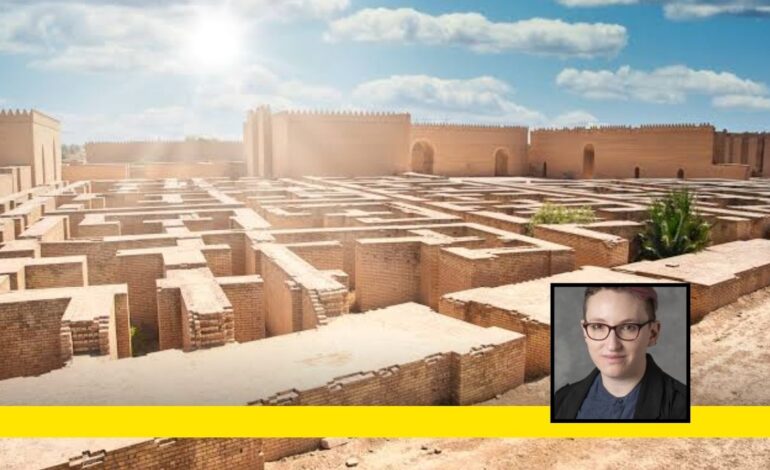

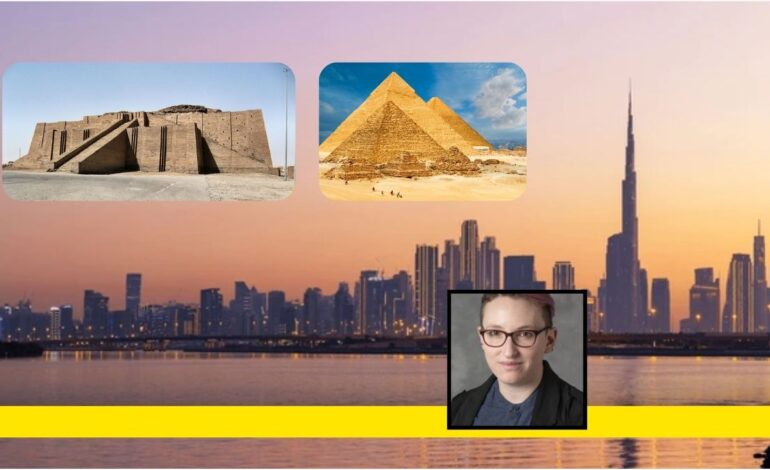

From towering ziggurats to sprawling urban grids, the legacy of ancient Mesopotamia continues to influence how we shape our cities today. This fascinating exploration takes you on a journey to the cradle of civilisation, where the first blueprints for modern urbanism were drawn. The article delves into how the ingenuity of the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians – through their architecture, urban planning, and societal organisation – laid the groundwork for the modern cityscape. This is a study that has special relevance to our times, when the continuity of this great civilisation is sought to be stamped out through reckless military assaults led by US imperialism.

Published in two parts, this series uncovers the story of Mesopotamia’s innovative urban culture and its profound influence on the present. The second part explore the intricate city planning, trade networks, and the symbolic legacy that Mesopotamian urban designs have left on global metropolises.

In the early 20th century, the Tower of Babel was frequently associated with the emerging skyscraper form. The reference had an ambiguous valence. It could express unease about the changing look of modern cities and anxieties about whether experimenting with non-traditional values (architectural or otherwise) was the first symptom of societal collapse on a biblical scale.

The Tower of Babel’s link with technological hubris dovetailed with associations regarding ancient sexual immorality, derived from Herodotus’ salacious reports of ritualised prostitution in Babylon and the New Testament figure of the “Whore of Babylon” in the Book of Revelation, where Babylon was a stand-in for the Roman Empire. In the late 19th century, it was low-rise London that was most often designated “Modern Babylon” after an 1885 series of articles published in the Pall Mall Gazette by its editor W. T. Stead exposed sexual trafficking in the city; the series was entitled, with reference to Herodotus, “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.”

The “babble” that the Tower of Babel triggered could also lend itself to associations with modern polyglot cosmopolitan spaces, which were both celebrated for their variety and damned for their dangerous racial ferment.

Yet as the skyscraper came to dominate the skylines of many American cities in the 1920s, designating a city a “modern Babylon” was increasingly meant primarily to invoke its architectural form. Absent from the connotations of sexual depravity or confusion of tongues, the association of skyscrapers with the never-bettered ancient tower was often merely a form of aggrandizement, a celebration of the technological wonders modernity could produce, coupled with perhaps a tinge of nostalgic hope that modern technology might facilitate a return to cooperation and human unity of purpose.

Hence: a 1908 article on the triumphant rebuilding of post-earthquake San Francisco as a record achievement for any “ancient or modern Babylon”; a 1923 article on the skylines of New York and ancient Babylon as “growing more alike every day,” in each case a “good advertisement” for urbanism; a 1924 article describing the University of Pittsburgh’s “Cathedral of Learning” skyscraper as a new Tower of Babel uniting all scattered tongues with “all the sciences and arts of the age of steel”; a 1929 review of the painter William S. Horton’s New York skyline scenes showing “a modern Babylon, as no Babylon ever was, burning in gold and luxurious color, a city rising far above its mere human inhabitants, and dreaming the long dreams of mingled past and future”; and a 1934 description of the Boulder Dam as “Modern Babylon,” representing “the application of all the newest knowledge engineering,” yet visually “reminiscent of long bygone days.”

Here, biblical associations were joined by classical Greek accounts expressing awe at Babylon’s magnificent monumental architecture, including the seemingly mythical Hanging Gardens, a watered and planted version of the ziggurat, and a canonical Wonder of the World.

The most famous mobilisation of Babylon for a vision of futurity was another, better-known, Metropolis of the 1920s: the German director Fritz Lang’s 1927 epic film. The design of its futuristic skyscraper city, home of a “new tower of Babel,” in which an underclass toiled in the bowels of factories and the rich played erotic games on rooftop gardens, was inspired by the skyline of New York. The film features a sequence in which its kindhearted, revolutionary heroine tells the biblical Tower of Babel story to a meeting of workers, rendering it as a parable about exploitation and injustice. The heroine’s evil double, most famous for her android form, appears in a dream sequence as the Whore of Babylon, in minimal clothing.

Lang’s various evocations of Babylon show that he was thinking of grandiose architecture, sexual immorality, and doomed tyrannical political powers all at once. But he was perhaps also thinking merely about what worked as a cinematic spectacle. At the time, Hollywood’s most famous depiction of ancient Babylon was D.W. Griffith’s 1916 mega hit Intolerance, which boasted massive, riotously adorned sets of the ancient city. This Orientalist extravaganza and other similar epics with biblical settings—like the Austrian Sodom und Gomorra (1922), which featured an enormous ziggurat—provided Lang with a suitably monumental cinematic vocabulary to invoke other worlds, whether long gone or yet to come.

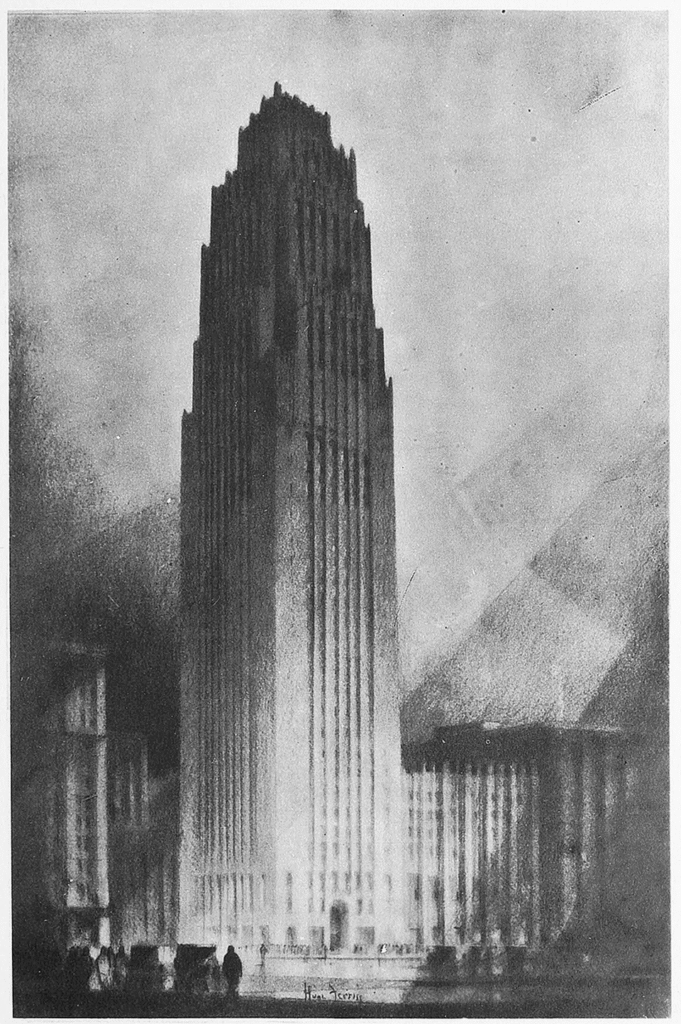

Ferriss and the Ziggurat Form

The ziggurat-skyscraper shape that Lang detected in the New York skyline was kindled by one regulation of outsized importance: the 1916 New York City zoning law that established maximum permissible massing for new buildings in the city. This law limited the total area of a lot that a building could occupy after a certain height, meaning that buildings would need to be “stepped back” as they rose, allowing sufficient light and air to reach surrounding structures.

The law effectively ended the possibility of simply building up in ever-higher boxes, a trend that had characterised skyscrapers before the law was passed. While the so-called “step-back skyscraper” emerged as a solution to a local piece of municipal legislation, the architectural historian Carol Willis has argued that, over the course of the 1920s, it would come to be understood by American critics and architects as the ultimate expression of a positive, and deliberate, aesthetic for American modernity. Outside of New York, other cities followed suit, and the step-back form became the paradigmatic shape of the skyscraper, as seen in the Empire State Building and Chrysler Building.

Ferriss was an evangelist for the forms encouraged by the 1916 zoning law. In 1922, he created a series of visualisations of step-backs in successive stages of abstraction. In Ferriss’ four-part sequence, the ziggurat, an ancient form, is revealed by this empirical, mathematical calculation of space as the answer for the future. Discussing this sequence of the “evolution of the step-back building” in Metropolis, Ferriss contrasts the pre-zoning Cube City with the post-zoning Pyramid City. A city of cubes is one in which each building “loses its essential identity,” whereas “no matter how closely pyramids are placed in rows, each preserves its essential individuality of form… which is essential to architectural dignity.”

No wonder, then, that in the whole of Metropolis, the ziggurat is the only ancient architectural form Ferriss evokes as a direct solution for the modern age: “The ancient Assyrian ziggurat, as a matter of fact, is an excellent embodiment of the modern New York legal restriction; may we not for a moment imagine an array of modern ziggurats, providing restaurants and theaters on their ascending levels?” Through Ferriss’s hand, the sacred architecture of ancient civilisations gets reimagined for the Jazz Age.

Ferriss’s interest in ziggurats likely had its origins in an act of imaginative reconstruction of a famous biblical structure with a better reputation than the Tower of Babel. In 1923 and 1924, the architect Harvey Wiley Corbett commissioned Ferriss to make a series of drawings for a reconstructed Temple of Solomon, the “First Temple,” destroyed by Babylonian troops in 585 BCE during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II. This was no mere exercise of historical speculation: The temple was to be erected as a temporary structure at the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Exposition, celebrating 150 years since the foundation of the U.S.

The mastermind of this project was John Wesley Kelchner, an eccentric New York native who spent his career pursuing reconstructions of Moses’ wilderness tabernacle and ultimately of Solomon’s Temple, styling himself as the leader of the “Temple Restoration Movement.” Kelchner ultimately wanted to reconstruct seven identical Temples of Solomon “as world symbols of universal peace—the physical embodiments of a plan of spiritual unity throughout the world.”

The Temple of Solomon is one of the most often reimagined ancient buildings, even more so than the Tower of Babel. A detailed description in 1 Kings 7 provided the raw material for these imaginings, and from the early 19th century, ideas about Solomon’s Temple increasingly reflected the European fascination with Egyptian architecture. After the excavation of Assyrian palaces in northern Iraq in the 1840s, the architecture of Mesopotamia was also drafted to provide an analog of the Israelite wonder.

The exterior form that Ferriss and Corbett imagined for the temple seemingly drew from archaeological reconstructions, as well as from the set design of Griffith’s Intolerance, with its hybrid of Assyrian, Persian, and modern “Oriental” references. Corbett explained that “in the final design there will be found the trace of every type of construction known at the time of King Solomon: influences of Assyria, Babylonia, and Egypt all blended into a magnificent and harmonious structure.” He promised that “when we have completed our work, you will behold exactly the spectacle that King Solomon gazed upon when he had finished his temple”—an extraordinary claim for the collapsing of the ancient into the modern.

Yet, despite much publicity around the Philadelphia plan, the donation of land by the city, and the creation of a company called Temples and Citadels Incorporated to fund the venture, the reconstruction was never financially or practically feasible. Ferriss’ drawings simultaneously depict scenes of the ancient Middle Eastern past and the (then) American future: the ziggurat Temple of Solomon, as it existed in antiquity, but also as it could have been reconstructed in Philadelphia for a fair celebrating the foundation of the U.S., yet never was.

Ferriss got something out of it, though: a drawing he could reuse for imagining the architecture of the future. The style and certain incidental details make it clear that Ferriss’s “Modern Ziggurats” drawing, featured in Metropolis of Tomorrow, must surely have once belonged to this sequence of renderings.

Ferriss’ Final Clue

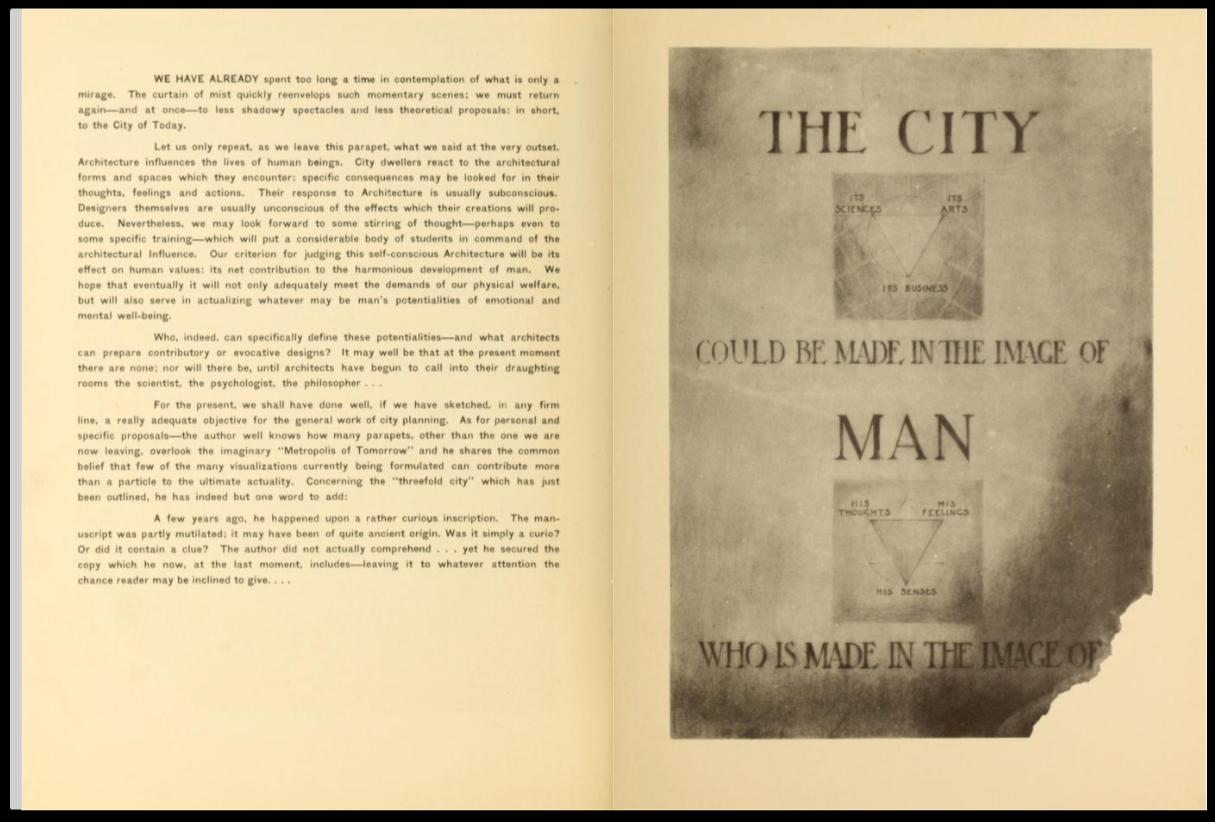

In the epilogue of Metropolis of Tomorrow, Ferriss reflects on the ideas he has presented and leaves us with one last image, a schematic city plan with a gnomic aphorism: “The CITY — ITS SCIENCES / ITS ARTS / ITS BUSINESS — could be made in the image of MAN — HIS THOUGHTS / HIS FEELINGS / HIS SENSES — who is made in the image of…” The sentence remains incomplete, its final words seemingly torn off the manuscript, but Ferriss proceeds to explain this image within a frame narration: “A few years ago, he [Ferriss, writing in third person] happened upon a rather curious inscription. The manuscript was partly mutilated; it may have been of quite ancient origin. Was it simply a curio? Or did it contain a clue? The author did not actually comprehend… yet he secured the copy which he now, at the last moment, includes—leaving it to whatever attention the chance reader may be inclined to give.”

This graphic and its apocryphal discovery are the most explicit evocation of an esoteric and mystical dimension that underlies all of Ferriss’ futurism. Though never a committed follower of any specific mystical path, he was, as Carol Willis puts it, drawn to “mystical philosophies which celebrated intuition and personal creativity and looked to geometry and harmonic proportions to discern universal laws.”

Ferriss traveled in circles enchanted by both Theosophism and the teachings of the Greek-Armenian mystic G.I. Gurdjieff. For Ferriss, as for many colleagues and friends in the modernist arts scene of 1920s New York, Machine Age aesthetics and their association with the rational complemented, rather than clashed with, an interest in a geometric mysticism that assigned psychological and spiritual significance to certain built forms.

When does the “discovery” of this piece of paper, this “clue,” take place? Is it “now,” in Ferriss’s present day, or in a faraway future walk-through of the Metropolis? The text doesn’t make it clear, but I think the latter. As such, the broken, “ancient” document probably could be dated to 1929, when Ferriss conceived this plan and dedicated it to the future builders who might realise his urban dream. It is fitting that his work ends with a confusion between past, present, and future, evoking a city of the future that, his text suggests, might have been planned at a time of “quite ancient origin.”

This article was originally published on Wiki Observatory and republished via NewsClick.