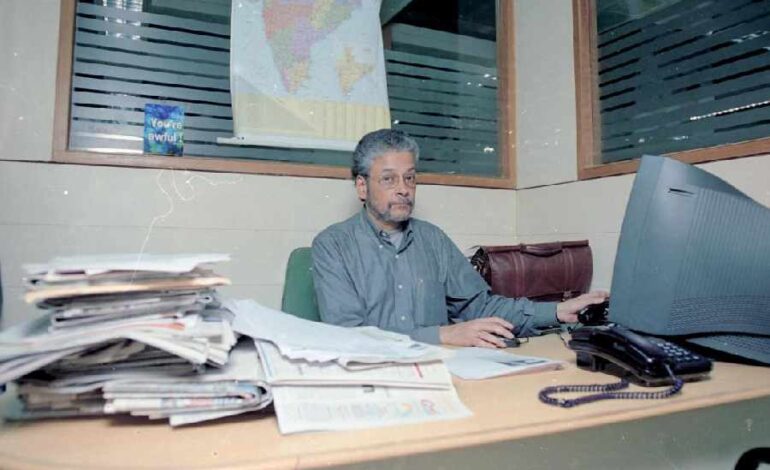

Some leaders command with authority; others inspire with presence. Deepayan Chatterjee belonged to the latter category. He didn’t raise his voice, he didn’t need to. A single glance, a softly spoken name, or a pause before delivering his verdict carried more weight than a thunderous reprimand. It wasn’t fear he commanded, but something far more unsettling, an unspoken challenge. Were you prepared? Had you thought beyond the obvious? Had you, in his way of thinking, “earned the ink” you spilled?

Deepayan Chatterjee didn’t just edit stories; he dissected them, tested their bones, and rewrote their fate. He was the unseen force behind a newspaper that didn’t just report history—it nudged it forward. Some editors refine words. He set them ablaze. And if you stood too close, you either burned—or learned.

“Kumar…”

The call from across the glasswall of his cabin was never a stentorian alert, not an authoritative command either, yet it used to freeze my nerves. It was not the fear of his wrath over my blunders but an instinctive reaction, perhaps the same jolt the Parker Solar Probe must have felt when it ventured too close to the sun. A moment later, I would stand in front of one of the finest editors I have ever worked under.

Deepayan Chatterjee was the faceless brain behind the making of the most iconic product of maverick journalism in India. Pardon me for not using the word rebellious despite its best-fit credentials.

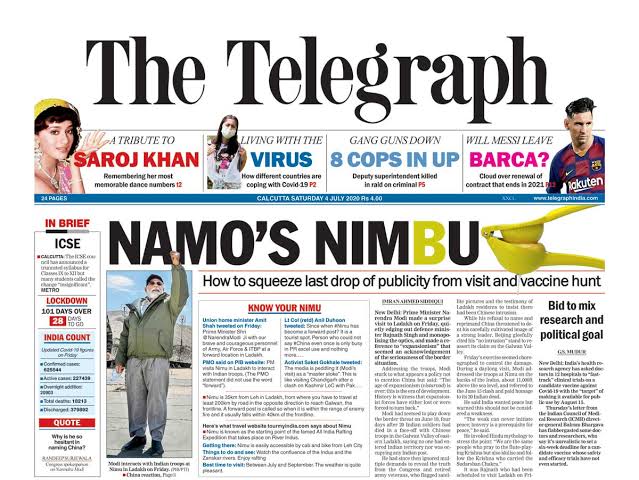

‘Defy Bandh’, screamed The Telegraph Page 01 lead headline in bold and all caps, when the ruling party and the opposition were both locked in a race in calling strikes. Those two words not just reflected the sheer disgust of people, but gave them the trigger to revolt. I knew the German phrase vox populi (voice of the people) but didn’t know of its might until I saw how the city shrugged off the strikers the next morning.

I witnessed how impeccably The Telegraph under Deepayan Chatterjee echoed the simmering discontent among the people in the sundown days of the red in Bengal. No other frontline newspaper in the country could reach that close to a neutral stand as TT did in those days of intense political turmoil. What intrigues me more even today is his unique ability to stand out in terms of content. Barring the days of major developments like the Boxing Day tsunami or the Samjhauta Express blast or the Nandigram massacre, TT would always come up with something unique and unpredictable on its page one.

Deepayanda, as we called him, not only read between the lines, he understood the spaces between them. He ruled the reader psyche with his choice of news and uncompromised ethics by never setting examples of extraneous journalism or yellow journalism. I always felt he was far ahead of his time.

I am not a Telegraph veteran like R Rajagopal, who had to handle this absolute misfit in his newsroom of brilliant junior editors, or Harshita Kalyan, who had to cover up for my countless mistakes, or Ananda Kamal Sen, my mentor to whom I would remain indebted for every word I write. My life in TT ended in little over three years. But those three years made me what I am today and what I would ever achieve.

If The Telegraph under Deepayan Chatterjee made me more reliable with copies, then it also left me less adaptable to the evolving trends of on-the-go English in Indian journalism. There was nothing ‘loosely said’ in his craft. ‘Guv’ never came up as a quick-fix for governor in headlines, neither ‘co’ replaced a company, nor did ‘biz’ stand up for business. “It takes almost the same time to give the headline as it takes to sub the copy.” I heard him saying this in the newsroom so many times. The words resonate louder when I see today’s self-proclaimed and self-contained ‘editors’ at work.

Will there be a hyphen between the two words in the middle of the fourth line of the fifth para in the second leg of the three-column, double-deck story below the fold and above the anchor on Page 6? He would look into every eye in the room, as we gathered around him right outside the editor’s cabin. Deepayan Chatterjee was perfection personified.

Some twenty years back, deadlines were less strict, turf war was less simmering, and readership was more dedicated, as smartphones were less smarter. But speed was never a cost his perfection had to bear. Fairly new in the trade, I would quietly observe his Z-reading of the page, scaled down to the A4 size in print, yet done in minutes. Even the tiniest error wouldn’t escape his eye.

In the first few days of editing and rewriting stories, the printouts of my edited copies would seem like porcupines on the prowl with their spines fanning out in all directions. That’s how Deepeyanda would spot and mark the errors in prints. There were grammatical errors that never caught my eye. There were argumentative errors that never occurred to me, there were factual errors that I never bothered to verify. In short, errors of all sorts that I had been blind to. As days passed and I struggled to improve myself, the porcupine calmed down slowly. But my aim for a spotless printout from Deepayanda was no less than a run for the Pulitzer.

My time in TT was too short to learn the most out of him, but he taught me one of the biggest lessons of my life in journalism. He would often say, “A good sub (a Fourth Estate jargon for a sub-editor, the entry-level position on the news desk) knows what to change, but an excellent sub knows what not to change.” His rationale came as a superlative to my malady of monologophobia in headlines.

If Deepayan Chatterjee, the editor, was taller than his stately appearance, then Deepayanda, the individual was a towering personality that created deference and distance at the same time. Perhaps, as a lesser mortal, I feared being burnt like Icarus by flying too close to the sun.

“Put that down, or you’ll burn your fingers.” I was so startled by his words that the book almost fell from my hand. I was trying to understand what The Economist Style Guide was all about. I had picked it up from the style books piled up on the adjoining desk of a senior editor who was tasked to create one for The Telegraph. I was too naive to grasp it then, but Deepayanda’s barbed remark was no dismissal, it was a challenge. A nudge to push deeper, to learn how the world’s most respected newsrooms sharpened their stories.

Deepayanda had his own way of grooming his juniors, but it was not merely about delivering the finest cerebral fodder to the reader, it was as much about defenestrating the boastfulness to emerge as a more refined individual. I remember the evening when he hailed a young reporter for getting a scoop from the bereaved family of a political leader who had passed away hours before. But everything fizzled out as soon as Deepayanda came to know how the reporter had leveraged the brand and showed his arrogance in pulling off the job. “You’re a human being first. Then a journalist. And, after that, you’re a Telegraph reporter,” he said, “You failed in the first level itself.” The editor spiked the scoop that day.

To me, Deepayan Chatterjee was an eclectic mix of fine sense of humour, admirable erudition, and astounding insight into almost everything. If his ghost stories kept us captivated after the edition in the thick of the night, then Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’s sarod played on his tiny speakers from his iPod helped us settle down in the evening hours of rush. If his contrarian habits made me intrigued, then his ability to strike a balance left me awed, every day.

Twenty-five years have passed since I joined the trade without being professionally educated or trained. I have scaled a height that an ‘accidental journalist’ like me, whose every evening at TT would begin with bringing tea for the entire nation desk, wouldn’t even imagine in his wildest dream. But I still can’t defy the man’s advice on my first day at The Telegraph: “Read one story each from The New York Times and The Economist every day if you want to be here and learn how to edit copies.” I don’t know how much I could master the craft as a cerebrally inferior member of Deepayan Chatterjee’s newsroom, but that’s where I saw the sun and soaked up the heat as much as I could to keep moving.