Senior Journalist and author Nalin Verma’s fortnightly column in The AIDEM titled ‘Everything Under The Sun’ continues. This is the 7th article in the column.

Language is a reflection of our shared history, a melting pot of culture, and a battleground for identity. In India, this battleground has never been more fiercely contested than now. What happens when ordinary words are weaponized and languages, rich in diversity and heritage, are denigrated for political gain?

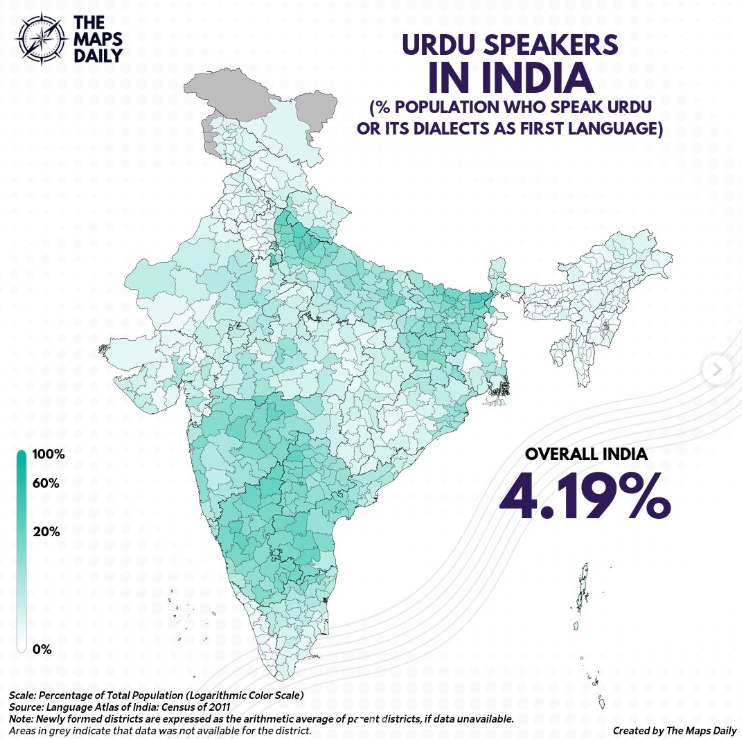

Under the garb of polarised speeches, like Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath’s vilification of Urdu, there lies a deeper, unsettling agenda— one that seeks to rewrite not just the languages we speak, but the very narrative of what it means to be Indian. From attempts to erase Urdu to attacking English, and even neglecting the endangered dialects that shaped Hindi itself, we are witnessing a systematic effort to dismantle the pluralism that forms the bedrock of this nation.

The question remains— can centuries of shared linguistic harmony be bulldozed so easily? This is not just about the words, this is about who controls it.

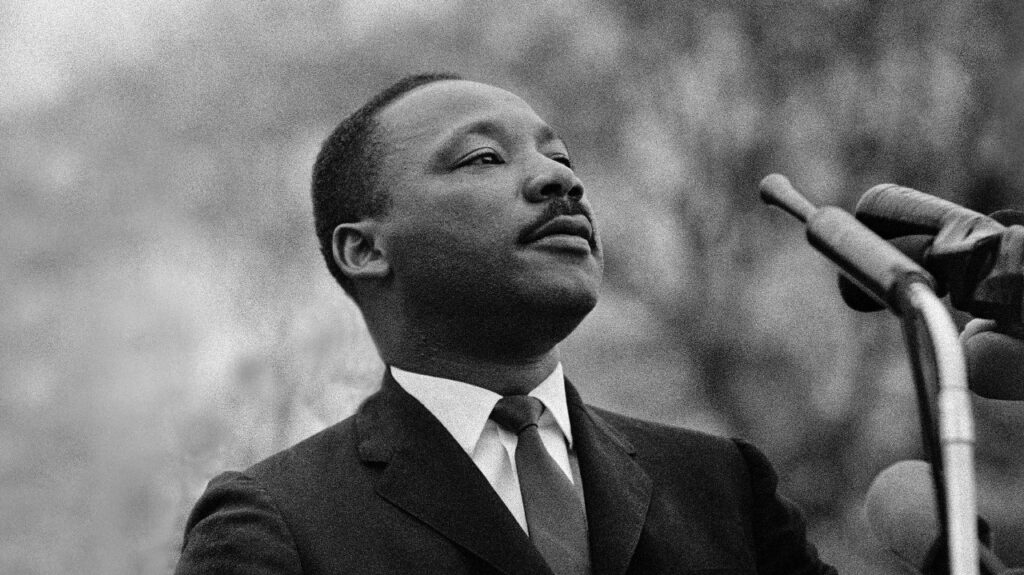

“Nothing in the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) [pictured above], political philosopher and civil rights activist, may have coined these words to describe the tormentors of human dignity in America during his era. But like Mahatma Gandhi, who became a metaphor for non-violence against colonisers, King Jr. too emerged as a voice against white supremacists everywhere.

Consider what Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath said in the Assembly: “Those leaders who plead for teaching children in Urdu want to make them maulvis and take the country on the path of Kathmulla,” in response to Samajwadi Party leader Mata Prasad Pandey’s demand for Urdu translation of House debates.

If anything, Adityanath’s venomous remarks reflect his deep-seated hatred for Muslims, which he habitually spews to polarize voters along communal lines. In doing so, he fits perfectly within Martin Luther King Jr.’s definition of “conscientious stupidity.”

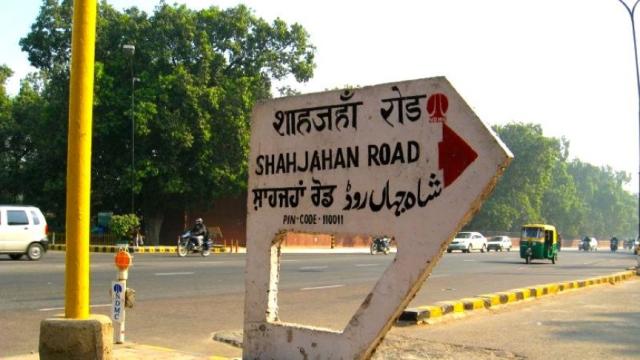

Separating Urdu from Hindi is like stripping colors from a rainbow. Adityanath may have performed jalabhishek (ritual bathing of Lord Rama’s statue with water) on the first anniversary of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya this January, but when thirsty, he likely asks for paani (water)—a word that also means ‘character,’ ‘reputation,’ and ‘honor,’ besides referring to drinking water and rain. He must be using kitaab (book) from Arabic and darwaza (door) from Persian—words deeply embedded in the everyday speech of the Hindi heartland.

The people of this region do not need scholarly research to appreciate the works of master storyteller Dhanpat Rai, alias Munshi Premchand, who wrote in both Urdu and Hindi, or Raghupati Sahay, alias Firaq Gorakhpuri, who wove magical verses in Urdu. Regardless of their religious identity, Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians use words like khana-pani (food and water), hisab-kitab (accounts), chadar (sheet), takiya (pillow), akhbar (newspaper), dua (prayer), salam (greeting), bandagi (devotion), ishq (love), mohabbat (affection), khushi (happiness), gham (sorrow), ansoo (tears), yaad (memory), naram (soft), garam (hot), bhai (brother), chacha (uncle), taaz (fresh), takhta (plank), chirag (lamp), and misaal (example). These words, originating from Arabic, Persian, and Romani, are an inseparable part of the spoken Hindi-Urdu continuum, used alike by both the unlettered peasantry and the educated elite. Attempting to separate Urdu from Hindi is akin to mutilating the voice of the people, a voice shaped by centuries of cognitive evolution.

Urdu is the ornament of Hindi, which itself draws nourishment from Awadhi, Brajbhasha, Kannauji, Bundeli, Marwari, Bhojpuri, Maithili, Magahi, Vajjika, Angika, Khari Boli, and numerous other languages and dialects spoken across Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, and Delhi.

By branding Urdu speakers as “Kathmulla,” Adityanath has laid bare his “dangerous” agenda, rooted in what Martin Luther King Jr. termed “sincere ignorance” and “conscientious stupidity.” In doing so, he seeks to erase the folklore, literature, and rich socio-cultural fabric that have united people of diverse castes, creeds, colors, and faiths for centuries.

But as the eminent stand-up comedian and five-time Grammy winner George Carlin (1937–2008) once said, “Never underestimate the power of stupid people in large numbers.” Adityanath stands at the forefront of this dangerously “large” crowd that dominates India’s power structures today. He is part of the larger Sangh Parivar—a conglomerate of zealots rooted in Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s vision of Hindutva, rewriting India’s historical, linguistic, and cultural landscape. They are bulldozing the very essence of India that is Bharat with impunity.

Adityanath’s bigotry and hatred toward Muslims are part of the tandav (destructive dance) that Hindutva extremists have unleashed on the streets with ferocity, under the patronage of those in power.

Hindi Chauvinism

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat, while addressing the Hindu Ekta Sammelan in Cherukolpuzha, Kerala, recently reignited the language debate by stating, “Hindus shouldn’t speak English… They should not speak videshi bhasha (foreign language) in their homes. They should use Hindi or whatever their matri-bhasha (mother tongue) is.”

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi countered Bhagwat’s statement by pointing out that “Several Sangh Parivar leaders have their children studying in English schools in foreign countries.” However, Rahul’s rebuttal to Bhagwat’s archaic advice is somewhat misplaced and lacks depth.

#WATCH | While interacting with students in Rae Bareli today, Congress MP Rahul Gandhi said, “People from BJP-RSS say that one should not learn the English language. Mohan Bhagwat says we should not speak in English. But the English language is a weapon, if you learn this… pic.twitter.com/VQEVJfEBSO

— ANI (@ANI) February 20, 2025

A more fitting challenge to Bhagwat would have been to ask him to provide Hindi equivalents for words like bus, train, tractor, tempo, school, class, tiffin, telephone, mobile phone, internet, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Wi-Fi, data, station, railway, shirt, pant, belt, cycle, motorcycle, car, taxi, copy, pencil, and rubber—words that have seamlessly integrated into everyday communication across the Hindi heartland and beyond.

Of course, English was introduced as the medium of instruction in secondary education by Lord William Bentinck in 1834–35, based on Thomas Babington Macaulay’s recommendations, to serve British colonial interests. However, nearly two centuries later—including 78 years of independent India—English has been thoroughly absorbed into daily life across the country, from north to south and east to west.

Setting rhetoric aside, the reality is that excluding English from Hindi—or any Indian language—would impoverish our languages and literature rather than enrich them.

Scholar-activist Yogendra Yadav, in his Deshkal column in The Indian Express, recently wrote: “This would be a test of our political class to take on the elephant in the room—the hegemony of English in our education system. It may be easier to resist a repressive and authoritarian state or stand up to an industrial-military complex than to break free of the dense web of power that is the rule of the English language.”

However, Yadav—a noted thinker influenced by the socialist philosophies of Ram Manohar Lohia and Kishan Patnaik—presents a contradictory argument. Is it truly easier to resist the “dense web” of repression and authoritarianism that the Sangh Parivar, under Narendra Modi’s leadership, has unleashed upon India’s minorities and marginalized communities simply by rejecting English? Is it really the dominance of the English language that empowers Hindutva radicals to systematically dismantle India’s secular ethos, cultural heritage, and constitutional values? Yadav’s bias against English stems from the narrow ideological lens through which North Indian Lohiaite socialists perceive Hindi.

Time to Protect Endangered Dialects

Kumaoni and Garhwali—languages spoken in Uttarakhand, a state carved out of Uttar Pradesh in 2000—are among UNESCO’s list of endangered languages. They are also among 13 endangered languages of Uttarakhand and part of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India’s list of 117 endangered languages across the country. Despite the fact that over 40% of Uttarakhand’s population speaks native languages or dialects, Hindi remains the state’s sole official language, with none of these indigenous languages included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

Mulayam Singh Yadav, a staunch proponent of Hindi, hailed from the Kannauj region of Uttar Pradesh. Ironically, the Kannauji dialect—along with Brajbhasha and Awadhi, which form the cultural backbone of Hindi—is now endangered, largely due to the overemphasis on standardised Hindi. It is reassuring to see that Mulayam’s son and Samajwadi Party chief, Akhilesh Yadav, has expressed concern about the decline of Kannauji.

1st & 2nd Most Spoken Languages of Uttarakhand State.

Note : The data has been prepared as per 2011 Government Census of India#Garhwali #Kumauni #Hindi #Punjabi #Urdu#language #languages #polyglot #maps #map #mapping #linguistics #linguist #polyglots #polyglotsofinstagram pic.twitter.com/aLShGxiwHt

— Know Your Roots (@knowyourroots_) February 28, 2021

Noted Hindi scholar Ramchandra Shukla, in his seminal work on the history of the Hindi language and literature, divided the evolution of Hindi into three phases—Aadi Kaal, Bhakti Kaal, and Aadhunik Kaal. He regarded Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas as the greatest work in Hindi literature. However, Ramcharitmanas is written in Awadhi. Similarly, Surdas’s verses and songs dedicated to Lord Krishna are in Brajbhasha.

The key takeaway here is that Hindi is not an independent language in itself; rather, it has evolved by assimilating various regional dialects along with Prakrit, Apabhramsha, and Pali, as well as Persian, Arabic, and now English.

If the 13th-century mystic Amir Khusro contributed to the evolution of Hindi by writing “Chaap tilak sab chhīnī re mose nainā milāike” (You’ve taken away my identity—prayer callus, zabiba, tilak, tika—and everything from me just by looking into my eyes), then contemporary writer Ruskin Bond has preserved cultural identity more than most, capturing the beauty of the hills, flowers, and people of Garhwal through his English writings, such as The Blue Umbrella and numerous other stories.

Currently, Yogendra Yadav and other proponents of Hindi are engaged in countering Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin’s refusal to introduce Hindi in the state’s school curriculum, opting instead for a two-language policy—Tamil, a classical language rich in literature, and English. However, rather than fighting over Hindi, it is far more urgent to unite in preserving the countless endangered dialects across India, from north to south and east to west, which define the country’s unique diversity.

Instead of confronting Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam speakers, scholars and political leaders in the Hindi heartland should heed the words of Naina Rawat, a young student who, through her dance and ballad performance on International Mother Language Day at Quantum University, Roorkee, on February 21, lamented the gradual extinction of her native language in Chamoli, Uttarakhand.

Precise on facts and superbly written . Vintage Nalin Verma ., thank you for this Sir

It is an analytical unbiased presentation. We should look for the harmony and not for the division. No language is rich without the words borrowed from other languages. Associating urdu with Kathmullapan is a pseudo association.