A Canadian Journalist Remembers GN Saibaba

Canadian journalist and broadcaster Gurpreet Singh had a long association with GN Saibaba, the academic-activist who passed away recently on account of health issues, which developed severe complications during his long incarceration. Here, Singh presents some vignettes of the conversations he had with Saibaba and his family as well as the perspectives that these interactions imbued in him.

The passing away of the inspiring teacher and activist GN Saibaba is a personal loss for me. I am sure hundreds of others who had occasion to spent time with him would feel the same. I had got an opportunity to meet and talk to him in 2015 when he was on medical bail and was getting treatment in a Delhi hospital.

I was visiting India back then with my family. I went to see him to listen to his story first hand. I was indeed indignant seeing the manner in which the government was treating him. I saw myself repeatedly asking the question as to what danger a wheelchair bound man can pose to the mighty Indian state.

On that occasion, Saibaba spent several hours talking to me. That long conversation had a huge impact on me. He spoke like a teacher calmly and steadily. There was no bitterness in his demeanour. He explained not just what happened to him, but the whole scenario behind the extra judicial and extra constitutional witch hunt carried out by the government against groups and individuals, who were fighting vested interests. His narrations were so clear and had such a lasting effect that I do not get surprised anymore by the interminable news stories that keep coming out about the harassment and intimidation of political activists.

Saibaba told me that he was being made to pay the price for challenging the status quo and the political leadership of the country. He made me understand that it is rather easy for anyone to get bail if they are involved in purely illegal and criminal activity, whereas anyone involved in activism is playing with fire.

The criminals do not necessarily work to change the system, but rather take advantage of it to thrive, while political activism is all about striving to bring a change. He also narrated as to how criminals were being patronised in jails. One stream of his narration was about the painful experiences that the prisoners coming from the poor and marginalised sections of the society were made to undergo. He added that those from the minority communities, especially Muslims, bore the brunt of the extreme harassment in jails.

After we finished, I took several pictures of Saibaba and left with a promise to stay in touch. Once back in Canada, I used to speak with him over the phone for radio interviews. Each conversation with him was so hugely enlightening that I often felt I had become his student.

Then we began receiving reports that the right wing Hindu groups were not letting him restart his job as an educator citing criminal charges against him. When he went back to the jail, he was removed from his job and was never reinstated, even after his acquittal.

During his absence, I interviewed his wife Vasantha several times about his condition inside the jail, where he faced many hardships. The most difficult period was when Saibaba’s mother was battling cancer. Her hands were full with homely responsibilities of taking care of their daughter and the mother-in-law and dealing with legal fights to get her husband released.

Until recently, after his release, he was in touch with me and I did at least three long interviews, one of which was about a memorial event he organised for his deceased mother to bring some kind of closure.

Early this year, he was acquitted after the case was reopened following efforts of his legal team. It’s a separate matter that Surinder Gadling, one of his lawyers was also arrested and remains locked up in another infamous case under which many scholars and activists were booked from all over India.

When Saibaba finally got released from jail we all felt relieved, but this happiness was short-lived as he passed away because of his deteriorating health. Undoubtedly, October 12, 2024 will go down as another black day in the history of the world’s so-called largest democracy. Saibaba’s incarceration and his untimely death were indeed the result of prolonged institutional harassment. In other words, Saibaba’s death can only be termed as institutional murder.

He was first arrested in 2014 and thrown behind bars after being branded a Maoist sympathiser. His only crime was that he questioned power and stood up for the Adivasis or the indigenous peoples of India who were being forcibly evicted from the traditional lands by the extraction industry, which has a strong backing of the Indian ruling elite.

Since Maoist insurgents are active in the Adivasi areas, the government often try to suppress any voice of dissent by dubbing it as seditious Left Wing Extremism.

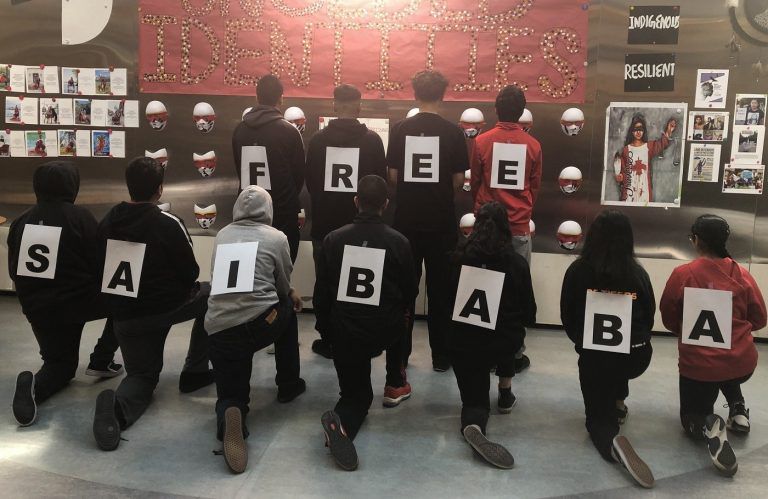

His arrest was followed by protests across the globe, including some in Canada. I also participated in a few of them. At stake was not only his right to free expression, but also his health as he suffered multiple ailments.

He got bail on medical grounds in 2015, but he was sent back to the jail to face trial and was subsequently convicted. Even as his health condition got worse in jail, he wasn’t getting proper attention or treatment. Even the UN had asked for his release, but the Indian establishment remained adamant and did not give him any amnesty.

The level of persecution was such that even when his mother was dying of cancer, he wasn’t given parole to see her for one last time. He was also denied the right to attend her last rites

Indeed, his death has come as a blow to those who have been raising their voices all these years for his freedom. Among them were the representatives of the Canadian Sikh community who signed petitions asking their government to intervene to press upon India to let him go. One of them was Hardeep Singh Nijjar, the Gurdwara leader who was assassinated in June last year allegedly at the behest of the Indian agents, who were apparently acting against his support for a separate Khalistan, carved out of India.

In spite of these efforts from social groups and individuals, the Canadian government that claims to be a champion of human rights in the world remained indifferent to the situation of Saibaba. Except for a few politicians and social justice activists, the elected officials of Indian origin and prominent political parties of Canada mostly looked away. The so-called disability rights’ advocates and the British Columbia (BC) Teachers Federation refused to make any statement.

It is interesting to note that Canadian politicians have been very vocal against any persecution of dissidents in China, Russia or Iran, but they would not touch the issue of a scholar who was ninety percent disabled. An online petition moved by a group of socially concerned people, of which I was also a part, advocating for the Nobel Prize to Saibaba did not go anywhere either, as western democracies have their own priorities.

Several educators in Canada did however initiate letter writing campaigns and classroom presentations to raise awareness about the situation of Saibaba. Following his death a vigil night and protest was organised in Surrey, British Columbia on Sunday, October 13. The speakers at the event unanimously held the Indian government responsible for the circumstances leading to his demise and chanted “Long Live Sababa” slogans.

During the last few months, Saibaba was looking for an accommodation as he feared that he could be evicted from his place of stay on account of the intense pressure from the government and social stigma attached to his name. He was looking for a ground floor house which should be both accessible and reasonably priced. I had persuaded a dear friend in Delhi to look after this. Even as we were regularly corresponding about it, he was hospitalised and breathed his last.

His words about how the Indian state patronised criminals, even while persecuting activists proved to be prophetic in his own death. Saibaba knew exactly why he had to suffer and chose to remain committed to his principles, even though he could have easily given up to live a comfortable life like many other armchair revolutionaries. But he was a living martyr, who refused to make any compromise in the face of barbarity.

Saibaba may have left us physically, but his legacy will remain alive through hundreds of people like me, who got enough political education from him to carry forward his mission for a just world.