“Unfortunately, we, who learn in colleges, forget that India lives in her villages and not in her towns. India has 700,000 villages and you, who receive a liberal education, are expected to take that education or the fruits of that education to the villages. How will you infect the people of the villages with your scientific knowledge? Are you then learning science in terms of the villages and will you be so handy and so practical that the knowledge that you derive in a college so magnificently built – and I believe equally magnificently equipped – you will be able to use for the benefits of the villagers?” – {Speech in reply to students’ address, Trivandrum, March 13, 1925 in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 26, pp. 299-303}

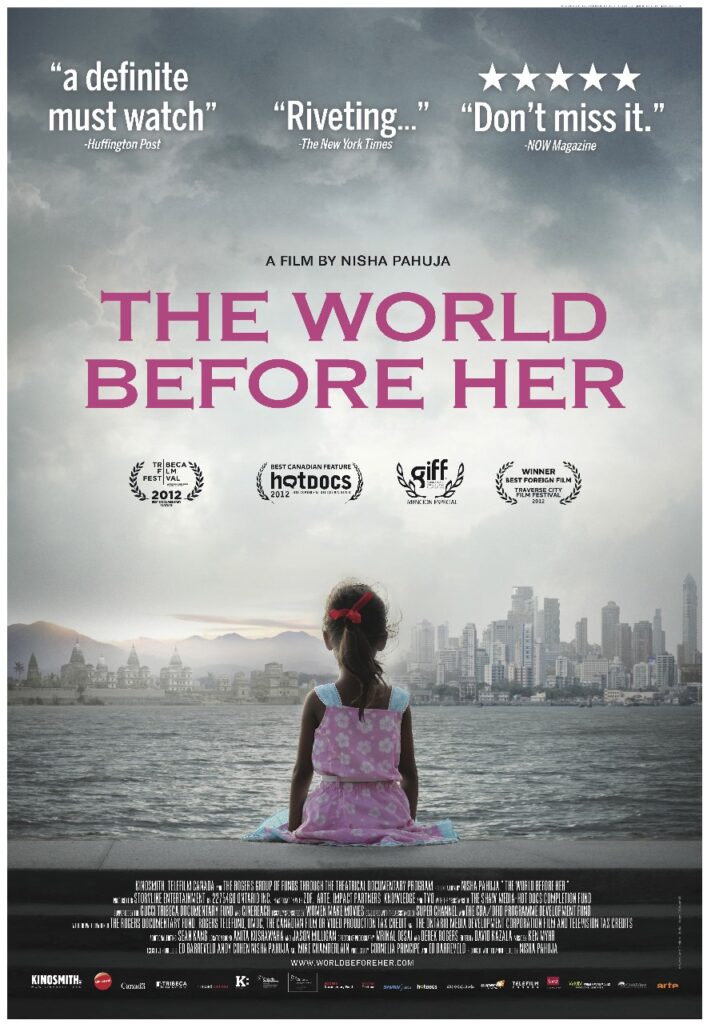

What would Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi have made of a society, which has turned its back so soon on his attempts to usher in a culture of progress, science, and tolerance in a fundamentally violent society where the lives of the traditionally disadvantaged castes were nasty, brutish and short? An extreme example is provided in Nisha Pahuja’s documentary The World Before Her, in which Prachi Trivedi, 24, a stocky Durga Vahini, women’s youth wing of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, activist who fiercely says: “Frankly, I hate Gandhi.” Probably his lifelong adherence to Jesus’s maxim of turning the other cheek would have made him accommodative of her antagonism also.

This culture of forgiving, which the Mahatma advocated made him a moral exemplar for statesmen and world leaders such as Rev. Martin Luther King, Nelson ‘Madiba’ Mandela, Rev. Desmond Tutu and Rev. Jesse Jackson. “Prior to reading Gandhi, I had concluded that the ethics of Jesus were only effective in individual relationships. The ‘turn the other cheek’ philosophy and the ‘love your enemies’ philosophy were only valid, I felt, when individuals were in conflict with other individuals; when racial groups and nations were in conflict, a more realistic approach seemed necessary.

But after reading Gandhi, I saw how utterly mistaken I was. Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale. Love for Gandhi was a potent instrument for social and collective transformation. It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking.” – Stride Toward Freedom {p.96-97}, Martin Luther King; who warmed to the Mahatma post-Montgomery.

Decades later, in an address at the unveiling of the Gandhi Memorial on June 6, 1993, in Pietermaritzburg, Mandela was to declare : “He negotiated in good faith and without bitterness. But when the oppressor reneged he returned to mass resistance. He combined negotiation and mass action and illustrated that the end result through either means was effective. Gandhi is most revered for his commitment to non-violence and the Congress Movement was strongly influenced by this Gandhian philosophy, it was a philosophy that achieved the mobilisation of millions of South Africans during the 1952 defiance campaign, which established the ANC as a mass based organisation. The ANC and its alliance partners worked jointly to protest the pass laws and the racist ideologies of the white political parties.”

In the domain of economics, where Gandhian views are considered antediluvian and Luddite, there is a necessary and differing Occidental academic opinion. Delivering the Gandhi Memorial Lecture at the Gandhian Institute of Studies at Varanasi in 1973, Dr. EF Schumacher, the humane socialist economist, narrated this story: “A German conductor was asked who he considered as the greatest of all composers. ‘Unquestionably Beethoven’ was his answer. He was then asked ‘Not even Mozart?’ He said ‘Forgive me. I thought you were referring to the others.’

Drawing a telling parallel Schumacher said the same initial question might be put to an economist as to who was the greatest. The reply invariably would be ‘Definitely Keynes.’ ‘Would you not even consider Gandhi?’ ‘Forgive me; I thought you were referring to the others.’”

And in the Orient, Masanobu Fukuoka, the Japanese author of One Straw Revolution, which inspired many to convert to Natural Farming too was inspired by Gandhi. In Fukuoka’s words: “I believe that Gandhi’s way, a methodless method, acting with a non-winning, non-opposing state of mind, is akin to natural farming. The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

Such striving for a life of ethical rectitude can be glimpsed from this episode from My Experiments with Truth. Gandhi mentions the bitter fight he had with Kasturba over her refusal to clean the latrine, wanting a ‘bhangi’ to do it instead. When Kasturba refused to give in, Gandhiji did the job himself. This brings to mind the anecdote of a chance visitor catching President Abraham Lincoln polishing his own shoes: “Mr. President, you are polishing shoes?” “Of course, I do my own,” answered Lincoln innocently, “So, whose do you polish?”

Mahatmaji’s culture of secularism needs special mention. The first principle of democratic secular humanism is its commitment to free inquiry, which opposes any tyranny over the mind of man, any efforts by ecclesiastical, political, ideological, or social institutions to shackle free thought. Free inquiry entails recognition of civil liberties as integral to its pursuit, that is, a free press, freedom of communication, the right to organise opposition parties, and freedom to cultivate and publish the fruits of scientific, philosophical, artistic, literary, moral and religious freedom.

Free inquiry requires that we tolerate diversity of opinion and that we respect the right of individuals to express their beliefs, however unpopular they may be, without social or legal prohibition or fear of sanctions. The guiding premise of those who believe in free inquiry is that truth is more likely to be discovered if the opportunity exists for the free exchange of opposing opinions; the process of interchange is frequently as important as the result. This applies not only to science and to everyday life, but to politics, economics, morality, and religion.

Because of their commitment to freedom, secular humanists believe in the principle of the separation of religion and state. The lessons of history are clear: wherever one religion or ideology is allowed dominant status, minority opinions are jeopardised. A pluralistic, open democratic society allows polyphony or multiplicity of voices. Compulsory religious oaths and prayers in public institutions {political or educational} are also a violation of the separation of powers principle.

A repeated usage of the term occurs early in Gandhi’s writings and speeches in 1933. Later, on January 27, 1935, Gandhi, addressing some members of the Central Legislature, said that “even if the whole body of Hindu opinion were to be against the removal of untouchability, still he would advise a secular legislature like the Assembly not to tolerate that attitude.” {Collected works}. On January 20, 1942 Gandhi remarked while discussing the Pakistan scheme: “What conflict of interest can there be between Hindus and Muslims in the matter of revenue, sanitation, police, justice, or the use of public conveniences? The difference can only be in religious usage and observance with which a secular state has no concern.”

In September 1946, Gandhi told a Christian missionary: “If I were a dictator, religion and state would be separate. I swear by my religion. I will die for it. But it is my personal affair. The state has nothing to do with it. The state would look after your secular welfare, health, communications, foreign relations, currency and so on, but not your or my religion. That is everybody’s personal concern!”

A part of his conversation with Rev. Kellas of the Scottish Church College, Calcutta, on August 16, 1947, was reported in Harijan thus: “Gandhiji expressed the opinion that the state should undoubtedly be secular. It could never promote denominational education out of public funds. Everyone living in it should be entitled to profess his religion without let or hindrance, so long as the citizen obeyed the common law of the land. There should be no interference with missionary effort, but no mission could enjoy the patronage of the state as it did during the foreign regime.” This was subsequently reflected in Articles 25, 26 and 27 of the Constitution.

Gandhi observed in a speech at Deshbandhu Park, Calcutta on August 22, 1947: “Religion was a personal matter and if we succeeded in confining it to the personal plane, all would be well in our political life… If officers of Government as well as members of the public undertook the responsibility and worked wholeheartedly for the creation of a secular state, we could build a new India that would be the glory of the world.”

On Guru Nanak’s birthday on Nov 28, 1947, Gandhi opposed any possibility of state funds being spent for the renovation of the Somnath temple. He reasoned thus: “After all, we have formed the Government for all. It is a ‘secular’ government, that is, it is not a theocratic government, rather, it does not belong to any particular religion. Hence it cannot spend money on the basis of communities.”

Six days before Gandhi was felled by a Chitpavan Brahmin, he presciently wrote: “A well-organised body of constructive workers will be needed. Their service to the people will be their sanction and the merit of their work will be their charter. The ministers will draw their inspiration from such a body which will advise and guide the secular government.”

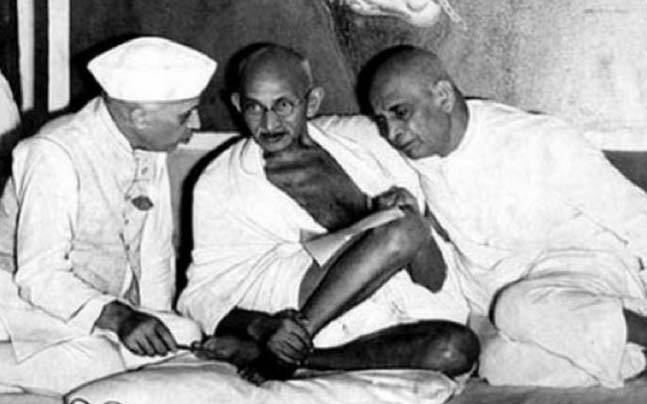

Both Gandhi and Nehru favoured territorial nationalism, clearly demarcating themselves from the Hindu Mahasabha, which would define nation or nationality on the basis of religion.

Perhaps Gandhi’s greatest achievement in the historic Non-cooperation movement of 1920-22 was the amazing participation of Muslims, which lent it an inclusive and mass character. This, in turn ensured communal harmony, rending to shreds the till then successful snare of the British in playing off the two communities against each other. In fact, so pronounced was Muslim support to the cause of the freedom struggle that history is our witness that in some places two-thirds of these arrested were from that community.

This remarkable spirit of the man who could bend the societal arc of his time to the moral compass of his conscience was best grasped by a little known Australian-born British classical scholar and public intellectual. “Persons in power,” Gilbert Murray prophetically wrote about Gandhi in the Hibbert Journal in 1918, “should be very careful how they deal with a man who cares nothing for sensual pleasure, nothing for riches, nothing for comfort or praise, or promotion, but is simply determined to do what he believes to be right. He is a dangerous and uncomfortable enemy, because his body which you can always conquer gives you so little purchase upon his soul.”

There is a reason for this reminder to ‘persons in power’. As per reports on December 25th at a function in Patna organised by a former Union minister in Modi’s cabinet folk singer Devi was stopped from singing Gandhi’s favourite Bhajan, ‘Raghupati raghav raja ram’, when she reached the stanza ‘Ishwar Allah tero naam’. She was allegedly forced to apologise by BJP workers at Bapu Sabhagar auditorium gathered to celebrate the 100th birth anniversary of former Prime Minister Vajpayee. Following the apology, it is further reported that the audience chanted “Jai Shri Ram” in full volume.

These bigoted hatemongers will yet come to realise that the syncretic teaching of Gandhi, mirroring the composite ethos of our accommodating shores, which still resonates in the hearts of his beloved daridra narayans and narayanis, will prevail forever. For the flame that was lit on that funeral pyre in 1949 is and will be the lingering light of the innumerable flickering chirags that brightens lives across India.