sort of pronounced judgement on our wastefulness and exploitation of natural resources.

From Goat Life to the global ‘Survival Cinema’ Gallery

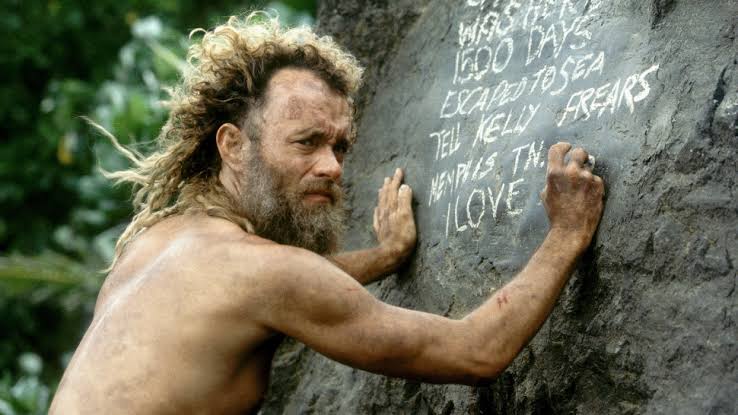

There are many international survival movies that come to mind in the context of Goat Life. Movies like Society of the Snow, The Revenant, The Impossible, 127 Hours, Alive, Everest, and Cast Away. The characters in such films take the viewers from their otherwise serene living circumstances to a visual experience that virtually takes them to the very brink of life and death. In other words, extremely dangerous situations and conflicts. At the same time, the fact also remains that survival movies are generally loved by audiences, no matter how painful the experience of watching them is. The main factor for this should be the empathy that the audience feels, while watching the adventurous situations and grave disasters depicted in the movies. This, combined with depictions of human bravery, endurance and the capacity to fight against big odds upholds the gritty human spirit, and this too works well with the audience. The celebration of the indomitable human spirit, which emerges, suddenly as it were, in these taxing circumstances, should be at the core of this viewer phenomenon. Knowing that real humans were involved in these survival stories adds to the context of the viewer experience and this enhances the viewer’s feelings towards the characters depicted in such movies.

A case in point is that the survival film The Revenant, which is based on a real-life story, like Goat Life. Similarly, Cast Away is another memorable film in this genre. Here, we see the character played by actor Tom Hanks’ struggling for survival against heavy odds, following an aeroplane crash, which crash-lands him in a deserted island. Hanks’ performance in this movie is subtle and nuanced in a heartrending manner. In Goat Life Prithviraj too has come up with an equally dedicated, subtle and nuanced performance. The very fact that he shed 36 kilos to become Najeeb in the movies is testimony to his hard work and dedication. In many ways, this absolutely stunning weight-reduction and the depiction of Najeeb, in what could be practically termed as a “new avatar”, is bound to redefine Prithiviraj’s acting career forever.

Hanks plays Chuck Noland, a systems analyst executive who travels the world. When the plane crashes in the South Pacific, he is stranded alone on a deserted island, fighting for survival at every turn. This is when the film takes the audience on an emotional journey and makes them sympathise with the hero repeatedly through the viewing. It can also be said that Hanks carries the entire film almost single-handedly. The film becomes a great illustration of how – and to what extent – one can stay strong even when everything is lost. We are reminded of this spirit when we hear Ibrahim Qadri’s words in Goat Life where he tells Najeeb that “we must walk, till we die” during the escape journey.

On the technical side, AR Rahman and Rasool Pookutty intensify the experience of the film. While Rahman’s song, ‘Perione Rahmane’, sounds like a prayer and a lament, it is clear that Blessy sets Najeeb’s faith-based survival effort in the background. Through this, the director also conveys the existential dynamics of Najeeb’s inner strength, which is rooted in his spirituality. Similarly Rasool Pookkutty’s sound mixing too deserves a special mention. Jimmy Jeanlouis who plays the role of Ibrahim Qadiri is definitely an unforgettable presence. Similarly, this film will not fail to give new opportunities to KR Gokul who plays Hakeem. Amala Paul, who plays Najeeb’s wife Zainu, secures their destiny and reminds us of Najeeb’s “aquatic life”. Cinematographer Sunil KS makes the visual language of Goat Life, a beautiful classic exemplar of the language of the heart of the Director Blessy. In the scene where vultures attack Najeeb as well as in the scene where Najeeb is seen to be celebrating as Arbab goes for wedding, the attention and skill of the director in Blessy is evident. The constant and crippling presence of the desert sandstorm, with its hideous sounds, also bears testimony to Blessy’s skills as a director.

Between Aquatic life and Desert life

Unlike in the novel, we do not see Hamid being taken back by Arbab from Sujesi prison in the film. Blessy, on the other hand, portrays Hakeem’s death and the unexpected disappearance of Ibrahim Qadiri more intensely. It also provides Prithviraj’s Najeeb with a parallel desert life of immeasurable, brooding loneliness. The portrayal of Najeeb’s lonely life is underscored in the novel when he starts giving the names of his loved ones at home and his village to the goats. But in the movie Blessy, portrays this through the cry of a black lamb, which seeks to help Najeeb, as well as through the tender eyes of a camel, which looks at Najeeb. Through these two micro-contexts, the director convinces us of the heart-melting experience of Najeeb’s existence beyond words.

Going back to Blessy films and his repertoire as a whole, one cannot escape the observation held by large segments of viewers that these are a sort of a laboratory of subtle human emotions. Goat Life is yet another stark example of this. It also has to be mentioned that unlike the novel, the film doesn’t present a religious point of view or it does not visualise the situation from that perspective.

All the characters in Goat Life exist as prototypes of human good and bad. In this context, it is also difficult to understand why and how the film was banned in the Gulf countries. Najeeb’s master, or Arbab, is not his real sponsor in the movie Goat Life. On the contrary, the course of this film is indirectly controlled and determined by the fact that it is a swindler Arab who deceives and exploits two Malayali youngsters who have no knowledge of the language. It is an unforgettable final scene in the movie when Najeeb bursts into tears with the realisation that he was living a life destined for someone else. There is no scope here to generalise that all sponsors are thieves or that all of them are saints. Indeed the fact remains, that the Gulf region is a place of employment for many expatriates. In direct contrast to Najeeb’s Arbab Arab, there is also the kind Arab who takes him from the road in a car and leads him into the city…!

In any case, the film ‘Goat Life’ clearly reveals Blessy’s phenomenal 16 year long struggle after “Kali Mannu”, his last film and the nurturing and emergence of a silent creativity through these struggles. In many ways, Goat Life is not merely the depiction of Najeeb’s survival story. It is also a marker of the artistic survival of filmmaker Blessy. Because what we see in Goat Life is the completion of his own journey towards fulfilling a dream, overcoming tough obstacles, without getting tired and of course without giving up.