Ram Mandir Anniversary: A Wake-Up Call for India’s Socio-Cultural Fabric

Senior Journalist and author Nalin Verma’s fortnightly column in The AIDEM titled ‘Everything Under The Sun’ continues. This is the fourth article in the column.

“Har-e Rama Har-e Rama; Rama Rama Har-e Har-e

Har-e Krishna Har-e Krishna; Krishna Krishna Har-e Har-e”

This age-old rhyme in the local lingo(s) of the Hindi heartland is sung in chorus by villagers, accompanied by the dholak (a two-headed Indian drum) and jhaal (cymbals), in devotion to Lords Rama and Krishna. Small groups circle a decorated idol of Rama in a pandal, ( tent of sorts ) singing the rhyme in various ragas—a common and vibrant sight.

The origins of this practice are unclear, but it features prominently in celebrations such as childbirth, marriages, festivals and many other religious events. These gatherings, known as ashtajaam, involve villagers singing this rhyme in musical groups for eight spells spread over 24 hours, forming a key element of folklore across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and the national capital Delhi.

Other regional folklore traditions, in dialects like Awadhi, Braj, Bhojpuri, Magahi, Vajjika, and Angika, include ballads, plays in farm fields and orchards, and enactments of mythological stories like Rama-Ravana and Krishna-Kansa. The advent of Islam and the Bhakti-Sufi movements further diversified this cultural tapestry, incorporating Islamic heroes, bards, and musicians into these traditions.

Rama and Krishna are more than revered deities; they are integral to life’s milestones. Women sing sohars (birth songs) like “Dasrath ke chaar go lalanwa anganwa khel-e” at childbirth, while at death, they chant, “Ram naam satya hai” (Rama’s name is truth). Performances of Ramleela (associated with Rama) and Rasleela (with Krishna) merge ballads and drama, portraying these deities as human-like figures experiencing joy and sorrow.

It’s reductive to single out figures like Bismillah Khan or Vilayat Khan for their contributions to Indian music, as nearly every village in the region boasts its own artists and performers. Many Muslim boys have excelled in playing Rama and Krishna, while Hindu boys have portrayed Ravana and Kansa. Similarly, Hindu women have sung laments in honor of Islamic hero Hussein during Moharram, showcasing the region’s syncretic culture.

I recall my grandmother singing with neighborhood Muslim women during Moharram as they bid farewell to a tazia procession:

“De re daadi, lavang ke chhariya, main chaloon karbaal ko”

(“O Grandma! Give me a clove; I’m off to Karbala.”) In this song, Hussein asks his grandmother for a clove as a parting gift before leaving for battle.

This cultural harmony was not invented by saint-poets like Kabir, Dadu, Tukaram, Raidas, or Raskhan—it evolved naturally, reflecting Aristotle’s idea of humans as “social animals” seeking joy in community and coexistence. These poets merely observed and celebrated this unity in their works.

Damaging Syncretic India, Modi Style

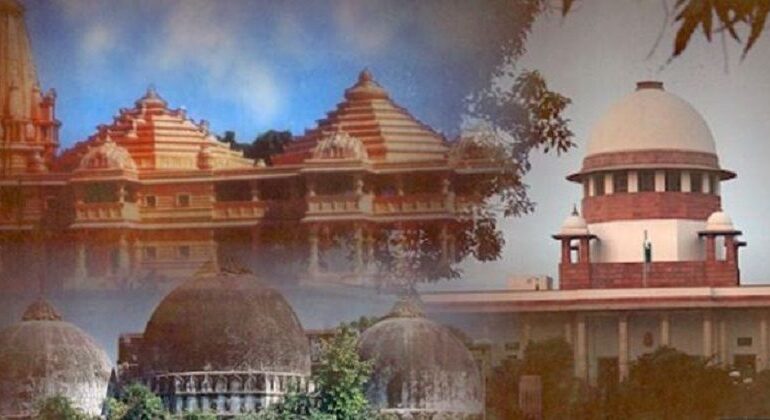

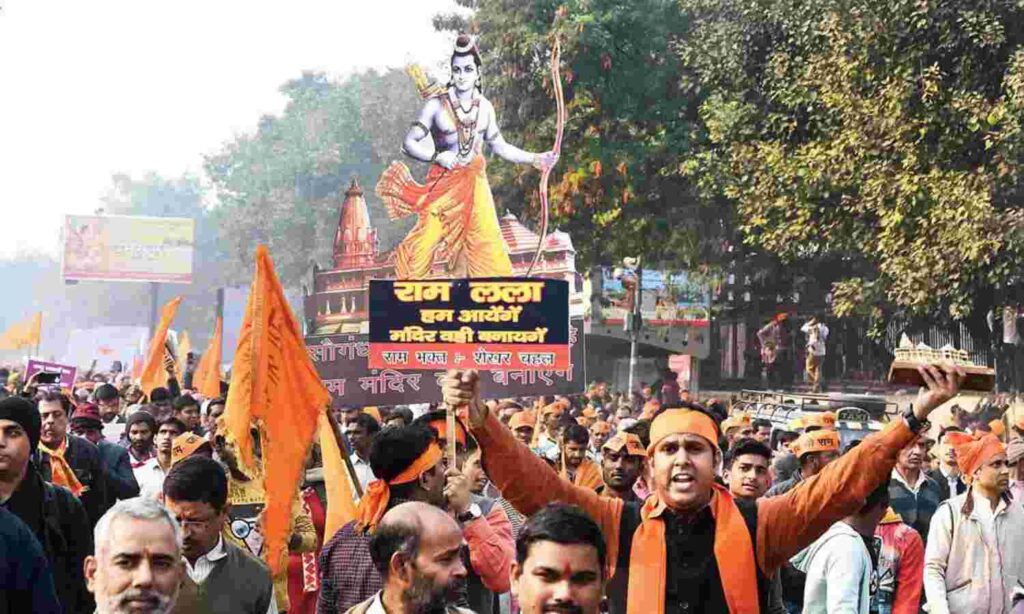

Over 32 years of the Sangh Parivar’s Ram Janmabhoomi movement, Hindutva zealots demolished the Babri mosque and spread anti-Muslim hate. With Narendra Modi’s BJP securing a majority in 2014, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has radicalized cadres, reinterpreting socio-cultural values to suit their agenda.

On January 22, 2024, Prime Minister Modi acted as jajman (religious patron) at the consecration ceremony of the newly built Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. By doing so, he flouted the Constitution’s mandate for secular governance, signaling approval of Hindutva’s divisive hate campaigns.

The Sangh Parivar’s radicalism has fractured the socio-religious fabric that sustained life for centuries. In this toxic ecosystem, An Abdul hesitates to play Rama in Ramleela, and a Ramchander fears singing “Tu hi Ram hai, tu hi Rahim hai” (You are both Ram and Rahim).

The BJP’s successive electoral wins since 2014, especially in populous states like Uttar Pradesh, have emboldened these zealots. Despite the destruction of the region’s syncretic mosaic, the BJP capitalized on its “success,” using it as a mandate to perpetuate their socio-religious agenda

2024 Elections: A Socio-Cultural Course Correction

Narendra Modi, who displayed his characteristic grandeur in gaudy attire during the consecration ceremony at Ayodhya on January 22, 2024, took a markedly subdued approach in January 2025, the first anniversary period of the new Ram temple. In the early run up to the consecration anniversary, it Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, sidelined at last year’s event, who performed the jalabhishek (ritual bathing of the deity), while Modi confined himself to posting wishes on his X handle.

Why the shift in demeanor?

The answer lies in the BJP’s performance in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, particularly in Uttar Pradesh—home to Ayodhya, Varanasi, and Mathura, the envisioned epicenters of the Sangh Parivar’s “Hindu Rashtra.”

The BJP was reduced to 33 seats in Uttar Pradesh, a devastating result for a party that had nurtured the Statez as its ideological stronghold. Even more jarring was the BJP’s loss in Faizabad-Ayodhya, the nucleus of the Sangh Parivar’s campaign to establish a political order rooted in Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s vision.

Narendra Modi himself faced a scare in Varanasi, trailing through four rounds of vote counting before retaining the seat with a sharply reduced margin. The loss of Faizabad-Ayodhya and the poor show in other constituencies were a rude awakening for the Sangh Parivar.

Some commentators sympathetic to the BJP have blamed electoral strategy. However, the fault lies deeper—in the very ideology of the Sangh Parivar.

In its euphoria over successive electoral wins, fueled by the imagery of an angry, bow-wielding Rama, the Sangh Parivar ignored the silent discontent brewing among ordinary people. They failed to hear the anguish of an Abdul stripped of his role as Rama in Ramleela, or the grief of a Ramchander denied the chance to play a hadra-hudri at a tazia procession. The Hindutva vandals shouting “Jai Shri Ram” on the streets missed the melodies of “Har-e Ram, Har-e Krishna” and “Sita Ram Sita Ram” that once united communities.

While media outlets beamed images of a confident Modi and his zealous supporters, they overlooked the growing yearning among ordinary people—peasants, potters, boatmen, barbers, cowherds, and shepherds—to reclaim a life steeped in harmony and shared traditions.

This simmering discontent found its voice in the BJP’s defeat in Ayodhya, Modi’s diminished victory margin in Varanasi, and the party’s overall decline in Uttar Pradesh. The people have begun a course correction, rejecting divisive rhetoric for the bonds of love and coexistence that once defined their lives. This course correction needs to be strengthened by all secular forces as the country gets ready to observe the first anniversary of the consecration of the Ayodhya Ram Mandir.

A wakeup call has always been there and the Indian soil has always been fertile to the idea of unity in diversity but it is yet to find a true leadership. Islamisation of Hindu Religion can be stopped only by strengthening the true hindu philosophy. It is a great fallacy to treat every anti BJP voice as a secular voice. It is self defeating.