There was much debate during the course of the recently concluded Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, about the quality of the water at the Sangam, where crores of devotees thronged to take the holy dip. While the National Green Tribunal (NGT) stated that the water was contaminated and unfit for bathing and drinking, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath castigated NGT data as false propaganda.

Most people assume that flowing rivers are inherently clean water sources, impervious to pollution. While this belief is historically rooted—human civilizations have indeed flourished near freshwater sources, particularly rivers and lakes—it is important to acknowledge the changing contexts in which these water bodies exist.

Reliable water access has always been vital for survival, supporting agriculture, drinking water, sanitation, and transportation. These elements have played crucial roles in the establishment and development of civilizations.

This historical reliance on rivers is evident in the locations of many ancient settlements. For example, ancient Egypt thrived along the Nile, Mesopotamia was nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates, the Indus Valley Civilization developed around the Indus, and ancient China flourished along the Yellow River.

However, industrialisation and rapid population growth have drastically altered human interactions with rivers. Many rivers, once life-sustaining, have become degraded ecosystems struggling to support aquatic life.

A river is considered “dead” when its water quality deteriorates due to pollution. This pollution primarily results from human activities such as industrial wastewater discharge, untreated sewage release, and excessive agricultural runoff rich in nitrogen and phosphorus.

These nutrients trigger algal blooms, which, upon decomposition, deplete dissolved oxygen levels, creating conditions unsuitable for aquatic life.

A river becomes functionally dead when it can no longer support aquatic organisms due to critically low oxygen levels. Such conditions hinder the survival of fish and aquatic plants, making the river ecologically ineffective. Additionally, pollution renders the water unsafe for drinking, bathing, and irrigation.

Contaminated water becomes a vector for waterborne diseases and a breeding ground for antibiotic-resistant superbugs. The decomposition of organic matter further degrades water quality, causing unpleasant odors and worsening environmental decline.

In the case of the river “Ganga,” empirical evidence highlights alarming pollution levels, primarily driven by rapid urbanization, agricultural expansion, and industrialization in recent decades. Excessive water extraction for agriculture and other uses, coupled with the construction of barrages and dams, has disrupted the river’s natural hydrology.

The discharge of untreated sewage and industrial effluents has severely compromised water quality, contributing to widespread waterborne diseases that claim thousands of lives each year. This pollution has also led to a drastic decline in dolphin populations, plummeting from tens of thousands to just a few hundred.

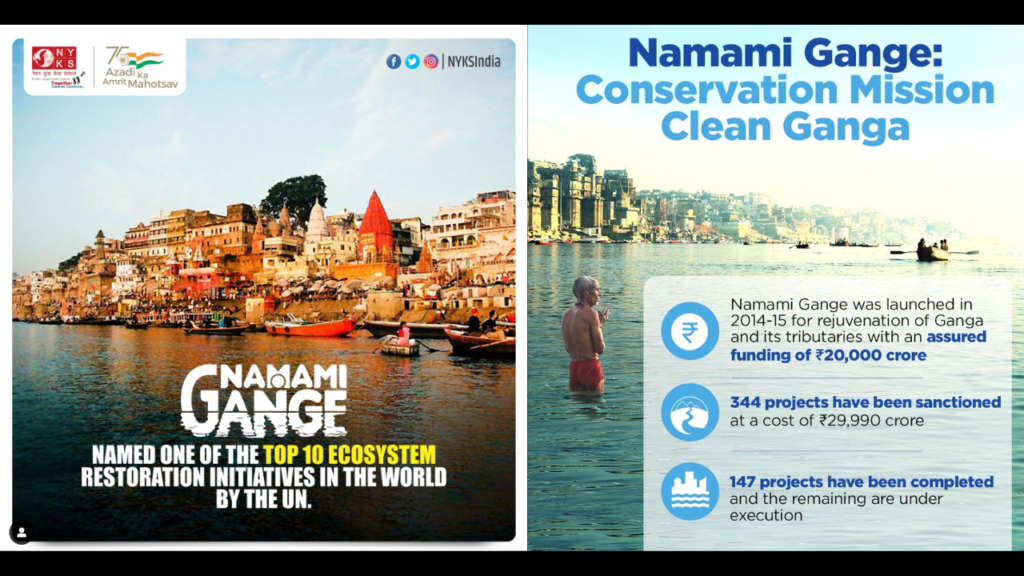

In response, the Indian government launched the Namami Gange program in 2014 with an initial investment of $4 billion. This initiative aims to reduce the inflow of untreated sewage and industrial waste into the Ganges. However, a critical question remains: Are these efforts effective? The challenge is immense, given that the municipalities along the Ganges generate an astonishing 300 billion liters of sewage daily.

This article was also published on Punjab Today News and can be read here.