Re-reading Tagore in Chaotic Times

In 1942, a year after Tagore’s death, the war-torn Warsaw witnessed an unusual event- Janus Corsak staged Tagore’s play, Dak Ghar (The Post Office). This heart-rending play was enacted by the children of Auschwitz camp as they were awaiting their end in the gas chambers. It was a sort of preparation for their imminent death.

The line in the play, “Fear not, the fire will not touch you”, acted as the mystic spell ushering them into the profound calm of death; this possibility of a blend of the opposites, of the material and the immaterial, the worldly and the spiritual, death and immortality, resonates in Tagore’s life and works.

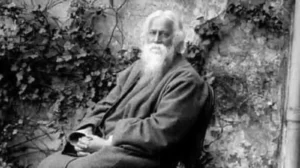

Rabindranath Tagore, our national poet demands a re-reading in these chaotic times when we are once again obsessed with the idea of the nation and its contours. It would seem his life was destined to be a composite of opposites: a lesson in the harmonious practice of living, of relationships, of language.

As a child, he grew up in a huge palatial home surrounded by luxury, but in the company of the servants of the house; he was born the youngest of 14 children, yet he had a lonely childhood; his parents were landlords, but they lived an ascetic life.

There are more such paradoxes (or perhaps it must be called a fluid blending). His ancestors were of the merchant class, Pirali Brahmins, but his home was flooded with artists and writers and scholars of all levels. He was trained in Vedic philosophy, but he did not hold Vedas as the only repository of knowledge. His popularizing the Baul Lalan Shahs songs, and his acknowledging the Bedouins’ earthly wisdom, is a way of thought, an episteme, essential to our times when sectarian politics reigns supreme.

Tagore’s creative experiments, a blend of mystical and physical, began at the age of eight and he published his poems at 16 under the pseudonym Bhanu Simha (Sun Lion). The fact that the critics mistook this work of this teenager poet to be long-lost classics of the ancients seems too consistent with the poet’s consciousness, where myth and reality operate, like his fluid destiny. His poetry was lyrical and mystical and lifted us up into sublime realms. However, his short stories were realistic and as he sensitively portrayed rural Bengal in meticulous detail in his prose, we are forced to confront the reality of a caste-ridden India. He was addressed as Gurudev and his sensitive and enlightened lines in the Gitanjali earned him the name the Bard of Bengal. But neither of these names define his amorphous person nor his well-defined thoughts.

In the year 1905, Calcutta was in turmoil and there were constant attempts to fuel communal tensions. In the Tagore household true to its tradition, women made Rakhis and tied them to Muslim men on Rakshabandan Day. The philosophy of Unity in Diversity was a practice that Tagore lived by. In his ‘The Religion of Man’, he says, we do not know how the elements as Carbon compose a piece of coal, all that we can say is that they build up those appearances through unity of inter-relationship, which unites them not merely in an individual piece of coal but in creative coordination with the entire physical universe.

Tagore’s mysticism is often mistaken for detachment from the real world and his privileged status is seen as an excuse to apoliticize him.

He was a mystic but he was also a doer.

When the Jalianwalah Bagh massacre happened, his was one of the intrepid responses. He renounced his knighthood as one would discard an ill-fitting garment and wrote an incisive letter to Lord Chelmsford. His prose was unequivocal, his vocabulary explicitly political, unlike his creative writings.

When he was sent to lord over the lands his family owned in Shelaidaha, he refused the ceremonial seat offered to the landlord and sat on the floor with them. He sat and walked among peasants and his short stories about rural Bengal, were an eyewitness record of their poverty and deprivation. Simone Weil, the French Philosopher and mystic, says, attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity. Tagore’s attention to the details of others’ lives does not have many parallels with the feudal world.

For Tagore, it was not an Us vs Them or Them Vs Us question. He denounced British Raj and advocated independence from Britain. Yet his refusal to think in binaries led him to criticise Gandhiji’s boycott of foreign goods. The Swadeshi Movement looted shops selling foreign clothes and made a bonfire of the goods thus depriving the merchants of their life’s earnings. Tagore used the trope of the machine to describe a nation-state. A nation in the sense of the political and economic union of a people is that aspect that a whole population assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose.

In the twenty-first century global space, national borders are permeable, and global finance controls globally irrespective of the political power of each nation-state. It is said that now political leaders can start a war, kill their own citizens, and render useless a whole community but when it comes to constructing a democratic structure and empowering people across the divide, the leaders are slaves to multinational corporations.

Hence the significance of Tagore’s concept of internationalism. When we are now reexamining the concept of Nationalism in a globalised world, Tagore’s ideas gain enormous significance. It is his ideas on nationalism that defines him. His nationalism embraced all other imagined communities and thus his vision of a university was a space that brought all humanity together. He was a humanist, universalist and internationalist who questioned the British ideals of nationalism and its excuses for a colonial rule: “thinking about the construction of Nation and civil society in the West, the Western powers were involved in creating colonies in the Global South” writes Homi Bhaba.

Tagore who wrote that Nationalism is a great menace and is the particular thing which for years has been at the bottom of India’s troubles was a seer who foresaw the State organising its powers against its citizens. Preservation is a goal of Nations at the expense of all those who do not belong to the Nation. Within the federal constitutional framework is a heterogeneity that is often ignored. According to Homi Bhaba, targetting people as outsiders is a part of the new tribal nationalist agenda to position majorities against minorities.

His idea of a space where the world makes a home in a single nest was realised in the world university that he built in Bolpur, West Bengal. He named it Visva Bharati.

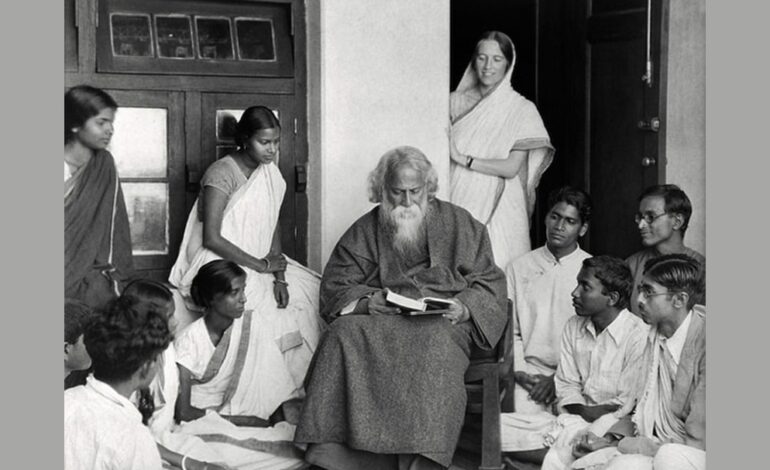

The closed spaces of classrooms of the colonial system were done away with and students learnt in natural spaces in the open shade of huge mango trees. Apart from providing a learning space which was freer and unrestricted, Santiniketan brought multifarious cultures around the globe into this rural setting.

Santiniketan was the ideal Nation where everyone lived in harmony irrespective of their ethnicity, culture, language, colour or gender.