The Organic Muse

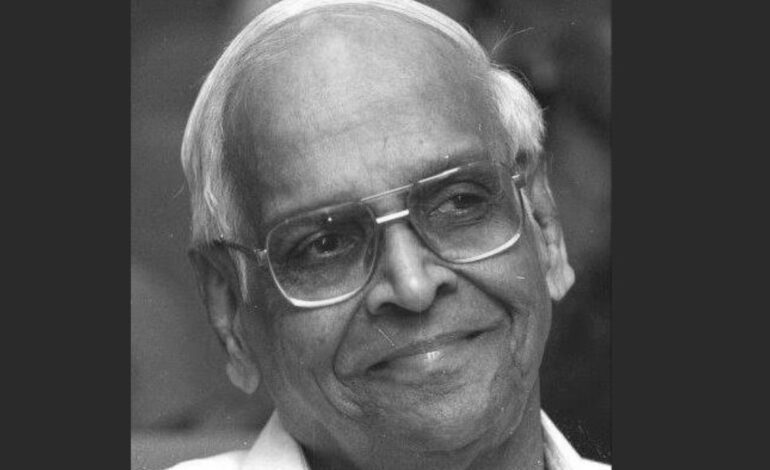

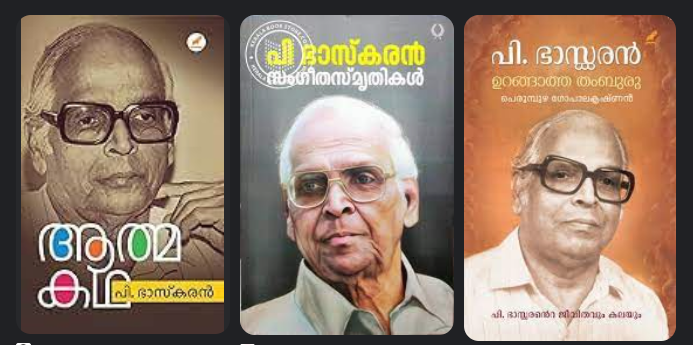

The birth centenary year of legendary Malayalam poet P Bhaskaran was celebrated in 2024 through several programmes including literary gatherings, seminars and art installations. Here, renowned journalist Sashi Kumar writes on the poet and his oeuvre, drawing from the special personal relationship he had with P. Bhaskaran.

This piece is a personal tribute to P. Bhaskaran from one who fortuitously became his son-in -law, but who had held him in awe and admiration for long before that. Rather, it is a tremulous attempt at a tribute by one who feels, even as he moves into this second sentence, unequal to the task.

I have asked myself umpteen times why it is that I find it so difficult to write about P.Bhaskaran. That there is nothing new or different I can say about one who is so, almost ubiquitously, remembered and cherished – in poem and song and cinema – by the Malayalee is certainly an obvious deterrent. But there is, alongside, the fear of inadequately expressing, because I have nowhere near his language and magic with words, the ineffable ways in which he has been, and is, part of my subconscious and my waking moments.

It was the 1950s and I must have been in the third standard at the Sacred Heart High School at Worli in what was then Bombay, where my father then worked and my family then lived, when I sang “Naazhiyoru Paalu kondu Naadaake Kalyanam…” solo on stage for an event organised by the local Malayalee Club. I don’t actually have any memory of it, but I clearly remember both a photo of me fully immersed in the song in the family album and my mother’s proud narrative around it to any visitor unwittingly chancing upon it. And for long afterwards, whenever the subject of music came up in any discussion at home my mother would slip in my Nazhiyoru Paalu achievement. Those opening lines of the song by Bhaskaran Mash for the watershed film ‘Neelakkuyil’ would translate as “With just a small measure of milk, marriages galore across the countryside…” Those looking for the inexorable connect of destiny could perhaps stretch the small measure of that song, delivered by a six or seven year old boy, a long way forward, across two decades and more, to when he was to marry the lyricist’s daughter.

My mother must have chosen that song for me because she liked it; certainly not because she had any supernatural intimation of her future daughter in law – more so because she was intuitively and instinctively atheistic and not likely to believe in such configurations of fate. I have not learnt Malayalam formally; at primary school the medium of instruction was English with Hindi and, while in Bombay Marathi additionally, as the second languages. But my mother determinedly taught me to read and write Malayalam at home, and I got to practice speaking it with colloquial nonchalance during the summer vacations I spent with passionate abandon mostly at my father’s ancestral home in Karuppadanna near Kodungalloor in Kerala. My childhood literary sensibility in Malayalam must have been shaped by a combination of the songs my mother constantly played at home and the avid consumption of Malayalam films during the said summer vacations in Kerala. And there must have been a liberal dose of songs by P. Bhaskaran in both. Little else can explain why I already knew by heart, even when I was in middle and high school (by then we had shifted to Chennai), a good bit of the lyrics and the entire tune, including the background score from start to finish, of so many of his songs. This then was my initiation into the world of Malayalam and simultaneously to that of P. Bhaskaran’s poetic imagination.

Years later when I, one memorable day, ran into his daughter at her college in Chennai where I had gone as part of a team from mine to participate in an intercollegiate festival, I had no inkling about her background or family, let alone that she was P. Bhaskaran’s daughter. This time round it did seem like uncanny serendipity that we should be thrown together, be drawn to each other, soon be engaged and, two or three years later, married.

Along the way I began exploring, with the zeal and deliberateness of a neophyte, the poetry of P.Bhaskaran, beginning with Vayalar Garjikkunnu and Orkkuka Vellapozhum. It was by no means a close, systematic or exhaustive study of his vast body of work. But as I read, the essential and enduring traits of his creative genius began to shine through, making me aware of another person inhabiting another world which none of us was privy to. I was drawn by the passionate humaneness, the heady sweep and swirl, of his mind and heart. I was fascinated by his intimate native grasp of the geography, the topography, the botanical cornucopia, the cultural arabesque, of Kerala. I was lured by the inimitable descriptive power and the instant metaphoric spin that came to him so effortlessly, that seemed ever at his beck and call. I was lulled by the lilt, the cadence, the rhythm of his words strung out in the soft glow of the moon, swaying gently in the light breeze which permeated them with the mild fragrances of wild flowers. I was awed by the way he invoked words to induce, then to caress, then again as a balm for, pain, emptiness, separation, longing in love. I was spellbound by the verve with which he marshalled words to raise the standard of revolt, to defy oppression, to assail injustice, to commemorate martyrdom, to foster comradeship and a purposive camaraderie. His corpus of poetry and repertoire of lyrics were as variegated as they were vast, a wondrous range of moods and states of mind – from mischievous tease, through ellipses of sighs and smiles, quotidian domestic vignettes, to philosophical, spiritual reflections on the larger questions of existence.

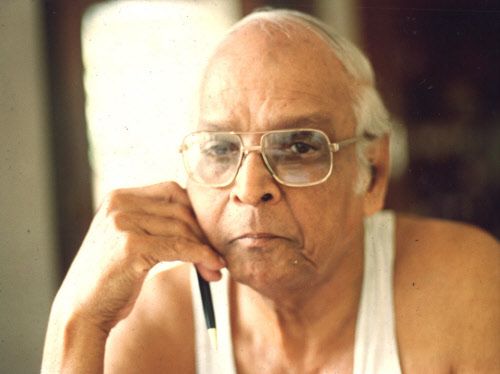

He wrote with such feeling and power with little fuss or, for all appearance, with little preparation. He would, the many times I have seen him at it, be sitting at his table letting the words flow from his pen onto a white sheet of paper, pausing occasionally to ascertain the fit of a metre by test-drumming on the table with his hands. Beat and rhythm, he often said, were everything in art and in life. But if he, his verse, became a part of the Malayalee subconscious, if the imagery, the sentiment, the profound abstractions and deep insights he evoked have become so pervasive and so enduring generation after generation, it was because he was the organic muse of his people. There was nothing cosmetic, artificial, intellectualized or forced in his language or creative imagination. It was rooted in his lived reality and bore the stamp of the earth he grew up on and was moulded by, of the sights and smells and sounds of his native environment nurtured in his heart, of the syncretic social and cultural mores of Kerala which he had internalized, and of the causes that moved and impelled him morally and ideologically. These traits, which were in good measure shared by, or nostalgized by, Malayalees, found a ready emotive resonance in their psyche. It would not be an exaggeration to say that his work, in turn, has, in ever so many little and subtle ways, reconstituted and reshaped the conscious and unconscious elements of that psyche.

His verse was his distilled being. Poetry and lyrics were really inseparable and interchangeable as categories in his creative process. It would seem that the pitch of a one stringed drone (Ottakkambiyulla Thamburu) traced his sensibility like a virtual aural note that moved ever ahead, stopping only where and when he finally ceased writing. Words flocked, at his behest, to take their places on this blank note, breathing life and meaning into it, in pitch perfect harmony. His moral compass set the direction of that note. His aesthetic impulse drove it forward. This singular note was not to be confused – not by him, not by us – with the political or party line that seemed expected of him as an early star-poet of the left. O.N.V. Kurup once told me how the first anthem of the communist party in Kerala written by the very young P. Bhaskaran, then a mysterious person known only by the pseudonym Ravi, had been a source of inspiration for him and numerous others to pursue their revolutionary paths. In later life he may have been privately critical of the dogmatism and structural ossification that had taken hold of the party. But he never abandoned the core convictions which drew him to communism in the first place. In the last few twilight years of his life, when his mind was not entirely in his control, and when the family despaired about his public appearances and interviews in the media (not being sure what might emerge, or be wrested, from his mouth in a confused state of mind), there was a defining moment in the course of a television appearance when the interviewer asked him how, looking back now, he felt about his earlier role as a revolutionary. His reply was instantaneous, “I feel proud about it”. That was straight from the heart, without a thought for political propriety.

Through his life, more often than not, his heart ruled his head. For one who had written all those hundreds of poems, their charged iconic lines chanted from public pulpits or in smaller groups or recited by selves in solitude; for one who had penned all those thousands of lyrics, most of them a ready hum on the lips of the Malayalee anywhere; for one who had directed and produced as many as fifty films, many of them trailblazers or milestones of an era of Malayalam cinema, he did not notch up a bank balance to match. For that matter, he did not have a head for finance. He was, if anything, perfectly content not to have one. Fuss about money, or worse, about the lack of it, irritated rather than unnerved him. One could say he had a healthy contempt for money other than its strictly utilitarian purpose of the moment. It was a disdain that put him in straitened circumstances, even pushed him into deep trouble. But he coped gamely with the lows of his life, reconfiguring the options before him, adapting to each changed circumstance like to a new beginning, starting from scratch with a new energy, a fresh outlook.

The equanimity with which he handled making and losing money, his affluent and difficult days, was edifying, although the family and those around him must have gone through anxious periods. Money was simply meant to be earned and spent, not to be accumulated, or diligently saved. It was always so, as one of his closest and longest-standing companions, (Shobana) Parameswaran Nair, was fond of recalling from the early days when the two of them, together with a couple of other close friends, were roughing it out in the then Madras. There would be times, he remembers, when there would be no money in hand for the next day’s expenses or to pay the rent for their modest lodge falling due in a few days. Bhaskaran-mash, he would proudly recall, was their savior, their “emergency ATM” as he put it, in such situations. They would scour the newspapers for ‘akshara shlokam’ competitions in Malayalam or Sanskrit, fairly common then, with decent prize money for the winner. Bhaskaran-mash would be goaded by them to participate and would invariably return with the money, staving off the crisis. He knew and could deploy Sanskrit to such ends, but studiously steered clear of it in his writing. In fact Sanskritised words figure very sparsely in his uniquely native and simple yet lustrous Malayalam lexicon.

He remained unchastened by Mammon to the very end. In his own self-recokning, he never felt he was any the poorer for lack of money. On the contrary, he was ever confident about his own resourcefulness, ever bullish about his creative capital. His life and his work proved him right. No amount of money could have earned anyone the warm cherished place he has earned for himself in the hearts of millions of his fellow Malayalees.

Shobana Parmeswaran Nair recounts an instance from their early filmmaking days when the two of them were stranded one late night on a road side in Wayanad and had to hitch a ride in a truck passing by. The truck driver kept singing the song “Kaayalarikathu Valyerinjappol Valakilukkiya Sundari..” (also from ‘Neelakkuyil’) through the night. When, towards dawn, the two of them were dropped off near their destination, Parameswaran Nair asked the truck driver why he kept singing that particular song throughout. He replied that it was his favourite song and that it kept him awake and alert and cheerful when driving at night. Paramewaran Nair then disclosed to the driver, to the man’s disbelief and amazement, that the one who wrote the song was his other passenger.

Towards his last years, with the onset of Alzheimers, it was as if he was anonymized to himself. He became a stranger to himself. On more than one occasion he would, on hearing a song written by him on the radio or TV, observe: That’s a beautiful song. I wonder who wrote it. The anecdote of S. Janaki, who had sung so many of his songs and for many of his films, visiting him at this time and returning heartbroken because he could not recognize her even though she tried singing for him to get him to remember, is by now familiar through circulation in the social media.

My own wrenching memory of that last stretch of oblivion is of the occasion when, in 2006, the first Symphony Lifetime Achievement Award was presented to him in Thiruvananthapuram by V.S.Achuthanandan. Among others present were O.N.V Kurup, singer Udayabhanu and my staunch friend and colleague from my Asianet days, Krishna Kumar, who had founded Symphony and the award. In his speech, V.S. Achuthanandan dwelt at length on how Bhaskaran mash’s revolutionary poetry had galvanized communist leaders and cadres alike. VS recalled how, during their days of imprisonment, he and other jail mates involved in the Punnapra Vayalar struggle would regularly and defiantly recite ‘Vayalar Garjikkunnu’. He proceeded, then and there, to deliver a good chunk of the poem flawlessly from memory. As this stirring recitation was enrapturing the audience, I could sense Bhaskaran mash, who was seated next to me on the dais, becoming restless and agitated. “Whose poem is that?” he kept asking me and looked at me uncomprehendingly when I told hm it was his. I had to place a firm palm on his arm to keep him from getting up. Not many present may have noticed the inner turmoil of the poet unable to recognize his own work or words and yet, possibly, having flashes of belonging. Thinking about it later, this episode, for me, gave a whole new meaning to Roland Barthe’s idea of The Death of the Author.

By the time I finished your last sentence , I found it hard to hold my tears…. And it pushed me to a struggle to locate an apt vocabulary to express what I felt ‘down the melody lane ‘ laid memories of this Master Lyricist and Genius poet you enkindled !!!

Sir, by having finally paid this tribute, it is very satisfying for you to fulfill an overdue from your part. And from my teenage days onwards, I can’t recollect a period where I am not an ardent fan of Bhaskaran Master. His book aptly titled ‘ as Nazhiyuripaalu’ ( an anthology of his lyrics ) is the most revisited book in my library. And I have – being lucky on two occasions – got a chance to meet him twice in 2005 ( First, at an award function on the premises of the Alakapuri Hotel in Calicut constituted by the Ramasramam Trust and secondly, a few months later when Bhaskaran Mash was fecilitated at a function by M. T Vasudevan Nair on his 84th birthday ). And after his passing year (2007), I have lost one more kept treasure from me… The most cherished autograph signed for me (in a notebook ) by the iconic poet! In retrospect, some of the most beautiful feelings are generated by great loses ….

Sir, you are one of the luckiest and the blessed… BECAUSE YOU ARE THE SON IN-LAW of my beloved Poet P Bhaskaran…. Thank you.