From Colonial Shadows to Mother Tongue…

…The Life and Times of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

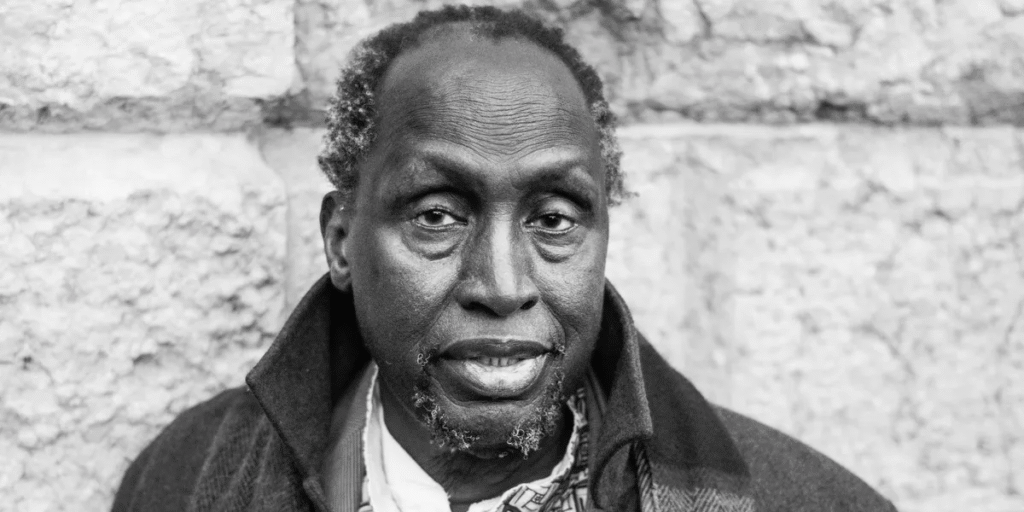

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, one of the most enduring figures in African literature, has passed away. His place in world literature deserves continued attention. His legacy rests on more than literary merit; it forms a bold political and cultural assertion. In a world where English remains a dominant literary force, his work disrupted established traditions and offered an alternative foundation for thinking about language, power, and belonging. His death coincides with renewed debates on the politics of language, particularly in the aftermath of Banu Mushtaq’s recent International Booker Prize win.

The question in recent conversations has revolved less around narrative technique or literary flair and more around the political stakes behind international recognition. Literary prizes now serve as battlegrounds for questions around translation, authenticity, and cultural autonomy. As vernacular languages gain visibility through such platforms, a deeper inquiry arises regarding the language writers choose to create in.

For those in plural democracies, writing in one’s language of intimacy appears as the natural choice. Yet for Ngũgĩ, fluent in both English and Gikuyu, the decision to leave English behind reflected a deep philosophical and political position.

He committed his literary future to Gikuyu, his mother tongue. Across essays and speeches, the same conviction is voiced again and again: writers from formerly colonized nations can reclaim dignity through their native languages. This shift arose from years of reflection shaped by personal history and collective struggle.

Born during British rule in Kenya, Ngũgĩ grew up in a village shaped by the pressures of colonial occupation and the aspirations of national freedom. His early world featured the sights and sounds of a country bracing itself for change, with freedom fighters and nationalist leaders shaping his sense of public life.

Ngũgĩ emerged from a peasant family, grounded in rural life and daily struggles. The quiet but unyielding influence of the women in his family etched deep impressions on his worldview. His mother, despite being illiterate, insisted he go to school. His stepsister, a natural storyteller, sowed in him the seeds of narrative wonder. These influences remained foundational to his craft and consciousness.

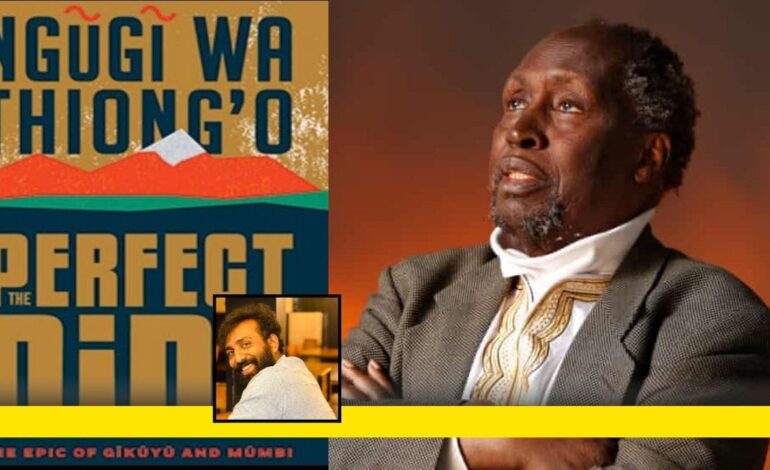

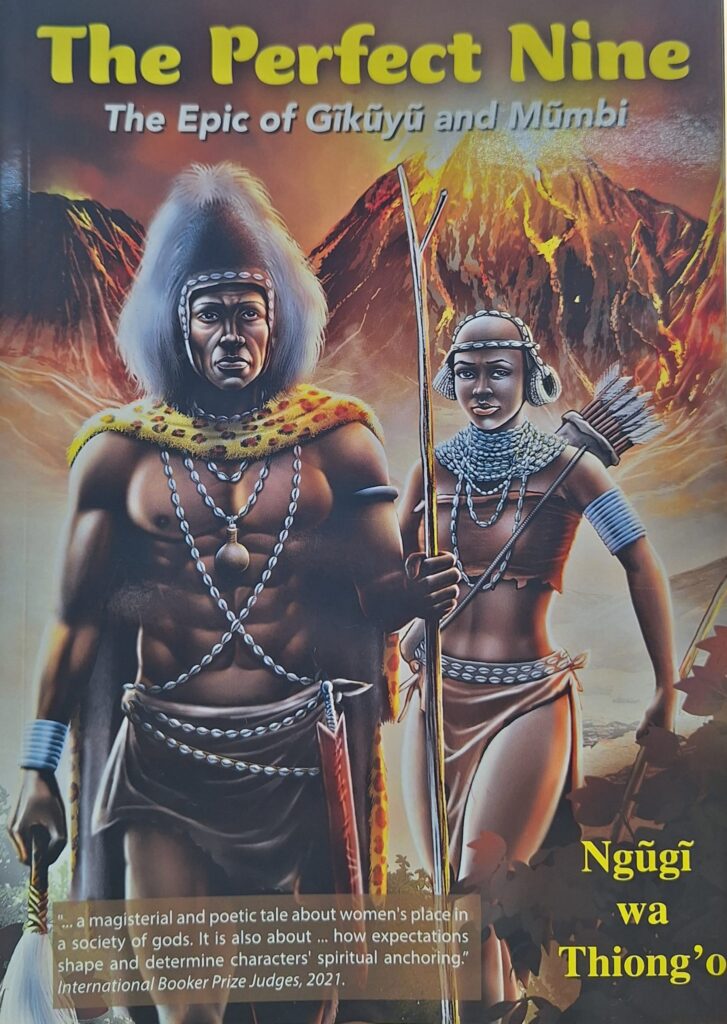

This formative influence found its way into his literature. In The Perfect Nine, Ngũgĩ reimagined the Gikuyu creation myth through a matriarchal lens—asserting a distinctly feminine narrative voice and repositioning women at the centre of cultural memory.

Ngũgĩ also located his anti-colonial consciousness within a wider global solidarity. As a young man, he would often see portraits of Gandhi in Indian-owned shops across Kenya. Elders spoke of India’s freedom, believing that Kenya would walk a similar path. Elders would point to them and say, “They gained their freedom through Gandhi in 1947. Ours will come with Kenyatta.” Ngũgĩ remembered with warmth the Indian delegates who championed Kenya’s fight for independence.

Early in his writing life, English became the medium of expression, a path shared by many African writers of his generation. The influence of Chinua Achebe loomed large. For much of the West, Achebe stood as the singular voice of African literature. Ngũgĩ carved space in that long shadow.

The post-independence Kenyan state offered little comfort. Authority continued to be questioned in his work. Plays and novels criticized the betrayal of ordinary people by the new ruling elite. In 1977, he was imprisoned for his dissent.

The period behind bars marked a turning point. Language itself came into focus as a site of domination and resistance. Confinement deepened his sense that colonial influence extended far beyond politics—into education, literature, and speech. Commitment to Gikuyu became absolute during this time.

Inside prison walls, The Devil on the Cross was written on scraps of toilet paper. A novel filled with satire, feminist insight, and political sharpness, it addressed imperialism, class exploitation, and patriarchy. Women no longer appeared as supporting figures but emerged as bearers of vision and defiance.

Ngũgĩ’s literary journey can be understood in two arcs: the years before and after prison. His shift away from English was an act of reclamation. For him, all languages held equal worth. Writing in Gikuyu was an assertion of cultural agency, not a denunciation of English.

When I asked him once about living a bilingual literary life, he said it was no different from an English writer writing in their own language. And rightly so. Yet Ngũgĩ was deeply aware of how literary academia continues to valorise English. He was concerned about linguistic marginalization across the world—including of Malayalam—and frequently spoke against what he called “linguistic genocide.” He pointed to examples like Hebrew, a once-revived language that today produces globally significant literature. One may recall his contemporary, Amos Oz, who also returned to writing in Hebrew.

Critics sometimes argue that Ngũgĩ’s writings are overly political or linguistically narrow. I disagree. The attention his essays and speeches receive is not because his fiction is weak, but because his political clarity is strong.

In today’s India, these questions carry urgent resonance. On one side, forces push for ‘One nation, One language,’ marginalizing linguistic plurality. On another front, AI tools and language models promote standardization that risks flattening linguistic nuance. What would The God of Small Things be without its Malayalam cadences and village inflections? Much of its spirit would fade.

Ngũgĩ’s insights offer essential guidance. Language now travels through algorithms, transcriptions, and global platforms. His vision urges writers and readers to stay rooted, even as the world rushes forward.

To remember him is to continue the work. Honouring his legacy involves writing with full trust in our languages. His life reminds us that the road to cultural freedom begins with the village, the school, the mother’s voice, and the first lullaby sung in one’s own tongue.

Excellently Written