Narivetta’s Male-Centric Lens: Sidelining C.K Janu’s Legacy in the Muthanga Struggle

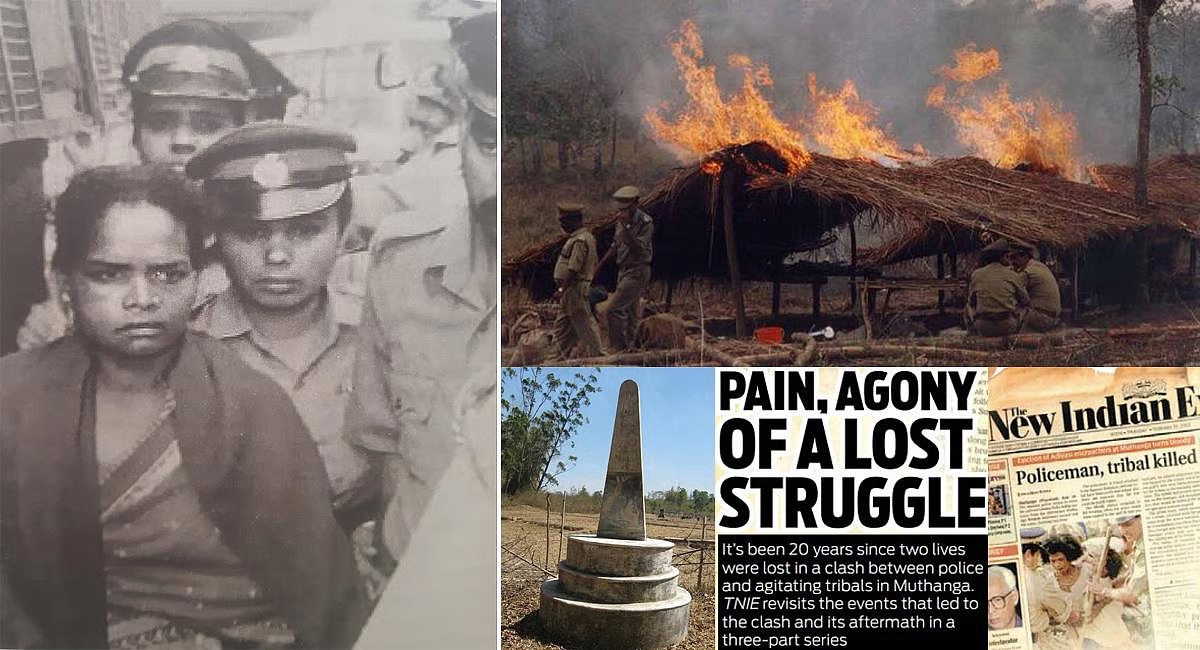

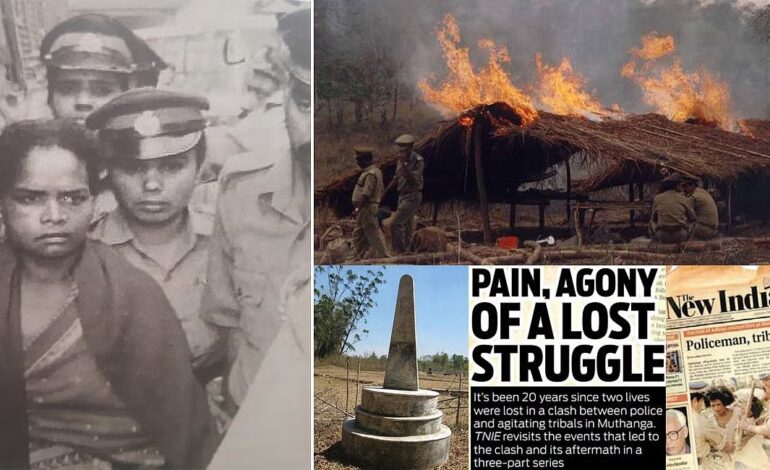

The 2025 Malayalam film Narivetta, directed by Anuraj Manohar and written by Abin Joseph, draws inspiration from the 2003 Muthanga incident, a pivotal moment in Kerala’s Adivasi land rights movement led by C.K. Janu and the Adivasi Gothra Maha Sabha (AGMS). This real-life uprising saw Adivasi families, under Janu’s leadership, occupy the Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary to demand land promised by the state. The state’s response—brutal police violence—exposed its role as an oppressive apparatus, targeting marginalized groups with inhuman tactics.

While Narivetta aims to dramatize this “dark chapter in Kerala’s history”, it falters by centering its narrative on Varghese Peter, a male police constable played by Tovino Thomas, while relegating C.K. Shanthi, a character inspired by C.K. Janu, to a marginal role. By making this narrative choice, the film weakens the portrayal of the Adivasi resistance and sidelines the leadership of a woman who mobilised her community against structural injustice. Drawing on Marxist theory and authentic references, this essay argues that Narivetta’s male-centric narrative overshadows Janu’s legacy, prioritizing a policeman’s moral awakening over the lived realities of the Adivasi women who drove the movement.

The Historical Context: C.K. Janu and the Muthanga Uprising

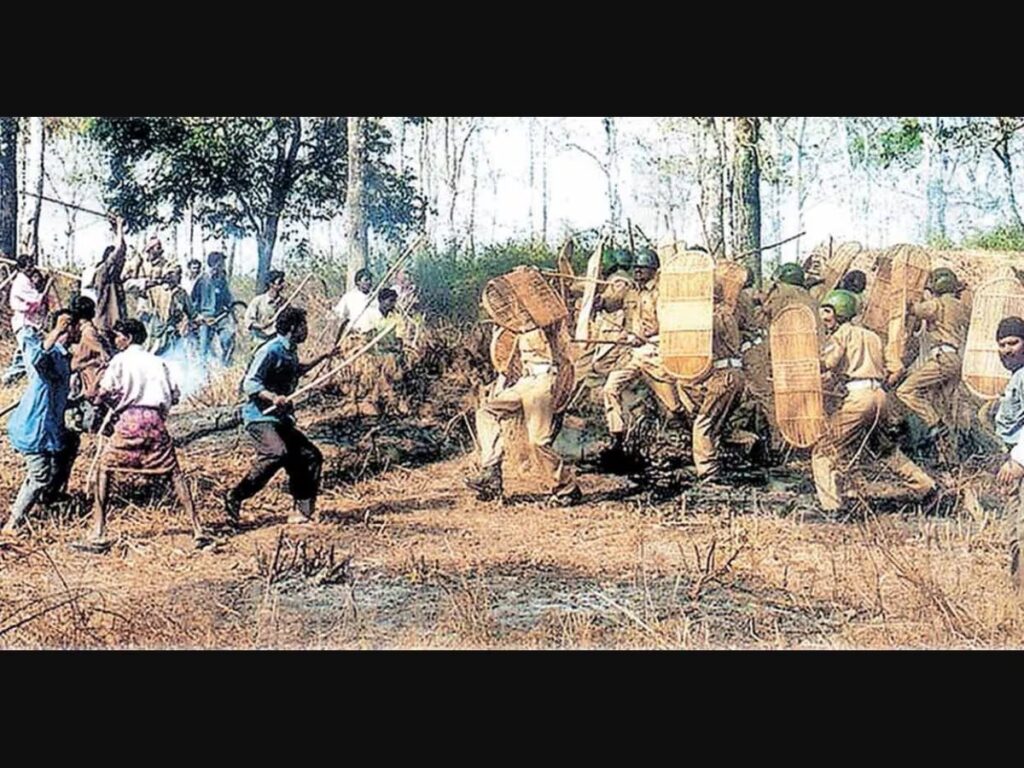

The Muthanga incident of February 19, 2003, was a turning point in Kerala’s Adivasi history. After decades of displacement and broken promises, the AGMS, led by C.K. Janu and M. Geethanandan, mobilized thousands of Adivasis to occupy the Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary in Wayanad, demanding land rights promised in 2001 after a 48-day protest in Thiruvananthapuram. The state responded with lethal force. Police and forest officials evicted protesters, resulting in at least two deaths—one Adivasi and one policeman—though accounts suggest higher tribal casualties. However, multiple eyewitness accounts suggest that tribal casualties were significantly higher. Janu’s autobiography, Adimasanthathiyude Adayalappeduthalukal (Recordings of a Slave’s Ward), details the custodial violence she endured, including physical and verbal abuse, alongside allegations of molestation and rape faced by other Adivasi women. State violence is deployed as humiliation, especially when gendered against women from oppressed communities.

These acts underscore the state’s role as a coercive instrument, as described by Lenin in The State and Revolution: “The state is a machine for maintaining the rule of one class over another”. The Adivasi revolt, led by Janu, exemplifies the oppressed rising against systemic exploitation, with her leadership as a woman from the Ravula (Adiya) community amplifying the intersectional struggle against caste, class, and gender oppression.

C.K. Janu, born into a landless tribal family, emerged as an “organic” leader, free of abstract political dogmas, funding her movement through grassroots solidarity. Her role was not merely symbolic; she articulated a political agenda, declaring, “Adivasis should unite… We should become a political power”. This aligns with Rosa Luxemburg’s view in The Mass Strike that revolutionary consciousness arises from the spontaneous struggles of the oppressed. Yet, Narivetta shifts focus from this female-led resistance to a male policeman’s perspective, a choice that critics argue “sidelin[es] the lived realities of the oppressed community it claims to honour”.

Narivetta’s Narrative Choice: The Male Policeman as Protagonist

Narivetta centers on Varghese Peter, a young, apolitical constable who joins the Armed Reserve Police Force under family pressure. His arc traces a transformation from ignorance to moral awakening, sparked by witnessing the state’s brutality against Adivasi protesters.

While Tovino Thomas’s performance lends “conviction and emotional weight” to this journey, the decision to frame the Muthanga-inspired conflict through Varghese’s gaze raises critical issues. Reviews note that Varghese is portrayed as “somewhat of a man-child,” initially dismissive of Adivasi struggles, as seen in his insensitive remark, “Ithippo ivanmark vendi nammal kaval kidakkuanallo” (Are we now guarding these people?). His mentor, Basheer (Suraj Venjaramoodu), counters with a smile, implying a policeman’s duty is to protect the public, but this exchange underscores Varghese’s detachment from the Adivasi cause.

There is a broader cinematic trend where stories of marginalized struggles are filtered through an outsider’s perspective, often a savior figure from a dominant group. As The News Minute critiques, “The camera is almost always placed outside the protesters’ fence, looking in from the point of view of the young and homesick Varghese”. This framing risks aestheticizing the Adivasi struggle, reducing protesters to a “background” rather than agents of resistance. Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, critiques such narratives for reinforcing ruling-class dominance by centering voices that align with state structures—like a policeman—over those of the subaltern. By prioritizing Varghese’s redemption, Narivetta inadvertently diminishes the revolutionary agency of the Adivasis, whose revolt embodies Marx’s assertion in The Communist Manifesto that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”.

The Marginalisation of a Female Leader

The character of C.K. Shanthi, played by Arya Salim and inspired by C.K. Janu, is a critical point of contention. Yet, she is reduced to brief appearances, with a character arc that remains thin and underdeveloped. Reviews praise Salim’s “fiery and commanding” performance, noting her ability to evoke Janu’s resolve, but the script fails to flesh out her character. As The South First observes, “The film stages the wound but does not allow the wounded to narrate their own history”. While Varghese is fleshed out with subplots—including a sentimental, unnecessary romantic track that consumes valuable screen time—Shanthi remains mostly static and symbolic.

This sidelining is particularly egregious given Janu’s real-life significance. Her autobiography recounts not only her leadership but also the gendered violence she faced, including custodial abuse aimed at breaking her spirit. Marxist feminist perspectives, such as those of Luxemburg, emphasize that women from oppressed classes play a dual role in resisting both capitalist and patriarchal structures. Janu’s leadership embodied this, yet Narivetta reduces her to a symbolic figure, with one review noting that “the true hero of this story, if told from the other perspective, only gets limited presence”. This choice reflects a broader failure to center the “political subjectivity of the oppressed,” as The South First critiques, reinforcing a liberal tendency to speak for the subaltern rather than amplifying their voices.

The film’s focus on Varghese also perpetuates a gendered narrative hierarchy. While Janu’s real-life struggle challenged the state’s patriarchal and class-based oppression, Narivetta elevates a male figure who, as a policeman, is complicit in that oppression until his late epiphany. This is similar to films like Nayattu, where systemic issues were explored through the lens of those within the system rather than the oppressed. By contrast, Tamil films like Vissaranai, Viduthalai, Jai Bhim and Karnan center marginalized voices, offering a more authentic portrayal of resistance. Narivetta’s failure to prioritize Shanthi undermines the Marxist principle that revolutions are driven by the oppressed, not by sympathetic outsiders.

The State’s Oppression and Marxist Resonance

The film does succeed in depicting the state’s oppressive machinery, aligning with Marxist views of the state as a tool of class domination. Scenes of police cutting off water supplies, using animalistic slurs, and unleashing lethal violence expose “the cold machinery of systemic cruelty”. These reflect the real Muthanga incident, where police actions led to deaths, injuries, and mass arrests, with no accountability for officers. Janu’s autobiography describes the state’s tactics—physical torture, psychological harassment, and gendered violence—as attempts to crush Adivasi resistance. This resonates with Marx’s view in On the Jewish Question that the state masks exploitative relations under the guise of law and order.

However, Narivetta’s focus on Varghese’s moral conflict dilutes this critique. What could have been a collective indictment of the state apparatus becomes a personal drama of ethical reckoning.

Authenticity and Missed Opportunities

Narivetta earns praise for its authentic portrayal of Adivasi dialects and culture, avoiding exoticization. Yet, its refusal to name Muthanga, Janu, or Geethanandan directly—while understandable for cinematic fictionalization—creates distance from historical reality. Reviews note that the film’s “meandering focus” and “rudimentary storytelling” prevent it from documenting the tribal land rights movement effectively. The choice to center Varghese, rather than Shanthi or other Adivasi characters, is seen as a deliberate but flawed decision, with The News Minute arguing it reduces the movement to “the heroic last act of the leading man”.

An alternative approach could have been drawn from Janu’s own words: “The agitations will end if all the landless people get land”. A narrative centered on Shanthi could have explored her personal and political evolution, mirroring Janu’s journey from a farm worker to a leader who challenged Kerala’s “progressive” image. The film’s dispersed focus and simplified storytelling prevent it from doing justice to the land rights movement it seeks to evoke.

As The Hindu notes, “This story needs to be told,” but Narivetta falls short by not letting the wounded narrate their own history. A truly Marxist lens would have centered Shanthi, embodying Janu’s legacy as a woman who defied the state’s inhumanity, and given voice to the Adivasi Gothra Maha Sabha’s fight for justice.