The Wonder Child of the World of Wonders

Writer and film critic GP Ramachandran presents a panoramic overview on Kamal Hassan’s creative journeys as the legendary cinema personality crosses the age of 70. This is an overview rich in detail and marked by nuanced studies of Kamal’s characters, capturing the stirrings of the actor’s unique contribution to cinema.

On November 7, 2024 Kamal Haasan completed the biblically ordained age of three score and ten. But the Seventy-year-old Kamal Haasan has completed an illustrious sixty-five years in the realm of film acting. This means that, though he has recently ventured into politics, there would be little left to say about the persona of Kamal Haasan beyond his legacy in cinema. And of course, this isn’t surprising; after all, for a star who has dedicated six and a half decades to acting, separating him from the world of cinema would be unthinkable. However, what truly stands out is also the fact that the story of South Indian cinema over the last 65 years simply cannot be told without significant references to Kamal Haasan. Kamal didn’t just walk alongside history; he often strode against its current, and at times, crafted history with a unique personal stamp.

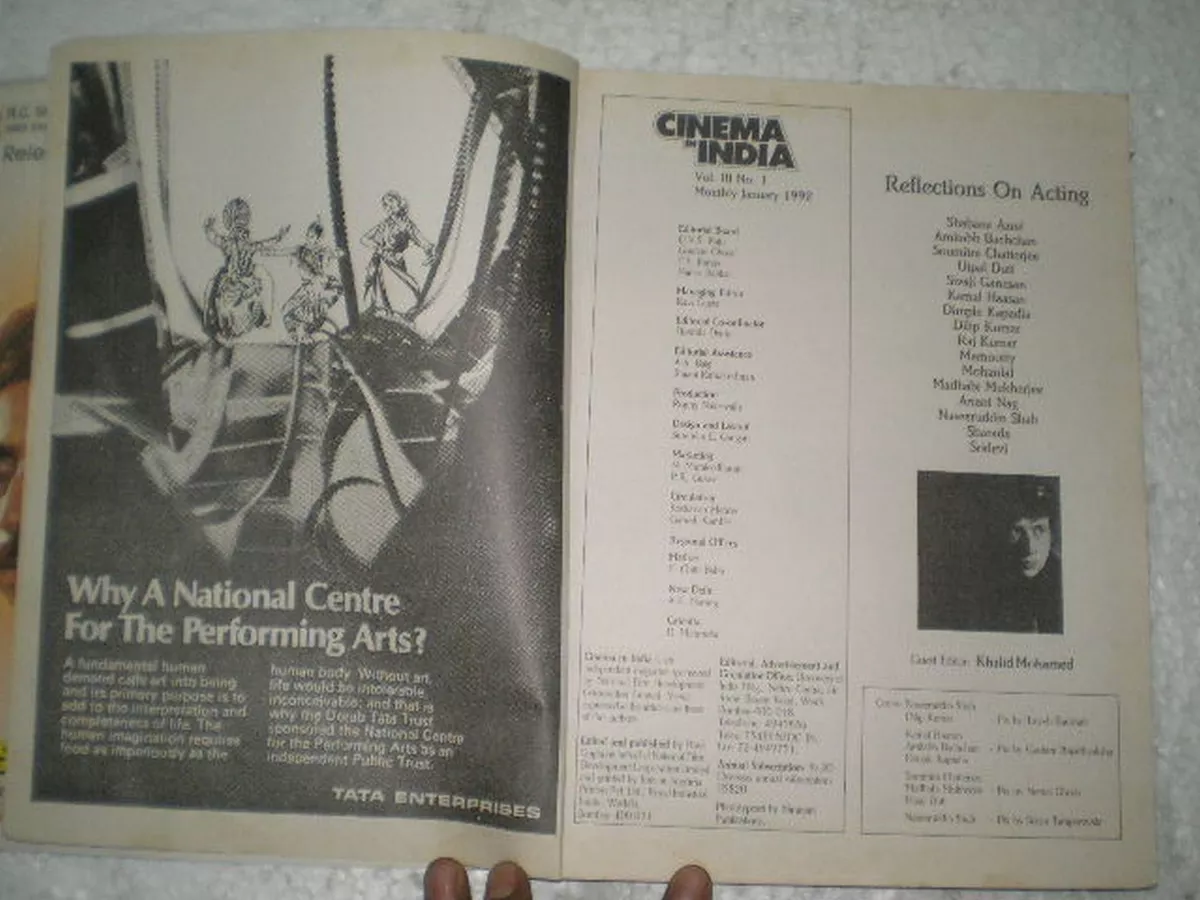

At the age of six, Kamal Haasan began his journey in cinema by acting in his first film, winning the National Award for Best Child Actor for his performance. He describes his connection with cinema in simple straightforward terms, “It’s not something I had to seek out in memory; I woke up to cinema” (from an interview with CNN IBN). When asked if he ever feared the intense lights needed for filming, he responded, “I would only feel unsettled if they were to go out someday” (Cinema in India Annual Edition, 1992). However, after shining as a child star, he spent a few years in the “dark,” away from the camera’s light.

The presence of contradictory forces and the convergence of inner and outer struggles characterise the inquiries into Kamal Haasan’s life and acting career. Born into a Brahmin family, Kamal lives as an atheist and a non-believer. While he proclaims himself a pacifist, he has no hesitation in entering into contracts with American and British corporations. Though regarded as a companion of Leftist politics—his sympathy for the Communist Party can be read through his film Anbe Sivam (Tamil/2003/Sundar C.)—Kamal initially took a ‘neutral’ stance against everyone in Tamil Nadu politics, a stance reminiscent of the Aam Aadmi Party( AAP) model, in the AAP’s early years. Yet later, he joined the Dravida Munnetra Kazhakam ( DMK) alliance, the very coalition he once opposed.

Despite a life marked by a couple of marriages and very many relationships, his role as a father takes precedence over the tangled issues these have caused in his personal life. As his daughter Shruti has stated on record, his role as father takes precedence over the role that her mother Sarika, herself a renowned actor of yesteryears, has in the lives of their children. Shruti’s statement does indeed upend traditional ideas of love, motherhood, and family.

Kamal, passionate about cinema, often disregards the basic principle that an actor should yield to the director, sometimes obstructing the completeness of the films he acts in. Yet he has never been willing to accept this fact. Consequently, Kamal has adopted an approach to acting that embraces projects far beyond the reach of a single lifetime, continuing his experiments by leaping into production, directing, music composition, songwriting, and singing.

Kamal was born into an Iyengar family as the son of D. Srinivasan, a criminal lawyer, and left school in the ninth grade to immerse himself in the world of cinema. His acting debut as a child was in Kalathur Kannamma (1960), directed by A. Bhimsingh, where he starred alongside Gemini Ganesan and Savitri. Kamal subsequently acted in five other films with superstars of that era, including Makkal Thilagam MGR and Nadigar Thilagam Sivaji Ganesan. Reflecting on this, Kamal recalls his father’s decision as a form of sacrifice made for art. “My father declared that, regardless of my two sons holding law degrees and my daughter earning a science degree, someone must be wholly dedicated to art. That was the most crucial and primary decision of my life,” he has stated. Srinivasan, a Gandhian and ardent secularist, reportedly gave his children the surname “Haasan” in honor of a Muslim friend.

Kamal’s elder brother Charuhasan, who also obtained a law degree, acted in films and won a National Award. Charuhasan’s daughter Suhasini and her husband, Mani Ratnam are well-known in cinema, adding to this illustrious family legacy.

However, this “Haasan” surname has sometimes brought Kamal complications. In the wake of the heightened fear of Muslims after 9/11, Kamal, during a tour in America, was subjected to a full body search. When this iconic actor—revered as “Universal Hero” in South Indian, and indeed Indian, cinema—was humiliated by American security forces, it was, in reality, an insult felt by all Indians. Notably, actors like Mammootty, Shah Rukh Khan, and even A.P.J. Abdul Kalam have faced similar indignities solely due to their Muslim identities.

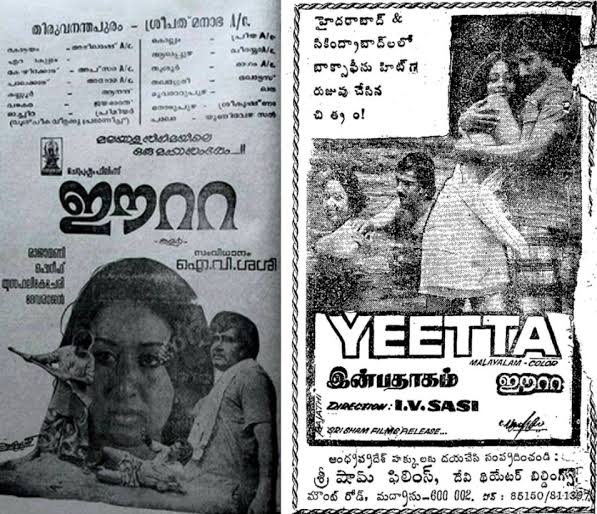

Kamal’s name is notable for more than just this singular characteristic. Initially, his name was written and pronounced as Kamalahasan. However, due to the feminine impression it gave off, he refined it to Kamal Haasan. From his youth, he emerged as an idol not only in South Indian cinema but also with films like Ek Duuje Ke Liye (Hindi/K. Balachander/1981). Yet, despite achieving fame, his body language often exuded an androgynous grace that unsettled his masculine aura. In films like Yeetta (Malayalam/I.V. Sasi/1978), Kamal’s characters utilised this delicate and subtle femininity to their advantage. The tension between being desired and adored by two women (portrayed by Sheela and Seema) was an ongoing motif within and around Kamal’s presence.

These women did not see in Ramu, Kamal’s character, the archetypal hero who dominated with raw masculinity. Due to the subtle hints of same-sex affection, Kamal’s roles, including his portrayal in Eeta, were considered as embodying “sissy” attributes, referring to effeminate male characters. It may well have been a fear of accusations of bisexual ambiguity that prompted him to drop the feminine touch from his name. It is clear that Kamal Haasan was susceptible to diverse mental states, a pattern evident throughout his cinematic journey.

His portrayal in explicit depictions and objectification of the female body, segmented into erotic components, alongside affirming old-fashioned beliefs about chastity, morality, marriage, and the symbolic thali (mangalsutra), marked many Tamil films of the era. It was nearly impossible for the average Tamil audience to easily embrace Kamal Haasan’s deviation from such dualistic journeys of Tamil cinema. This is why experimental films like Aalavandhan (Tamil/Suresh Krissna/2000), which dared to push the boundaries within mainstream cinema, were met with rejection by average viewers. Kamal’s lead roles in movies like Nayakan(Tamil/Mani Ratnam/1987) and Indian(Tamil/Shankar/1996) involved serial killings justified as responses to injustices endured in the past. The character’s vendetta in Aalavandhan could be rationalized in a similar vein. This eye-for-an-eye, blood-for-blood philosophy was symptomatic of madness and mental instability, with Aalavandhan attempting to present it as a profound commentary on hidden savagery. Despite having starred in numerous films that adhered to the conventional moral values celebrated in Tamil cinema, Kamal Haasan is best remembered for films like Aalavandhan, which provoked and challenged those very codes of ethics.

After finding success as a child artist, Kamal experienced a few years of relative obscurity before reclaiming his place in the acting world. His comeback was marked by the film Apoorva Raagangal (Tamil/K. Balachander/1975). This movie, which also marked Rajinikanth’s debut, was Kamal’s first major commercial success as an adult actor. The story revolves around Bhairavi (Srividya), a classical musician, who nurses Prasanna (Kamal), injured in a street fight, back to health. The warmth and honesty of the love that blooms between Bhairavi, a mother of a grown daughter, and the much younger Prasanna creates a narrative tension that challenged societal norms and stirred controversy. Meanwhile, Prasanna’s father proposes a marriage between him and a young girl, who turns out to be Bhairavi’s own daughter, Ranjini (Jayasudha). Kamal’s ability to imbue these unconventional stories with emotional depth was already evident in his early phase.

The film Moondru Mudichu (Three Knots/Tamil/K. Balachander/1976) showcased Rajinikanth in an impressive antagonist role and marked the beginning of many memorable collaborations between Kamaland Sridevi. In Bharathiraja’s directorial debut 16 Vayathinile (Tamil/1977), the trio appeared again in leading roles. This film, entirely shot outdoors, infused new vitality into the Tamil film industry at the time. Kamal portrayed Chappani, a simple-minded youth. The film centered around Mayil (Sridevi), a beautiful sixteen-year-old girl facing life’s harsh realities. In Sigappu Rojakkal (Red Roses/Tamil/1978), directed by Bharathiraja, Kamal played an antagonist with psychotic traits, while Sridevi played the heroine. Kamal’s character, Dileep, outwardly a businessman, harbored a dark secret – a proclivity for assaulting and murdering women.

Kamal’s journey to nationwide recognition expanded with the Telugu film Maro Charitra (Telugu/K. Balachander/1978) and its Hindi remake Ek Duuje Ke Liye (Hindi/K. Balachander/1981). In both films, Kamal played a Tamil youth in love with a girl who spoke a different language. In Maro Charitra, she spoke Telugu, while in Ek Duuje Ke Liye, she spoke Hindi. In both, Kamal acted as a Tamil youth living in another state.

These films placed Kamal as a cultural ambassador of Tamil identity before the entire nation. They subtly questioned the popular sentiment towards linguistic and cultural differences, mirroring the complexities of national integration and the prejudices surrounding it. The scenarios where characters who mock and treat those speaking the language of neighbouring States with disdain later receive applause were crafted to reflect the growing ‘ Manninte makkal’ ( sons of the soil) rhetoric in India and the intolerance that manifests from it.

In 1983, Kamal Haasan won his first National Film Award for Best Actor for his performance in Moondram Pirai (Tamil/Balu Mahendra/1983), where he played a school teacher caring for an amnesiac woman. His role resonated deeply for its tender and heartfelt execution. The Telugu filmsSagara Sangamam (1983, dubbed into Tamil as Salangai Oli) and Swathi Muthyam (1986, dubbed as Sippikkul Muthu), directed by K. Viswanath, turned into massive commercial successes across South India, solidifying Kamal’s pan-South Indian appeal.

Notably, Kamal’s early opportunities flourished in Malayalam cinema, where he featured in a variety of films: Kanyakumari, Vishnu Vijayam (1974), Njaan Ninne Premikkunnu, Thiruvonam, Mattoru Seetha, Raasaleela (1975), Agnipushpam, Appooppan, Samasya, Swimming Pool, Aruthu, Kuttavum Shikshayum, Ponni, Nee Ente Lahari (1976), Velankanni Mathavu, Sivathandavam, Aashirvadham, Madhuraswapnam, Sreedevi, Ashtamangalyam, Nirakudam, Ormakkal Marikkumo, Anandam Paramanandam, Sathyavan Savithri, and Aadyapaadam (1977). While many of these roles didn’t receive significant attention, films like Vishnu Vijayam, Madanotsavam (by N. Sankaran Nair), and Eeta (by I.V. Sasi) are remembered for various reasons.

As Kamal’s professional fees rose, Malayalam cinema struggled to afford him, leading industry analysts to speculate that his demand outpaced the regional budgets. Although other stars like Rajinikanth, Chiranjeevi, and later, Vikram and Vijay, achieved widespread fame by working across Tamil, Telugu, and other South Indian languages, none attained the comprehensive South Indian superstar status that Kamal Haasan achieved.

When compared to his contemporary, Rajinikanth, it can be observed that within Tamil Nadu, Kamal Haasan has always held the second position in terms of popularity and commercial success. While Tamils are often accused of being insular in their loyalties, it is noteworthy that Rajinikanth, hailing from Karnataka and whose native tongue is Marathi, was embraced and celebrated as their own hero. This is a topic that warrants deeper analysis. The Dravidian ideology, originally vibrant and anti-Brahminical in essence, was diluted over time by the likes of M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) and Jayalalithaa until its original sharpness was lost in a sea of moderation.

With the arrival of Jayalalithaa, the element of female dominance tinged with an excessive inclination toward power became evident. The backlash against this ascent sought a counter-symbol that could challenge the intertwined political and aesthetic elements of Brahmin dominance, female authority, and fair-skinned beauty. This search found its perfect answer in Rajinikanth. It is worth noting that, in post-Rajinikanth cinema, fair-skinned actors akin to Sivaji Ganesan and MGR were consistently relegated to secondary positions. Despite Kamal Haasan’s tenfold acting prowess, a vast range of roles, and undeniable glamour, he could never quite match Rajinikanth’s stature. This was because Kamal’s foray into experimental cinema diverted his career path, making their rivalry dissolve and rendering Kamal’s films beyond the realm of typical success-failure analysis. This dilution of competition was felt less sharply in later years. Even though actors who succeeded Rajinikanth lacked his acting talent, it was those with darker skin who claimed the top position. The success stories of Vijayakanth, Vijay, Prabhu Deva, Murali, Dhanush, Vijay Sethupathi, Kalabhavan Mani, Vishal, Jiiva, and Bharath highlight this aspect.

Following Punnagai Mannan (Tamil/K. Balachander/1986), where Kamal played dual roles including one reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin, Nayakan (Tamil/Mani Ratnam/1987) was released. Two prominent influences were attributed to this critically acclaimed film: imitation of the Hollywood classic ‘The Godfather’ series and the life story of Varadarajan Mudaliar, a notorious Mumbai underworld kingpin. However, when we look back 22 years later, it becomes clear that what set Nayakan apart was Kamal Haasan’s exceptional performance. His character, Velu Naicker, embodied themes of crime, the underworld, power, and the theatrical absurdities of law enforcement, all standard in cinema. Yet, the meticulous craftsmanship of Mani Ratnam, a new-age director with an acute eye for scene arrangement and narrative pace, made the film unforgettable in both popularity and legacy. Kamal’s facial expressions and physicality, especially in scenes like when he responds to his grandson’s question, “Are you a good man, Periyappa?” with “I don’t know,” were unparalleled and extraordinary. His performance in Nayakan earned him his second National Award for Best Actor. It’s worth noting that, through a blend of calculated and naturalistic acting, Kamal elevated the viewer’s admiration for both the underworld king and the world he inhabited. Films like Nayakan confirmed that Kamal Haasan is one of the greatest actors in Indian cinema.

Pushpak (released in Kannada and all South Indian languages as well as in Hindi/Shingetham Srinivasa Rao/1988), a unique silent film reminiscent of the silent film era, is one of the most notable achievements in Kamal’s film career. Although the narrative was based on the oft-repeated theme of a common man’s dream of becoming king for a day, it was the captivating use of visual language that defined this film. Pushpak, though devoid of dialogue, included background sounds that were cleverly utilized. The story featured an unemployed protagonist living in a run-down lodge adjacent to a seedy movie theater. At night, as he tries to sleep, the protagonist is subjected to the “dishoom dishoom” of the Hong Kong kung fu movie playing in the theater. When he unexpectedly finds himself with access to a five-star hotel room belonging to a wealthy drunkard, he relishes in the luxury only to find sleep elusive. The humor reaches its peak when, realizing the cause, he records the “dishoom dishoom” sound on a tape recorder, brings it to the hotel, and finally falls asleep with satisfaction. This humorous sequence underscores the vital importance of sound in both life and cinema. Pushpak is a testament to Kamal Haasan’s dedication to the history of cinema, showcasing his commitment in myriad ways.

Apoorva Sagodharargal (Tamil, later remade in Hindi as Appu Raja/Singeetam Srinivasa Rao/1989) was released in 1989. This film, a massive commercial hit, featured Kamal Haasan in three distinct roles, one of which was as a circus clown with dwarfism. Following the success of this role, Kamal embarked on a series of physical transformations and experiments. In films considered “art cinema” such as Guna (Tamil/ Santhanabharathi/ 1992), Avvai Shanmugi (Tamil, remade in Hindi as Chachi 420/K. S. Ravikumar/1996), Aalavandhan (Tamil/Suresh Krishna/2000), Anbe Sivam (Tamil/Sundar C./2003), and Dasavatharam (Tamil/K. S. Ravikumar/2008), Kamal showcased his dedication to experimenting with his physical appearance.

Kamal’s unique skill of playing multiple roles, which he seems to carry as a signature trait, has astonished audiences time and again. The most entertaining of these experiments, ranging from dual to as many as ten roles, was Michael Madana Kama Rajan (Tamil/Singeetam Srinivasa Rao/1990). In Kuruthipunal (Tamil/P. C. Sreeram/1995), Kamal successfully reimagined the complex narrative of Govind Nihalani’s Drohkaal, a tale woven with themes of terrorism, police integrity, familial obligations, and moral quandaries. However, when Kamal remade ‘A Wednesday’ as Unnaipol Oruvan (Tamil/Chakri Toleti/2009), it failed to garner significant attention. The minimalistic performances of Anupam Kher and Naseeruddin Shah in the original were hard to replicate, and Kamal and Mohanlal struggled to shed their star personas, contributing to the film’s lukewarm reception.

A brilliant example of how power and authoritarian tendencies creep into storytelling and command dominance is IndiaShankar/1996). The film dissects societal injustices, corruption, and the flaws of a decaying system, counterbalancing them with a vision of democratic liberation only to be overshadowed by a vigilante protagonist. The success of Indian, which celebrated such lone warriors, found echoes in the political campaigns of Narendra Modi and Raj Thackeray. Kamal’s performance in Indian earned him the National Film Award.

Hey Ram (Tamil and Hindi, directed by Kamal Haasan/2000) was notable not for its literal or symbolic interpretations but for how it unfolded. Viewers with sympathies toward Hindu fascism found the film resonated with their ideology. History attests that fascists derive joy from eliminating dissenters and orchestrating blood-soaked crusades. For a Hindu fundamentalist viewer, the lead character Saket Ram (played by Kamal Haasan), who openly embraces and acts on Hindu extremism, provided both direct and subtle gratification. Though the film concludes with Saket Ram undergoing a change of heart and embracing Gandhian philosophy, this may induce momentary disappointment for such a viewer, yet the ideological surge experienced up to that point remains impactful.

For those with alternative political and historical perspectives, the film also offered the possibility of witnessing a journey toward rediscovering Gandhi. Kamal’s assertion that ‘Hey Ram’ was meant to reveal both the beast and the peace-seeker residing within him may hold significance only from the perspective of those viewers inclined toward such introspection.

Virumaandi (Tamil/2004), directed by Kamal Haasan, was a poignant expression of the emotional argument against capital punishment. AngelaKothamuthu (portrayed by Rohini) embarks on a Ph.D. in civil law and joins a global campaign against the death penalty, driven by the searing grief of witnessing her father’s execution. Angel, as the film’s narrator, passionately argues that the complex workings of justice can lead to wrongful convictions, and if an innocent person faces capital punishment, it epitomizes inhumanity at its worst. The film portrays the emotionally charged events that led to the life imprisonment of Kothalathevar (Pasupathy) and the death sentence of Virumaandi (Kamal Haasan), encapsulating courtroom battles and the intense experiences within prison. Kamal Haasan pointed out that the film’s ‘A’ certificate was a testament to the flaws of censorship, arguing that society should reconsider whether censorship is still necessary, as its time had passed. His contention that censorship is an outdated tool of authoritarian control resonates with anyone possessing historical awareness, democratic values, and a taste for the arts. However, justifying the depiction of graphic and grotesque violence in ‘Virumaandi’ under the guise of anti-censorship seems contentious. While the technical finesse of scenes depicting severed limbs and close-up gore is evident, their believability may not be as consequential. Yet, the climactic scene of Kothalathevar being subdued with a finger pressed brutally into his neck, drawing blood, is undeniably unsettling and grotesque. Kamal Haasan himself has admitted that the hero he played in Indian (1996), who subdued the corrupt and anti-people figures by pressing on vital points, symbolized a justification for fascism. ‘Virumaandi’ also delves into caste pride, local identity, humanity’s inherent connection to the land and agriculture, and love that transcends social divides. These themes are elaborated upon with thoughtful and technical precision. Additionally, the ‘Rashomon’-style narrative, which juxtaposes the protagonist’s account with the antagonist’s version of the same events, adds dynamism and cinematic depth. However, while ‘Virumaandi’ proclaims its central anti-capital punishment message, the story’s blood-soaked violence and the binary of good versus evil seem to run counter to its declared moral standpoint.

Thevar Magan (1992), directed by Bharathan, glorified caste pride. Sivaji Ganesan plays Periya Thevar, the head of a village near Madurai. In the introductory shot that showcases his residence, the camera pans from a portrait of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to one of U. Muthuramalinga Thevar (a freedom fighter, Congress and Forward Bloc leader, three-time MP, and celebrated leader of the Thevar community). Periya Thevar proudly claims that his iconic moustache is a symbol of his heritage’s ferocity. Songs like ‘Potri Paadadi Penne, Thevar Kaaladi Manne’ (Worship and sing the praise of the earth under the Thevar’s feet) amplified this caste pride. Reports indicated that, following the release of the film, upper-caste violence against Dalits in the Tirunelveli region, which had been relatively dormant, resurged. In response to Thevar Magan’s glorification of caste dominance, Mari Selvaraj, then a college student in Tirunelveli, sharply criticized Kamal Haasan in a letter. This act of dissent marked the beginning of Mari Selvaraj’s journey as a filmmaker known for Dalit liberation-themed films. The echoes of caste pride resound in ‘Virumaandi’ as well.

In his grand cinematic experiment, Dasavatharam(Tamil/K. S. Ravikumar/2008), Kamal Haasan weaved together his evolving views on politics, history, mythology, ethics, and religion. The film intriguingly mixed temporal, historical, and political elements, from the Shaiva-Vaishnava conflict to a former CIA operative antagonist and a caricature of an American president reminiscent of the much-criticized George W. Bush. Despite being touted as a film filled with “miracles,” Dasavatharam faded into obscurity after a brief period of fascination.

In ‘Aalavandhan’, the main character Nandu, a mentally disturbed individual played by Kamal Haasan, recites a haunting line in a poem: “Kadavul Paathi Mirugam Paathi” (Half God, Half Beast). His self-justification is that while he appears beastly on the outside, within him resides divinity. Through this duality, Kamal Haasan attempts to highlight the blend of the animalistic and divine traits that intertwine not only in Nandu and his twin, Major Vijay, an army officer, but also in humanity at large. Kamal’s narratives often showcase this double-edged nature—employing violence and aggression in the pursuit of peace and non-violence. What is stated as the intention is one thing; what unfolds cinematically is often the stark opposite, embodying Kamal Haasan’s signature paradoxical storytelling.

The real reason behind the stalled production of the film about the warrior Marudhanayagam, executed by the British, remains a mystery. Historically, Marudhanayagam had converted to Islam and adopted the name Muhammad Yusuf Khan. The possibility that a despotic cultural or moral policing organization might have feared the exposure of this historical fact—a freedom fighter who willingly chose religious conversion in the 18th century and was then hanged by the British—remains a speculation. Yet, Kamal Haasan has so far refrained from openly discussing it. Could this be written off as another sign of his mental dilemmas?

Kamal Haasan, born a Hindu Brahmin but self-professedly devoid of caste and religion, has declared himself an atheist. He has also affirmed his belief with the proclamation ‘Anbe Sivam’—’Love is God’. From this, one thing is evident: for Kamal, cinema is his religion, caste, God, family, love, and passion. He embodies an innocent child who revels in the magic of cinema—created from a fusion of art, technology, capitalism, and wonder—living and breathing that wonder, performing, singing, dancing, battling, and occasionally falling headlong into it. Driven solely by an unmatched passion for cinema, Kamal Haasan embraces daring and extreme experiments while ensuring that his films reach a commercial zenith, even if it means facing failures more often than not.

Kamal Haasan does not subscribe to the notion that cinematic experiments are confined solely to art-house or purely aesthetic films. His strategic oscillation between mainstream appeal and experimentation defies conventional metrics of success and failure, proving that his ambitions transcend traditional benchmarks.

This article was originally published in Malayalam. Translated into English by Sania KJ, Journalism Intern at The AIDEM – Schumacher Centre media project in New Delhi.

Very Good Story

I’d have appreciated some critical views of Kamal’s career. His excessive and normalised Brahmanical discourse in his film is an example. At the same time, Hey Ram is a fantastic film (project).