Joe Sacco’s Human Lens on War and Suffering: Palestine and Beyond

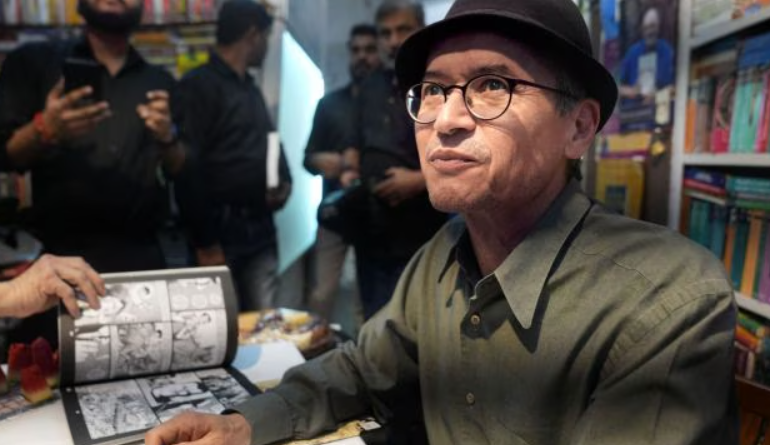

It was exactly a month ago, on November 14, 2024, that the legendary comics journalist, cartoonist and author Joe Sacco came to New Delhi’s Jawahar Bhawan for an interaction. On that evening, the auditorium at Jawahar Bhawan bore witness to one of the most profound exchanges on conflict, journalism, and the ethical dilemmas of reporting violence. This happened as Joe Sacco sat down with Seema Chishti, Editor of The Wire. Organized by Nehru Dialogues, the event attracted a diverse audience eager to engage with Sacco’s pioneering approach to storytelling, which has redefined the boundaries of reportage through the medium of comics.

Listen to the conversation between Seema Chishti, Editor of The Wire and Joe Sacco below:

For over three decades, Sacco’s work has chronicled some of the world’s most intractable conflicts, from the Israeli-Palestinian struggle to the war in Bosnia. His blend of journalism and illustration has illuminated the human cost of political turmoil, offering nuanced insights often missing in mainstream media. In this conversation, Sacco reflected on his unique craft, the ethical dilemmas of journalism, and the challenges of telling stories in a polarized and technologically complex world.

One of the first questions posed by Chishti was about Sacco’s self-identification. “If woken up at 3 a.m. and asked to describe your work, what would you say?” she asked. Sacco, with characteristic wit, responded, “First, I’d be pissed off that someone woke me at 3 a.m.” On a more serious note, he described himself as a cartoonist, explaining that his artistic impulses came before his journalistic ones.

Initially drawn to comics for their humor and creativity, Sacco’s trajectory shifted when he began using the medium to document his travels and explore political issues. This blend of the personal and the political emerged organically, as he recounted: “There was no theory behind it. I just went, asked questions, and drew what I saw.”

The medium of comics journalism allows Sacco to bridge the gap between objective reporting and subjective experience. His decision to depict himself within his stories is a deliberate choice, signaling to readers that they are viewing events through the lens of a specific observer. This approach subverts the traditional ideal of journalistic objectivity, which Sacco criticizes as an unattainable and often misleading standard.

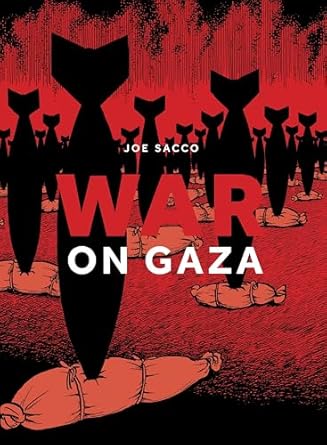

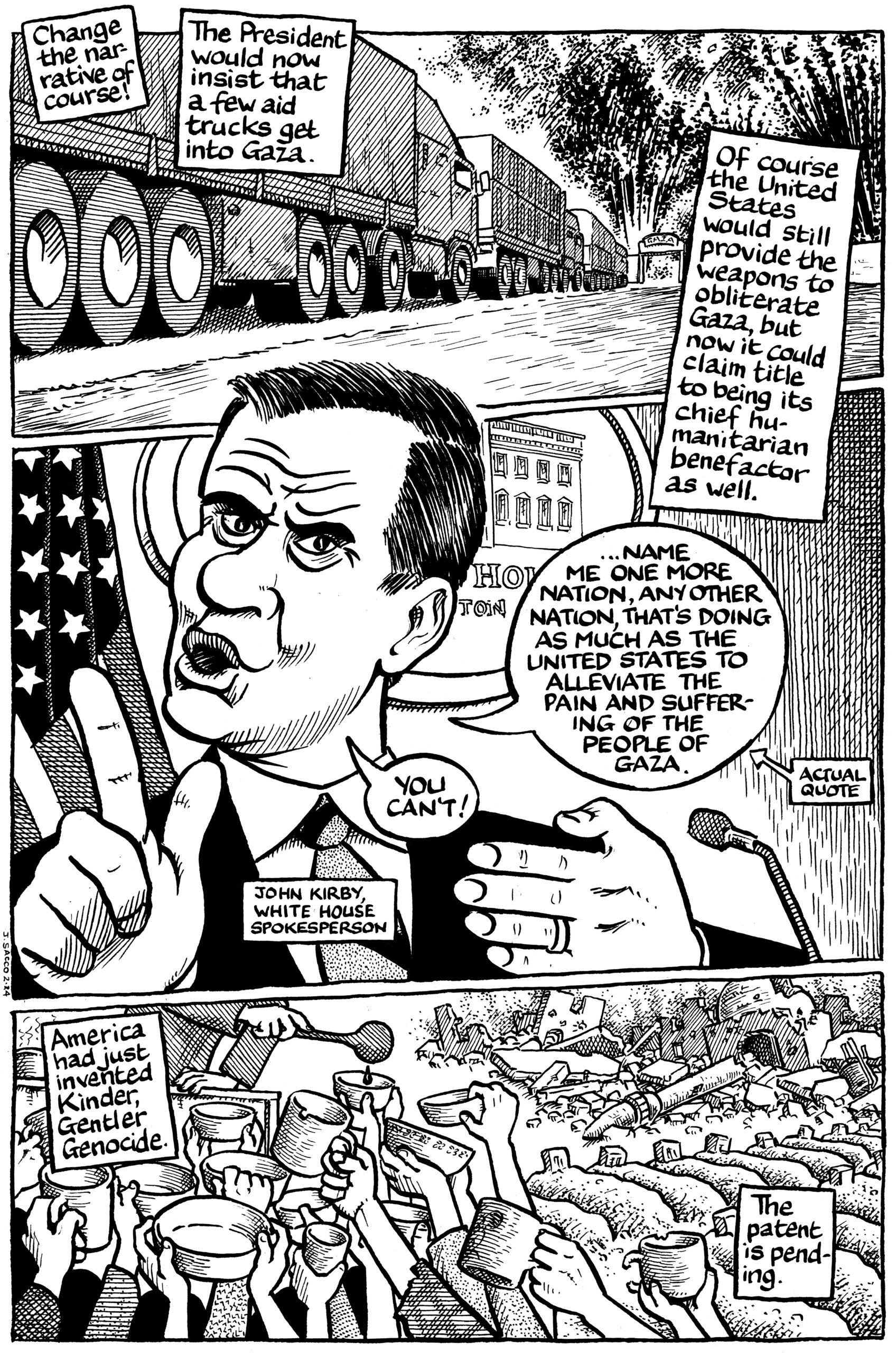

And indeed, the impact that his unique perspective and approach have left on the world as a whole, not just journalism, is to say the least “striking”. Consider this phenomenal observation he made about the current Gaza war that has gone on for more than a year now. Right from the beginning of the Israeli attacks on Gaza, marked specially by attacks on civilian targets including children, it was characterised as a “genocide”. On its part, Israel justified it as self defence.

As this debate continued and started dominating international headlines Joe Sacco struck with his pen. In one phrase, he exposed the fallacy of the Israeli argument. And that phrase: “genocidal self-defence”. It was both an indictment and an observation, a phrase that, in its paradox, captured the moral murkiness of Gaza’s decades-long plight.

Sacco’s work often delves into historical events that have been overshadowed by contemporary crises. In his acclaimed book Footnotes in Gaza, he investigated massacres in Rafah and Khan Yunis during the 1956 Suez Crisis, highlighting how these forgotten episodes continue to shape Palestinian identity. Chishti noted how Sacco’s insistence on revisiting the past sometimes clashed with his subjects’ priorities.

“Young Palestinians would ask, ‘Why are you talking about 1956 when houses are being bulldozed right now?’” Sacco explained. While he empathized with their concerns, he emphasized the importance of understanding history to grasp the roots of ongoing conflicts. “Events are continuous,” he observed. “For people living under constant siege, there’s no time to reflect on the past because the present is relentless.”

This commitment to historical context speaks to a larger critique of journalism’s often superficial treatment of complex issues. By focusing on personal narratives and the lived experiences of ordinary people, Sacco disrupts the dehumanizing tendency to reduce conflicts to statistics or abstract debates.

The conversation also addressed the dire challenges facing journalists today, particularly those working in conflict zones. Chishti brought up the alarming statistic of 137 journalists killed in Gaza, asking Sacco about the broader implications for press freedom. Sacco described the situation as unprecedented: “Journalists are not just caught in crossfire—they are being targeted. Their families are being targeted.”

Drawing from his own experience, Sacco recounted how American media shaped his early perceptions of Palestinians as “terrorists,” a narrative he later recognized as deeply flawed. “Balance isn’t about arithmetic mean; it’s about context,” he asserted, challenging journalists to prioritize truth over superficial neutrality.

As the discussion turned to the digital age, Sacco expressed concerns about the impact of technology on truth-telling. While new platforms offer opportunities for independent storytelling, they also amplify misinformation and enable powerful entities to manipulate narratives. Sacco singled out the erosion of trust in mainstream journalism, which he attributed to decades of misleading or incomplete coverage of issues like Gaza.

In this climate, Sacco believes that journalism must be reimagined as a vocation—a calling that demands integrity, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to uncovering the truth. “We’re being swamped by misinformation,” he acknowledged. “But we must keep the idea of real journalism alive.”

Chishti also highlighted Sacco’s lesser-known work in India, including projects on Dalit communities in Kushinagar and communal riots in Uttar Pradesh. Sacco’s investigation into Dalit welfare schemes revealed how systemic corruption undermines efforts to uplift marginalized groups. His forthcoming book, based on riots in Muzaffarnagar, examines the role of violence in electoral politics—a theme that resonates globally.

Sacco reflected on how these experiences deepened his understanding of narrative construction. “I wanted to see how people remember and justify their actions a year after a riot,” he said. This focus on storytelling, both personal and collective, aligns with his broader mission to explore how societies make sense of their histories and identities.

The event concluded with a poignant question from Chishti: “Is there hope for journalism in such a fractured world?” Sacco hesitated to use the word “hope,” but he found inspiration in the bravery of journalists working under unimaginable conditions. “They remind us what humans are capable of,” he said.

Sacco’s work, as Edward Said once noted, captures the “existential lived reality” of those trapped in cycles of dispossession and violence. Through his art, Sacco not only bears witness but also demands accountability, challenging readers to confront uncomfortable truths.

In an age of disinformation and polarization, his storytelling serves as a reminder that journalism is not just about reporting facts—it is about preserving humanity.